Making Robots Perform Tricks: What Is China Hiding?

In the recently concluded Spring Festival Gala for the Year of the Snake, the most visually striking scene must have been the robots wearing floral-padded jackets and waving red handkerchiefs while performing a traditional Yangko dance.

At first glance, the robots, with their dark exteriors, seemed to lack the metallic sheen typically associated with high-tech aesthetics.

Their mechanical dance moves, accentuated by the floral-padded jackets, appeared absurdly incongruous and comical, making it easy to momentarily forget that these were state-of-the-art creations.

However, when the robots started spinning and tossing the handkerchiefs, flawlessly catching them mid-air, the audience was quickly brought back to reality, marveling at the complexity of their movements and the sophistication of the technology behind them.

These humanoid robots were produced by Unitree Robotics, and the models performing on the Spring Festival Gala stage reportedly cost 500,000 yuan each. Meanwhile, Unitree’s entry-level models are priced at 99,000 yuan, signaling that large-scale civilian use may not be far off.

Over the past two decades of rapid development in China, there has been a tendency to “a noble gentleman conceals himself within the vessel (A true gentleman does not ostentatiously display his abilities, just as a fine blade remains sheathed),” often leading to the perception of being “unsophisticated” .

As a result, until fairly recently, many people, both domestically and internationally, failed to realize just how advanced China’s technological and industrial capabilities had become. Ultimately, no matter how much one conceals, a tipping point of transformation is bound to arrive.

On the Japanese streaming site Niconico, where the Spring Festival Gala was broadcast, Japanese viewers commented that this performance was a demonstration of China’s technological and military strength.

Over the past month, a series of groundbreaking events—ranging from the unveiling of China’s sixth-generation fighter jet, the launch of the Type 076 amphibious assault ship, and the spontaneous comparison of living standards between Chinese and American netizens on Xiaohongshu, to the recent DeepSeek-triggered Nasdaq crash—have collectively hit like a whirlwind, signaling the true beginning of a new era.

China’s New 6th Generation

China’s New 6th Generation

Reaching this point has been no easy feat. If we say that China is now “no longer hiding,” it is not for any other reason than to confidently proclaim: we are a people who love peace.

The Chinese have not always loved peace—or, more accurately, in the classical era, true peace did not exist. The ancient agricultural empires of China had their boundaries, and beyond those boundaries, ancient China was always striving to construct a universal order, a concept fundamentally different from Europe’s.

In modern times, however, the national consciousness forged through the pain of foreign oppression, combined with the introduction of communism’s vision for saving the world, has embedded into the fabric of Chinese society a deep desire to resist oppression, to call for independence and self-determination, and to aspire for equality and peace.

Yet, the weight of the phrase “love peace” is immense. Those who control the existing order will not accept your declaration of peace—not because they think you are insincere, but because they deem you unqualified. To stop war with strength is not only ancient wisdom but also the direction shaped by the hard lessons that New China has learned along its journey.

Today, we can confidently tell the world: The Chinese invented gunpowder to make firecrackers and fireworks because we love peace. The Chinese built robots to perform Yangko dances and toss handkerchiefs on the Spring Festival Gala stage because we love peace. The Chinese use drone swarms for festive celebrations because we love peace.

Over the past month, the torrent of major events has pushed everyone and society as a whole to constantly update their understanding and reflect deeply. Since the pandemic era began five years ago, the entire world seems to have shifted into overdrive. For China, there is an urgency to transform and build a new order, to resolve the myriad contradictions accumulated during decades of rapid development, and to construct a new sense of shared identity.

This year’s Spring Festival Gala sent a clear signal by removing regional labels for performers from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Since the second decade of the 21st century, the Spring Festival Gala has increasingly evolved from a purely festive entertainment show into a platform with functional significance.

It has sought to strike a balance between the national and the local, the traditional and the modern, the ethnic and the popular, the mainland and the world. It has also positioned itself as the highest-standard stage globally, showcasing China’s image while reclaiming the right to define Chinese culture.

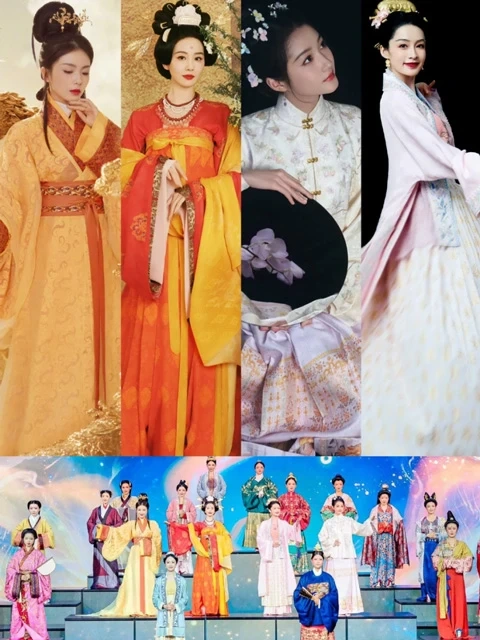

Last year’s Gala, with its simultaneous presentation of Hanfu styles from the Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties, alongside performances such as ‘30000 Miles from Chang’an’and the appearance of Hu De-fu from across the Taiwan Strait, conveyed a similar message. Today, China faces the task of further integrating its classical and revolutionary (Red) traditions, strengthening the fusion of a shared national consciousness, and achieving a unified sense of identity across the mainland, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

There are many problems to solve. Regardless of the approach, the development of productivity, technological capabilities, and military strength remains the fundamental prerequisite.

This year’s Spring Festival Gala can indeed be described as a showcase of industrial power. It was filled with a sense of cutting-edge technology and grandeur: the globally unmatched main stage, spectacular and breathtaking sub-venues, and new industrial icons like drone swarms, new energy vehicles, and robots replacing the older generation’s “Four New Inventions” such as high-speed rail. Together, these elements presented a thriving vitality distinctly different from today’s West.

At the same time, the portrayal of heroes from the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, PLA soldiers, workers, delivery drivers, and laborers from various industries underscored the foundational achievements of contemporary society.

In a developed industrial society, it is inevitable that some people contribute through construction and labor while others enjoy the fruits of their work. When the divide between production and consumption becomes too pronounced, people may forget the foundations of their society and lives, instead succumbing to various forms of selfishness that erode the social fabric.

For China, as a massive industrial society, avoiding the pitfalls of Western deindustrialization requires constant vigilance from both the leadership and the public.

It demands continuous efforts to maintain the foundations of the community and to ensure that the people who sustain society’s core receive ample rewards and recognition.

In the present, tensions between social classes, identities, and generations are undeniably complex. One of the fundamental challenges of the moment is to prevent people from becoming entirely lost in these conflicts and contradictions, thereby neglecting the maintenance of a shared sense of community and the foundations of society.

The Spring Festival Gala can avoid sensitive social topics, but real life cannot. Indeed, we are faced with an overwhelming number of issues, and these issues ultimately converge into questions about the path and model of social development. The major events of the past month have not merely given us moments to vent grievances or feel proud; they have also instilled a sense of urgency.

The successful flight of the sixth-generation fighter jet signifies the collapse of Western military coercion outside of nuclear threats.

The spontaneous comparison of living standards between Chinese and American netizens on Xiaohongshu has completely exposed the facade of the neoliberal financial empire. DeepSeek’s impact has announced the failure of America’s attempt at technological dominance.

At last, we can exclude all the voices tempting us to bow to the West and instead focus on discussing our own issues.

After the release of DeepSeek R1, Feng Ji, the creator of Black Myth: Wukong, posted on social media: “This is a technology breakthrough of national significance—a solid step toward the equalization of knowledge and information.”

And indeed, R1 has stunned the world by achieving GPT O1’s performance at just one-twentieth of the cost, shaking Nasdaq to its core. This remarkable model, being open-sourced and free for public use, not only allows everyone to enjoy the convenience of AI but also poses fundamental questions about the direction of our society’s progress.

It is well-known that the first two Industrial Revolutions not only advanced productivity and technology but also brought about massive transformations in social structures.

The Third Technological Revolution, rooted in the information revolution, has seen most established powers falter. Many have begun deindustrializing, with the information revolution decoupling from productivity.

Others have only achieved superficial applications of the information revolution while rejecting deeper structural changes to society. Still others, fundamentally lacking control over the revolution, have seen the U.S. dictate the limits of their progress.

As a result, most capitalist countries outside the U.S. remain confined to the productivity ceiling of the Second Industrial Revolution. Germany, reduced to “Industry 0.4” instead of “Industry 4.0”; old Europe, largely disconnected from the internet and AI; and Japan, clinging desperately to its outdated automobile industry while missing the mark on emerging technologies, all serve as real-world examples of this stagnation.

If China were to remain within the boundaries of the Second Industrial Revolution, it would never have the chance to catch up with or surpass the United States. But by choosing in the 1990s to fully embrace the Third Revolution, China has embarked on a path of profound societal transformation. On the heels of achieving basic urbanization, the nation now faces an even deeper wave of social upheaval.

Unlike Europe and Japan, China has never hesitated in this endeavor. On one hand, the state-owned economy has laid the groundwork with comprehensive infrastructure, the wide dissemination of technology at low costs, and equitable public services.

On the other hand, the market economy has propelled China from capital scarcity to capital abundance. Together, these forces have ensured the leapfrog development of the information revolution. From implementing VIE structures to fostering domestic internet giants, from innovations like shared bikes and ride-hailing services to the rapid advancement of AI technologies, China has consistently embraced and experimented with new economic models.

Of course, rapid transformation comes at a tremendous cost. Every Chinese citizen who has attended political science classes understands that qualitative changes in productivity must be accompanied by changes in production relations and societal structures. Since the dawn of the internet era, China’s social structure has undergone profound reshaping over the past two decades.

Yet, in the face of the knowledge and information equality that AI promises to bring, this reshaping is merely the beginning.

What does true knowledge and information equality mean? A brief extrapolation reveals that this “national-level” technological breakthrough is far from being purely good fortune—it is a sharp double-edged sword.

It implies that the spontaneous division of labor based on education, specialization, learning, and labor capabilities, the market-based primary distribution mechanisms, and the social production structures led by countless enterprises will all face fundamental reconstruction.

Society as a whole will either move toward a true cyberpunk future or embrace a deeper collectivism and socialism.

For a long time, the relationship between productivity and social relations, between the economic base and the superstructure, has been lost in confusion. This is not to say that productivity dictates everything, but rather that a qualitative leap in productivity forms the practical foundation for a new societal paradigm.

How does one achieve such a leap? It requires a correct trajectory in the preceding stages of development. The West has already proven that high technology does not necessarily translate into enhanced productivity—in fact, it can lead to its degradation.

Through decades of unwavering effort, the Chinese people have finally approached the singularity of qualitative transformation. We have avoided the wrong paths. But once we reach the singularity, we must confront even more revolutionary challenges. Whether we embrace or resist, this process will not stop.

In today’s world, no country’s people, as broadly or intensely as the Chinese, are calling for the arrival of a new system of production and economic relations.

What we do know for certain is that it is the unyielding efforts of our nation and people over decades that have brought about this storm-like transformation. And we will not hesitate or regret it.

How magnificent and romantic this endeavor is. Just as we invented gunpowder to make fireworks and firecrackers, just as we created robots to perform Yangko dances and toss handkerchiefs on the Spring Festival Gala stage, just as we use new energy vehicles for light shows, and just as we employ drone swarms for festive celebrations.

We defend peace with steel-like resolve and romance, and we will meet the tests of history through great practices.

Editor: huyueyue