How May China Help the World Break Free From US Tech Giants?

The successive releases of the DeepSeek-R1 and Grok3 models have sparked a new wave of global interest in large language models (LLM) artificial intelligence. DeepSeek has managed to train models that perform close to, or in some cases even surpass, OpenAI’s GPT-4, but at a significantly lower cost. Additionally, by leveraging “distillation” technology, DeepSeek has developed a series of derivative models with relatively smaller parameter sizes, minimal performance degradation, and practical utility. Examples include the Qwen-7B and Qwen-32B models, which have been deployed on the Chinese SuperComputing Network SCNet and are freely available to the public.

Based on my experiments and estimates, deploying and running the DeepSeek-R1 671B model (commonly referred to as the “full-capacity model”) for internal research and experimentation incurs an approximate cost of over ¥300 ($41) per hour or more than ¥100,000 ($14,000) per month. If supervised fine-tuning (SFT) is applied to the model, the cost could increase several fold. While this expense may be beyond the reach of most individuals and small businesses, it is well within the budget of large enterprises and national entities. In comparison, the visible costs of training Elon Musk’s so-called most advanced large language model, Grok-3, include the use of 200,000 H100 high-performance GPUs and an annual electricity consumption equivalent to nearly 200,000 U.S. households. Despite these staggering investments, Grok-3’s performance scores in model benchmarks are only marginally higher than DeepSeek-R1’s—by less than 100 points.

The Supercomputing Centre of Huawei

The Supercomputing Centre of Huawei

This signifies that large language models have been significantly “democratized” by DeepSeek: any country can now train and deploy an AI model that is largely autonomous, aligned with its own values, and tailored to its specific realities—achieving performance close to or at the world’s most advanced level. Just a few months ago, this was a feat only within the reach of the United States and China.

Governments of several countries have already recognized the significance of this transformation. The Indian government has announced plans to invest in “computing infrastructure, data, and capital support to build AI-related applications in fields such as agriculture and climate change.” It is reported that India’s large language model will be developed based on DeepSeek-R1. Meanwhile, South Korea has declared its intention to accelerate the construction of national AI computing infrastructure, aiming to become the “world’s third-largest AI powerhouse.” This goal, proposed by the South Korean government in 2023, clearly reflects an awareness that nations can now build their own “sovereign AI” in the near term, a process significantly accelerated by DeepSeek’s open-source initiatives.

Sergio Amadeu, a professor at Brazil’s UFABC University and former director of the National Institute of Information Technology (ITI) under the Brazilian Presidency, highlights that DeepSeek’s open-source initiatives “enable countries that have been technologically dependent on the United States to formulate strategies that favor their own development… democratizing [large language model] technology and opening new possibilities for nations in the Global South.” However, he also cautions that “open-source alone cannot address the challenge of building sovereign infrastructure critical to local and national development.”

Amadeu’s insight underscores a significant issue in the realm of digital sovereignty: it is a systemic endeavor that cannot be achieved solely through a single piece of legislation or the breakthrough of a “killer app.”

Influenced by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), discussions on digital sovereignty often center on the issue of data ownership—specifically, a nation’s right to use and manage data generated within its borders and to prevent its misuse by other countries. Corresponding solutions typically involve legislative measures to regulate local data storage and cross-border data transfers. For example, data generated within a country should be stored domestically, and any cross-border data transfers must comply with local laws.

Other researchers approach the issue from a communication studies perspective, focusing on the monopolization of information by U.S. internet giants and its subsequent impact on politics and national security. In response, they advocate for alternative internet platforms that operate independently of these major U.S. corporations. Concepts such as open-source development and decentralization are frequently highlighted in these proposals.

However, it turns out that data ownership is only one aspect of digital sovereignty, and to a large extent, it is a later-stage outcome rather than the root cause of a nation’s control over its digital future. The European Union realized this after implementing the GDPR for several years. Despite its strict regulations on data ownership, the reality remains that digital infrastructure—such as chips, servers, operating systems, and cloud platforms—is dominated by major U.S. corporations.

As a result, the EU has been left repeatedly investigating and penalizing U.S. tech giants for monopolistic behavior, yet it has been unable to stop the continuous one-way flow of data into the U.S., where agencies like the CIA and NSA maintain comprehensive surveillance. Recognizing this fundamental issue, the EU has begun developing Gaia-X, a cloud computing platform designed to compete with AWS. Of course, whether this initiative will achieve its intended goals remains an open question.

The Digital Sovereignty Index (DSI) framework argues that independent control over data ownership is the most visible manifestation of a nation’s overall digital sovereignty. However, without independence in digital infrastructure—the hardware and software that sustain digital ecosystems—restrictions on data ownership cannot be effectively enforced, as seen in the cases of the EU and Brazil. Similarly, without independent digital governance, the rules governing cyberspace will inevitably be dictated by U.S. tech giants.

Both digital infrastructure and digital governance independence rely on the capabilities of research institutions, enterprises, and talent engaged in the digital industry. Together, the four dimensions of digital sovereignty—independent control over data ownership, digital infrastructure, digital governance, and digital capabilities—form the complete framework of national digital sovereignty.

Because digital sovereignty is such a vast and complex system, attempting to reclaim it from U.S. digital hegemony solely through legislation on data ownership or by developing one or two “killer apps” is nothing more than an illusion. This reality also poses a significant challenge to the widely accepted “multi-stakeholder” theory in digital sovereignty research.

According to this theory, beyond the state, corporations, communities, and even individuals are also stakeholders in digital sovereignty. Their interests do not necessarily align with those of the state, and all should be given equal consideration in discussions on digital sovereignty.

A closer look at the four dimensions of the Digital Sovereignty Index makes it clear that building digital infrastructure, digital governance, and digital capabilities goes beyond the capacity of any individual or community. Only sovereign states or mega-corporations have the resources to undertake such foundational work.

Given that a handful of U.S. tech giants—closely aligned with the U.S. government—dominate most of the global digital space (with the exception of China), emphasizing a “multi-stakeholder” approach in the Global South often has the unintended effect of diverting attention away from national digital sovereignty. In practice, this weakens, or even undermines, efforts to strengthen state control over digital sovereignty, thereby indirectly sustaining U.S. digital hegemony.

In the field of large language model AI, DeepSeek’s open-source approach has prompted many Global South countries to consider a previously unimaginable aspect of digital sovereignty: sovereign AI. As large language models become increasingly central to how people access and generate information, control over these models effectively translates into control over ideology and value systems.

If Global South countries do not independently train and operate their own sovereign AI, their citizens will inevitably rely on AI products provided by OpenAI or other major U.S. corporations. This dependence means that these countries will have to continuously pay U.S. tech giants, their data will keep flowing into the hands of these companies, and they will have no recourse against the ideological biases embedded in these AI systems.

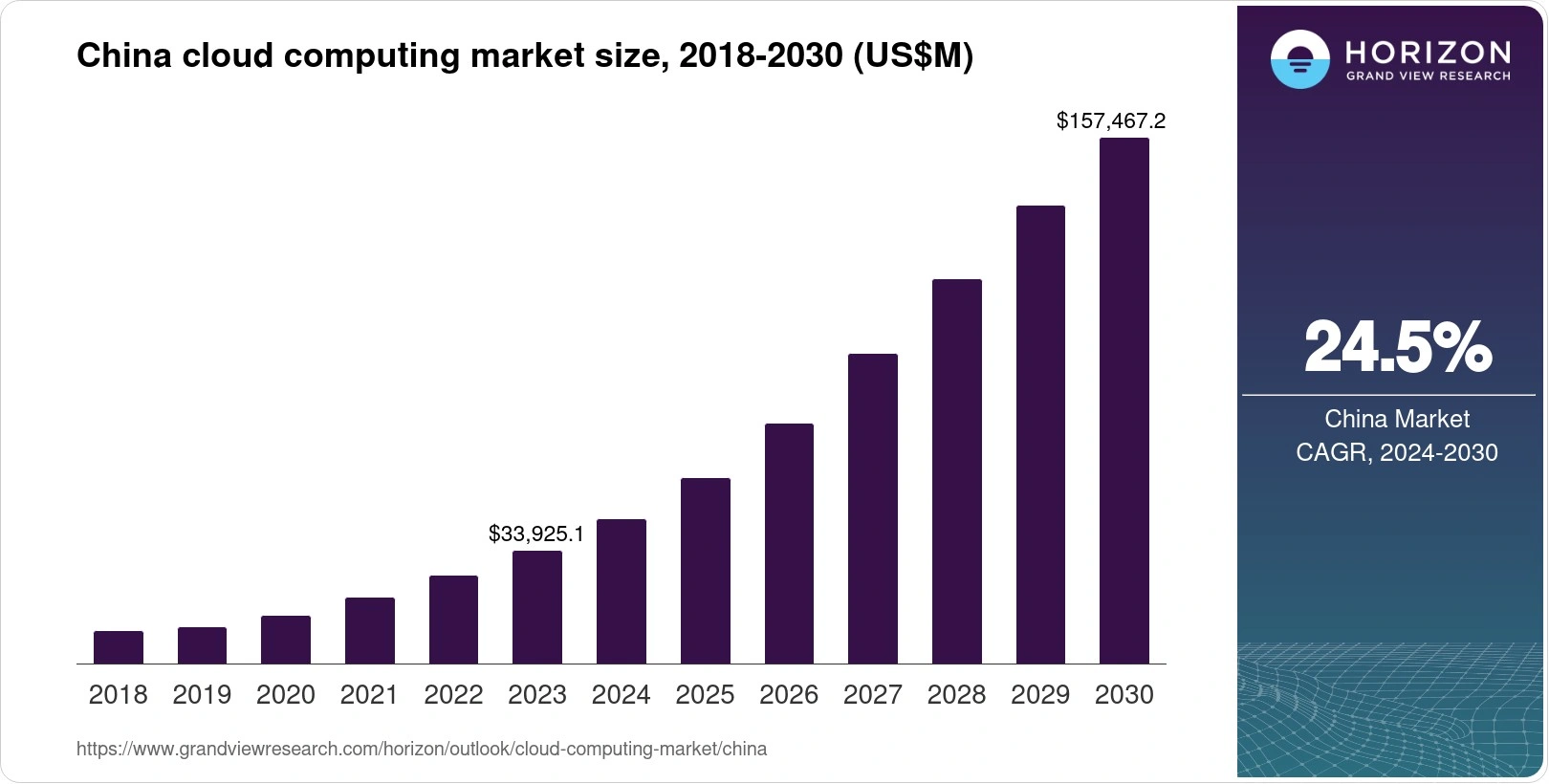

But as Amadeu has pointed out, once Global South countries—including relatively advanced economies like Brazil—begin developing their own sovereign AI, they will soon face broader digital sovereignty challenges. For instance, most Global South nations looking to train and deploy their sovereign AI models based on DeepSeek’s open-source framework currently have limited choices—they are likely to rely on cloud services from AWS or Azure. If the U.S. decides to ban its companies from providing services related to DeepSeek, these countries’ sovereign AI initiatives would be severely hindered. This highlights the constraints imposed by a lack of independent digital infrastructure.

For most Global South countries, building a relatively independent digital infrastructure and digital capability system is already a daunting challenge given their current scientific, industrial, and educational foundations. Even for a major economy like Brazil, digital infrastructure remains heavily dependent on the United States.

Since the policy shifts of the 1990s, Brazil’s ability to sustain long-term growth in its digital industry has been undermined, which is a key reason for its current low level of digital sovereignty. The situation is even worse for most other Global South nations, where reliance on foreign digital infrastructure is even more pronounced.

For most Global South countries, building a relatively independent digital infrastructure and digital capability system is already a daunting challenge given their current scientific, industrial, and educational foundations. Even for a major economy like Brazil, digital infrastructure remains heavily dependent on the United States.

Since the policy shifts of the 1990s, Brazil’s ability to sustain long-term growth in its digital industry has been undermined, which is a key reason for its current low level of digital sovereignty. The situation is even worse for most other Global South nations, where reliance on foreign digital infrastructure is even more pronounced.

How can Global South countries break free from U.S. digital hegemony and achieve a relatively independent digital sovereignty? Could cooperation with China help accelerate this process? These are pressing challenges that governments must now confront.

This year (2025), Brazil holds the presidency of the BRICS nations, and one of its six “priority work agendas” includes “encouraging inclusive and responsible AI governance to promote development.” At the time Brazil proposed this agenda, DeepSeek-R1 had not yet been released, and the concept of “sovereign AI” still seemed out of reach for the vast majority of Global South countries.

Now, with the open-source release of DeepSeek-R1 and the growing activity around its related open-source projects, countries like Brazil and other BRICS members may need to fundamentally shift their perspective on AI governance. The focus could move from relying on U.S. companies to provide AI solutions to exploring the possibilities of sovereign AI and multilateral AI governance.

With the BRICS summit scheduled to take place in Brazil this July, it will be crucial to see how the BRICS nations assess the changes DeepSeek brings to the global landscape. Whether sovereign AI, and digital sovereignty in a broader sense, will become a clear demand for BRICS countries will be a key point of interest during this year’s summit.

Given the democratization of large language model (LLM) artificial intelligence driven by DeepSeek, I recommend that countries in the Global South, such as Brazil, take immediate action to gradually develop their own sovereign AI and digital sovereignty strategies. Here’s a proposed roadmap:

1.Establish dedicated teams to study DeepSeek’s technology, focusing on understanding how to enhance or fine-tune the performance of large models in specific domains or topics through post-training methods. Additionally, explore how to develop complementary software (e.g., chatbots, intelligent agents) tailored around these models. This research should culminate in actionable plans for deploying autonomous and controllable sovereign AI systems.

2.Leverage the iterative development of sovereign AI as a driving force to identify and prioritize the importance of all data generated within the nation’s digital space. For the most critical data, establish clear ownership and control mechanisms. This can be achieved through legislation and enforcement to ensure that such data is stored domestically and that cross-border transfers of important data are strictly regulated.

3.Wile securing data ownership, strengthen collaboration with Huawei and other Chinese ICT enterprises to gradually reduce reliance on U.S. tech giants. This will help enhance national control over digital infrastructure and increase self-sufficiency in critical technological domains.

4.Collaborate with China within the BRICS framework to promote a multilateral approach to AI governance. This initiative should emphasize respect for national sovereignty while encouraging open exchanges of technology and expertise. The goal is to foster an international environment where countries can engage in equitable, mutually beneficial cooperation and consultation in the field of AI.

Editor: Chang Zhangjin

Anonymous

very good.