China’s Mars Rover Reveals Clues to a Lost Martian Ocean

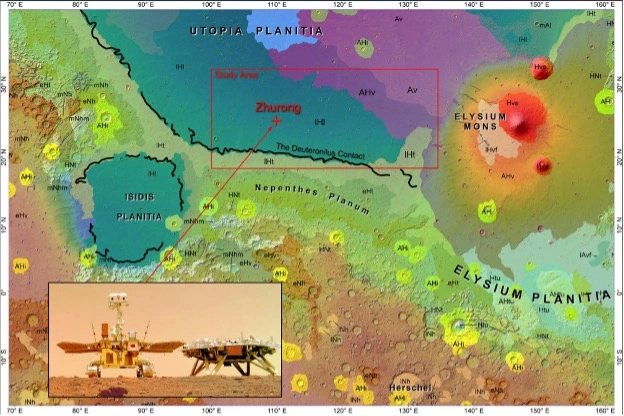

The quest to understand Mars’ watery past has captivated scientists for decades. Images of what appeared to be dried-up riverbeds and lakebeds hinted at a warmer, wetter Mars billions of years ago, fueling speculation about a vast ocean covering much of the northern lowlands. Now, a new study, based on data from China’s Zhurong rover and orbital observations, provides compelling evidence for this long-held hypothesis, revealing the remnants of an ancient nearshore zone in Utopia Planitia.

This groundbreaking discovery, published in Scientific Reports, doesn’t just add another piece to the puzzle; it dramatically reshapes our understanding of early Mars. The research team, from Hong Kong Polytechnic University, meticulously analyzed high-resolution images from orbiting spacecraft and in-situ measurements from Zhurong. Their findings point to a complex interplay of geological processes shaped by a significant body of water.

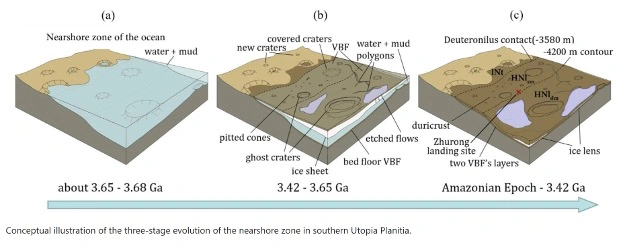

The key to this discovery lies in the identification of distinct geological features: pitted cones, polygonal troughs, and etched flows. These aren’t random formations. Their specific distribution and arrangement, mapped across a vast area, are consistent with the characteristic zones of a nearshore environment—the transition area between land and a large body of water. A beach’s foreshore—the area closest to the water—is distinctly different from the shallows and deeper ocean. The Martian landscape near the Zhurong landing site mirrors this pattern.

The scientists divided the study area into three distinct units based on elevation and feature distribution: a foreshore transition zone, a shallow marine unit, and a deep marine unit. The presence of layered sedimentary rocks and deposits further strengthens the interpretation of a past aquatic environment. Crucially, by analyzing the density of impact craters—a reliable method for dating planetary surfaces—the team established a timeline for the formation of this ancient shoreline. The flooding of Utopia Planitia, they found, likely occurred around 3.65–3.68 billion years ago, during the Late Noachian period, with the shallow and deep marine units forming later in the Early Hesperian.

What do these features actually look like? The pitted cones, small cone-shaped structures, may have formed from mud volcanoes in the shallower areas. The polygonal troughs, characterized by cracked patterns, could be the result of the shifting of an ice sheet or the release of fluids from underground. The layering of rocks and sediments speaks volumes about the deposition of material by water over vast stretches of time.

This research provides strong evidence for a significant, long-lasting body of water in Utopia Planitia during Mars’ early history. It’s a major step forward in understanding Mars’ past climate and the potential for past life, opening exciting new avenues for future exploration and research. The continued work of the Zhurong rover in this region promises even more insights into this captivating chapter of Martian history.

Editor: Zhongxiaowen