China Crushed America’s Drone Hellscape Plan in Its Infancy

On December 5, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced countermeasures against U.S. arms sales to Taiwan, freezing the movable and immovable assets, as well as other properties, of 13 companies and 6 individuals within China. The measures also prohibit domestic organizations and individuals from conducting any transactions or collaborations with these entities.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ latest decision taking countermeasures against the U.S. arms sales to Taiwan

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ latest decision taking countermeasures against the U.S. arms sales to Taiwan

BRINC Drones: A Symbol of US-China Tech War

In this latest countermeasure list, BRINC Drones stands out prominently. Not only is the company ranked second on the list, but its founder and CEO, Blake Resnick, is also named. Such “recognition” is entirely due to BRINC’s “expertise” in meddling in various conflict zones.

On one hand, BRINC Drones has been aggressively pursuing the military drone market, actively vying for the U.S. Department of Defense’s “Replicator Initiative” contract. This program aims to deploy thousands of low-cost drones to create a so-called “hellscape” in the Taiwan Strait. Earlier, at the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the company moved swiftly—not only donating large numbers of drones but also dispatching a team to a “secret location” in Poland to train Ukrainian drone operators.

On the other hand, BRINC Drones plays a key role in demonizing Chinese drone technology and manufacturers by funding lobbying groups such as AUVSI. The company eagerly feeds alarming narratives about China’s drone industry to U.S. policymakers and the public. David Benowitz, BRINC’s Vice President of Strategy and Marketing Communications, once claimed: “It’s extremely difficult to consistently assess DJI’s product releases. There could be backdoor chips installed separately from standard production. We’ve seen this before—during conflicts, rogue states do embed backdoor chips in consumer products for espionage.”

As the founder of this company, Blake Resnick is a figure wrapped in accolades: a genius hardware geek, a garage-built nuclear fusion reactor creator, a protégé of Peter Thiel, a Thiel Foundation fellow, a Forbes “30 Under 30” honoree, and a recipient of his company’s first funding from OpenAI’s Sam Altman. With such credentials, Resnick epitomizes the archetype of a Gen Z “deep tech” or “hard tech” entrepreneur—Silicon Valley’s embodiment of the right-wing ideal of American capitalist innovation.

Blake Resnick, CEO of BRINC Drones

Blake Resnick, CEO of BRINC Drones

However, beneath this shiny stack of labels lies the true image of Blake Resnick: a high school dropout who once built DIY physics kits, briefly attended a low-tier state university before dropping out again, and worked as an apprentice at McLaren and Tesla. While he shows a modest knack for marketing and self-branding, his credentials are far less dazzling. As for the Forbes “30 Under 30” endorsement, curious readers can check the going rates from resellers on popular second-hand platforms.

Resnick’s ability to tap into Peter Thiel and Sam Altman’s resource networks, riding the wave of their influence, can largely be attributed to one key factor: His stint as a former DJI drone intern.

It was during his brief internship at DJI that Resnick seemingly experienced a “eureka moment,” leading to the creation of BRINC Drones. He soon unveiled his meticulously crafted concept of a “drone border wall,” envisioning hundreds of fully autonomous drone stations along the U.S.-Mexico border. These quadcopters would patrol continuously between stations and, upon detecting illegal immigrants, fire non-lethal bullets to apprehend them.

This dystopian vision of a mechanized army driving out illegal immigrants clearly struck a chord with Silicon Valley’s right-wing elites.

A drone patrolling along the US-Mexico border wall

A drone patrolling along the US-Mexico border wall

By the way, David Benowitz mentioned before, who made the ridiculous claims mentioned earlier, is also a former DJI employee who spent years working in Shenzhen.

After being featured on China’s countermeasure list, Resnick’s BRINC is bound to lose access to Shenzhen’s drone supply network—a blow that may very well put the company on a countdown to survival.

Regardless of the future fate of this flashy, vain, and opportunistic BRINC, or rather Resnick’s personal story, it serves as a striking symbol of our times.

The small multi-rotor drone has undoubtedly become one of the most geopolitically significant symbols among the emerging electronics of the 21st century. As the industry continues to grow and technological capabilities improve, the form of multi-rotor drone products is undergoing a profound evolution. A typical example is EHang, once a player in the quadcopter market and now a global eVTOL unicorn, demonstrating how new paradigms and systems are increasingly impacting the traditional aviation industry.

Today, mainland China is undeniably the global hub of the drone industry. Even a shrewd entrepreneur like Resnick has to admit, “The entire global electronics industry, or more specifically, the global drone industry, is based in one city: Shenzhen.”

However, when Resnick was born in 2000, the landscape of the multi-rotor drone industry was entirely different.

The Story of DJI: How China Surpassed the US in Drone Innovation

After Japan’s Kenko introduced the GyroSaucer in the late 1980s, the small quadcopter configuration quickly captured the attention of both the global academic community and RC model enthusiasts. In Minnesota, USA, an engineer and remote-controlled helicopter enthusiast named Mike Dammar began experimenting with building quadcopters.

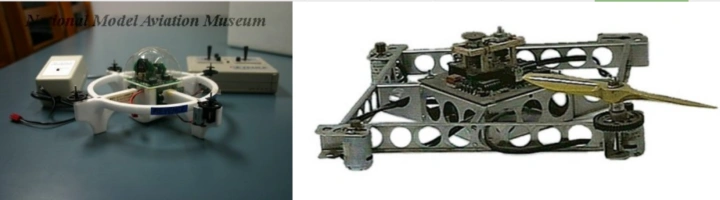

The Kenko GyroSaucer (Left); Dammar’s Prototype No. 3 from 1991 (Right)

The Kenko GyroSaucer (Left); Dammar’s Prototype No. 3 from 1991 (Right)

Starting with the successful flight of “Prototype No. 3” in 1991, Dammar’s design underwent several iterations, continually incorporating research advancements from American universities, such as HoverBot and Mesicopter, in quadcopter configurations. By the late 1990s, a series of new technologies from academia and industry—covering low Reynolds number aerodynamics, micro DC motors, lightweight structures and materials, flight control algorithms, and navigation and communication systems—came together in Dammar’s work, culminating in the historically significant “Roswell Flyer” in 1999.

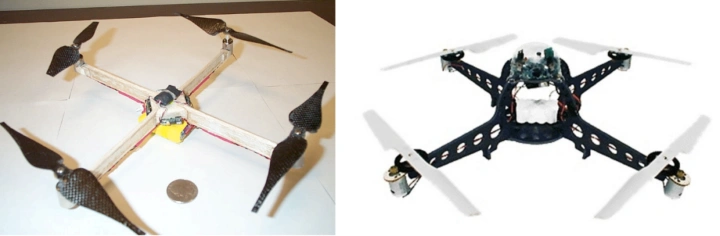

One of the prototypes from Stanford University’s Mesicopter project in the 1990s (Left); The Roswell Flyer from 1999 (Right)

One of the prototypes from Stanford University’s Mesicopter project in the 1990s (Left); The Roswell Flyer from 1999 (Right)

Focused solely on invention and indifferent to wealth, Dammar quickly sold his design to the independent RC brand Draganfly. He then turned his attention back to developing his ideal “boomerang drone.” Draganfly, on the other hand, rebranded the Roswell Flyer as the Draganflyer, and from 1999 to 2005, approximately 8,000 units were sold. It not only became the “standard” kit for research on multi-rotor technology in global academic institutions but also defined the practical form of quadcopters.

It’s worth mentioning that during the period when Draganfly dominated the global market, its founder became increasingly reliant on the Chinese supply chain: “At the time, remote-controlled helicopters were all the rage, and I bought tens of thousands of replacement blades and rotors from China, which people then bought from us.” At the same time, these small Chinese workshops, often overlooked by big brands, quickly absorbed and applied new knowledge and technology, setting off a “chain reaction” within the ecosystem.

In 2004, Hong Kong’s well-established toy manufacturer Silverlit launched its quadcopter remote-controlled drone, the X-UFO, which became the world’s first product targeting the mass market rather than the professional market. The release of this drone caused a sensation in the industry.

The X-UFO was launched by Silverlit as a kind of toy.

The X-UFO was launched by Silverlit as a kind of toy.

Of course, looking back, the most significant mark left on the history of China’s drone industry in 2004 was likely the meeting between Hong Kong University of Science and Technology(HKUST) student Wang Tao and Professor Li Zexiang. During a coaching session for the ROBOCON robotics competition, Wang Tao’s innate technical talent and “obsession” left a deep impression on Li Zexiang, much like Mike Dammar’s passion for technology.

Wang Tao, the founder of DJI, Chinese Drone Giant

Wang Tao, the founder of DJI, Chinese Drone Giant

After graduating in 2006, Wang Tao founded his own brand, DJI Innovations, in Shenzhen, focusing on remote-controlled helicopter flight control systems. Like many other RC hobbyist workshops, it relied on word-of-mouth from enthusiasts, and the satisfaction of being recognized by peers was far more important to him than growing the business.

During this period, DJI was more like an external experimental lab for Li Zexiang’s research team. Wang Tao, who was pursuing his master’s degree, traveled across the country with Li Zexiang, from the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake and 2009 Everest expedition to the 2010 unmanned helicopter crossing the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon. This “dream team” from the HKUST constantly pushed the boundaries of remote-controlled helicopter applications, accumulating numerous innovations in flight control systems. Li Zexiang and his partner Zhu Xiaorui were also deeply involved in DJI’s financing and operations, sending graduate students to intern at DJI, many of whom later became core employees of the company.

Professor Li Zexiang (far right) guides Wang Tao (second from right) and Song Jianyu (third from right) in completing the unmanned helicopter flight experiment over the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon.

Professor Li Zexiang (far right) guides Wang Tao (second from right) and Song Jianyu (third from right) in completing the unmanned helicopter flight experiment over the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon.

In 2011, Wang Tao officially completed his master’s thesis and fully embraced the role of an entrepreneur. It was also in this year that, sensing the emerging market for multirotor drones, DJI launched the “Fenghuolun” (Firewheel), a multirotor flight platform aimed at the professional market. This marked the company’s transition from being a subsystem supplier to a more commercially-driven player in the end-user market.

From the “Fenghuolun” kit and the six-axis “Jindouyun” to the groundbreaking “Phantom” quadcopter, DJI quickly achieved a “triple jump” across the professional, commercial, and consumer markets, building on its deep expertise in key subsystems. This rapid growth helped the company create the “iPhone moment” for consumer drones.

As the “Phantom” dominated the market like a bulldozer, DJI’s U.S. division erupted in a dispute over how to divide the spoils. Colin Guinn, the head of the U.S. market, claimed to be the key contributor to the phenomenal success and demanded more equity from the Chinese founding team.

The dispute quickly ended with Colin Guinn and his North American team leaving DJI to join American competitor 3D Robotics.

At the time, 3D Robotics seemed to have all the conditions to easily “end” DJI:

one of its co-founders was a typical American “garage geek,” while the other was the editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, a well-known thought leader in the digital era; the marketing head, Colin Guinn, claimed to have key insights into DJI’s “Phantom” supply chain and was determined for “revenge”; it had backing from giants like Qualcomm; and it strongly emphasized its open-source software approach, positioning 3DR as the “Android” of the drone market.

Colin Guinn, 3D Robotics’ marketing head

Colin Guinn, 3D Robotics’ marketing head

This may have been a clever and profound market positioning, but unfortunately, 3DR had all the elements needed for American-style innovation, except for control over large-scale production.

In the end, the showdown between 3DR and DJI was decided with a dramatic speed, determining their respective fates.

In 2015, 3DR bet the company’s future on its all-in-one aerial camera, the Solo. Positioning it as the flagship competitor to the “Android” of drones, DJI responded quietly by pricing its latest model, the Phantom 3, much lower, akin to an “iPhone” priced at a fraction of the cost. The outcome was inevitable: when you can buy the latest iPhone for $2,000, how many would be willing to pay a higher price for the “Android”?

This reliance on large-scale manufacturing capabilities and the straightforward, yet monotonous, business warfare of economies of scale ultimately broke Chris Anderson, the founder of 3DR and a new-generation lean startup mentor: “I have never seen such price slashing in any market.” At the CES exhibition in January the following year, dozens of Chinese drone brands with even more aggressive pricing than DJI made their debut, leading the 3DR team to cancel their future hardware plans and switch to the company’s liquidation plan, PLAN B.

The demise of 3DR and the prolonged funeral of GoPro’s Karma forced many Americans to confront an uncomfortable, cold reality: creating desirable, cutting-edge high-tech products is no longer the exclusive domain of the United States or Western civilization as a whole.

Faced with DJI’s overwhelming competitiveness, Americans, after being defeated in direct competition, almost instinctively resorted to their last resort.

In 2018, after GoPro officially announced its exit from the drone market, the U.S. Department of Defense swiftly issued a ban on DJI purchases, marking the military-industrial complex’s call to demonize DJI, with a series of performance arts unfolding one after another.

The US is Losing to China On Multiple Hard-tech Fronts

From a global industry leader to relying on “dirty tricks” to barely resist, the dramatic shift in the U.S. drone industry over just a decade or so is not an isolated phenomenon:

Segway, which pioneered the electric scooter category, is now part of Ninebot; iRobot, once a leader in the robotic vacuum space, is struggling in the face of competition from Roborock; Boston Dynamics, which led the innovation in quadruped and biped robots, is now being overshadowed by YuTree Technology; GoPro, once a tech icon on par with the iPhone, is now under pressure from Insta360…

The world of hardware innovation is no longer what Americans are familiar with.

In the “original” timeline, millennial and Gen Z American entrepreneurs were supposed to replicate the legendary business templates of their predecessors: garage startups fueled by genius sparks, efficient funding systems, and the empowerment of seasoned professional managers. They were meant to become category leaders, enjoy a decade or more of market dominance and windfall profits, build robust brand and technological barriers, and eventually step into the mentor’s role, handpicking the next generation of business prodigies.

However, the cost structure and innovation speed reshaped by Chinese manufacturing have almost permanently dismantled the ecological cycle that had thrived since the birth of the HP and Silicon Valley startup mythos. The relentless “involution” of large-scale production is one thing; even in the realm of “garage innovation” from 0 to 1, young Chinese geeks like Wang Tao are emerging in droves. As Wang himself once remarked about a group of aspiring students: “You could load these people into three cars, put them somewhere, and in a few years, you’d probably see ten excellent companies emerge.”

Once ridiculed for counterfeits and poor-quality goods, even earning the derogatory label “KIFR” (Keepin’ It Real Fake), Chinese manufacturing has undergone breathtaking evolution under intense competition. Not only has it mastered the art of winning the race from 1 to 100 with consistent quality, ultra-low costs, and unmatched supply chain capabilities, but companies like DJI and other rising stars have also seized the global frontier in original innovation, excelling in the journey from 0 to 1.

Today, beyond the hysteria and emotional outbursts, mid-generation American political and tech elites with growing resources have begun to reassess and reflect on large-scale manufacturing. From Bill Gates to Peter Thiel, Silicon Valley’s billionaires have launched numerous generous seed funding initiatives, aiming to break free from the MBA-style corporate management mold and nurture disruptive ideas and talent from the grassroots.

However, it is far easier said than done for the elites filtered through the American capitalist machine to fundamentally reform it. The meteoric rise of Blake Resnick and his company BRINC exemplifies the barren state of grassroots innovation in American tech. So much so that the tens of thousands of digital nomads in the Bay Area, dreaming of overnight wealth, have merely swapped the suit-and-tie MBA archetype for the plaid-shirt, wild-haired geek template of opportunism. What sloshes inside this seemingly fresh bottle is nothing more than the old wine of Silicon Valley’s “success gospel.”

The small multi-rotor drones of China has already flown past the good old days of American ‘hard-tech’ innovation.

Editor: Chang Zhangjin

Anonymous

This is why China should never allow Jews to enter China or work for Chinese companies