Trump’s True Demands from China

Q7

The China Academy: It’s very interesting. The U.S. and China are on very different trajectories. China is taking a firm stance, saying, “We need to open up.” On the other hand, the U.S. is focusing on contraction.

Louis-Vincent Gave:Yes, and Trump has been very focused on building “Fortress America,” etc. Having said all this, I think if you’re China, your big fear when Trump was elected was very different.

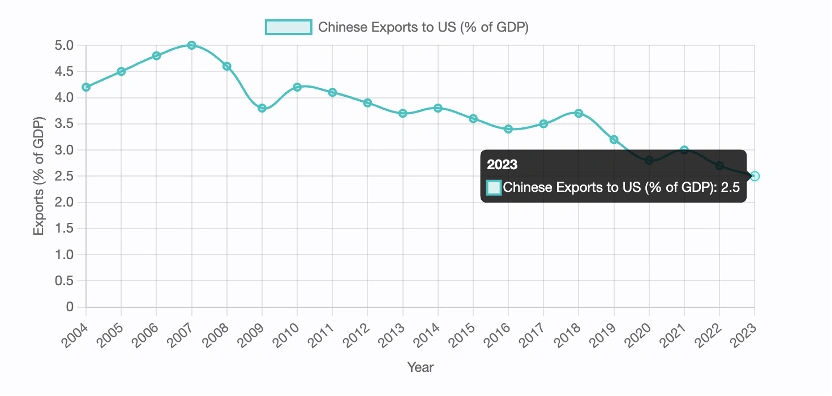

Three months ago, the big fear wasn’t that Trump would slap a bunch of tariffs on Chinese goods. To be perfectly blunt, China doesn’t really care about that anymore. If you go back a decade, Chinese exports to the U.S. made up 8% of China’s GDP. Now, it’s only 2.7% of GDP. So, it doesn’t matter as much as it used to.

I think the real fear for China was that Trump might try to build an anti-China coalition. That he would go to Europe, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Australia, Canada, Mexico, and say, “Hey, you can’t do business with China anymore. You can’t let them build factories here. You can’t trade goods with them. You’ve got to block out China. I’m blocking China, and you have to do it too.”

Well. But fast forward to today, and now if Trump goes to Europe and says, “Hey, if you don’t block out China, we’re not going to be friends,” Europe might reply, “We’re already not friends. What are you talking about? You can’t tell us what to do.”

So, in that respect, you might say Trump’s policies are bad news for China and could crush confidence, etc. But if I’m Xi Jinping or Li Qiang, I might think Trump is actually good for China. Why? Because he wants to close America off from the world. Perfect! That allows China to do more business with Indonesia, Thailand, and other countries.

Today, if you’re Thailand or Indonesia and you see how Trump treats countries like Ukraine, Canada, and France—countries that are nominally friends of the U.S.—you might start thinking, “The U.S. is not a very stable friend. Should I turn my back on China and do more with the U.S., or should I strengthen ties with China?”

I need to do more with China and less with the U.S., right? That’s probably what they’re thinking. And that’s what matters more to China right now. Can China grow its business with Indonesia? Can it grow its business with Saudi Arabia? With Brazil? These are the big questions. And today, I think that’s much more likely than it was a few months ago.

It’s China’s chance right now. I think it is, especially when it comes to Southeast Asia. Where the U.S. closing in on itself opens up huge opportunities for China. What China should do now is pursue friendly diplomacy.

China could say, “Look, we just want to be friends. Let’s do more business together. We’re not here to bully you. Sure, we could bully you because we all know the U.S. isn’t going to protect you, but that’s not who we are. We’re here to do business. Let’s be friends and achieve mutual benefits.” This is a huge opportunity for China.

Q8

The China Academy: The expectations of a U.S. economic recession are growing. The stock market has experienced some turbulence over the last week and last month, and U.S. Treasury bonds are also on shaky ground. Can Trump alleviate the crisis in the U.S.? And what impact will the instability of the U.S. economy have on the global economy?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I think this time around, Trump is very different from the first time he was president. Back then, Trump was always tweeting about the stock market and constantly talking about it. This time, however, Trump has a much bigger challenge on his hands.

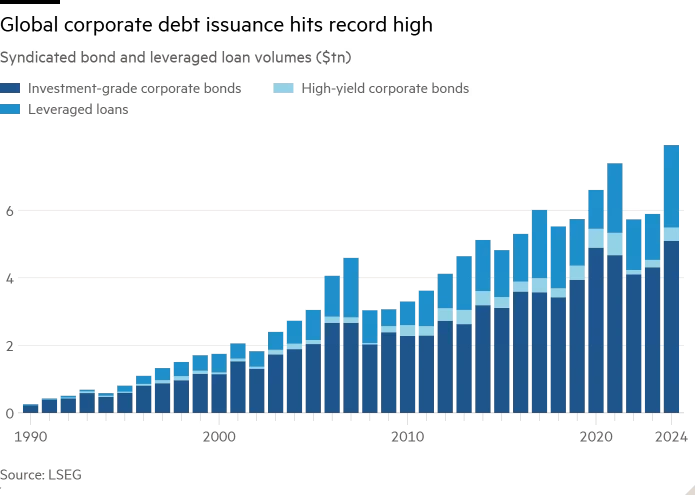

Few people realize this—or even remember—but five years ago, when COVID hit (pretty much exactly five years ago), U.S. corporations went out and borrowed a lot of money. Interest rates were at zero, so they issued record amounts of debt—tons and tons of corporate debt. Now, most corporate debt in the U.S. is structured with a five-year term. That means these corporations have to roll over their debt in the second half of this year and the first half of next year.

This is a big problem for Trump, because as these corporations roll over their debt at much higher interest rates, they’re going to stop capital spending. They’ll start firing people, reducing expenses, and this could very well push the U.S. into a recession at precisely the wrong time—right before the midterm elections.

And the last thing Trump wants is for Democrats to win during the midterms. If they win, they’ll push for impeachment and other political battles, leaving Trump with two years just fighting the Democrats.

So if you’re Trump, your main goal today is to get interest rates down. Otherwise, corporations won’t be able to roll over their debts. He’s doing everything he can to achieve that—reducing government spending, pressuring foreign governments to buy long-dated U.S. bonds, and talking down economic growth.

The current U.S. policy is therefore aimed at lowering bond yields. And if you get lower bond yields, you also get a weaker U.S. dollar.

Now, the third part of Trump’s policy is to get lower energy prices. That’s why he was so willing to throw Ukraine under the bus. Essentially, he wants Russia to start producing more oil. Before the Ukraine war, Russia was producing roughly 10.5 million barrels of oil per day. Now, it’s producing only 9 million barrels per day.

For Russia to ramp up production, they’ll need companies like Halliburton, Schlumberger, and other Western oil service firms to upgrade their equipment. Trump’s policy is therefore very simple: lower interest rates, lower the dollar, and lower oil prices.

It doesn’t mean he’ll succeed, but those are his three main goals.

If he’s successful in these goals, it’s great news for many markets. For example, if you’re China, how great would it be to have lower interest rates, a weaker dollar, and lower oil prices? It would create a boom.

If you’re the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), you’d be able to keep your interest rates low, and everything would run smoothly.

In summary, I think the odds are pretty high that these are the policies the U.S. will pursue: lower interest rates, a weaker dollar, and lower oil prices. If that’s the case, there’ll suddenly be more exciting opportunities in global markets than just buying U.S. equities.

Q9

The China Academy: But if Trump wants to decrease the interest rate, will he give up the tariffs? Because tariffs could worsen inflation.

Louis-Vincent Gave:You’re right—the tariffs do seem contradictory to that goal.

So here’s the big question: are the tariffs a goal in themselves, or are they just a tool to achieve something else? I still think that, for Trump, tariffs are a tool to achieve something else.

What he wants is to sit down with Xi Jinping in June and say, “Look, either I’m going to impose a bunch of tariffs, or you’ve got to buy a lot of my bonds. I’m going to issue some 50-year zero-coupon bonds, and you’re going to buy those.”

And he’s going to say the same thing to the Europeans, the Japanese, and the Koreans: “You guys have big trade surpluses with the U.S. So either I’ll impose tariffs to reduce the trade surplus, or you take that surplus and invest it in my 50-year zero-coupon bonds.”

I think tariffs are really just a tool to get foreign governments to fund the U.S. deficit. When you listen to Trump’s rhetoric, it always comes back to the same theme: “The foreigners will pay.”

For example:

“The Mexicans will pay for the wall.”

“The budget deficit? We’ll sell U.S. citizenship for $5 million each.”

“The tariffs will pay for themselves.”

It’s always about foreigners footing the bill.

So I still believe that tariffs are a tool—not the end goal in themselves.

Q10

The China Academy: The Chinese market hasn’t reacted significantly to Trump’s tariffs, why is that?

Louis-Vincent Gave:You’re right. Judging from the market’s reaction, it doesn’t seem to matter much for China.

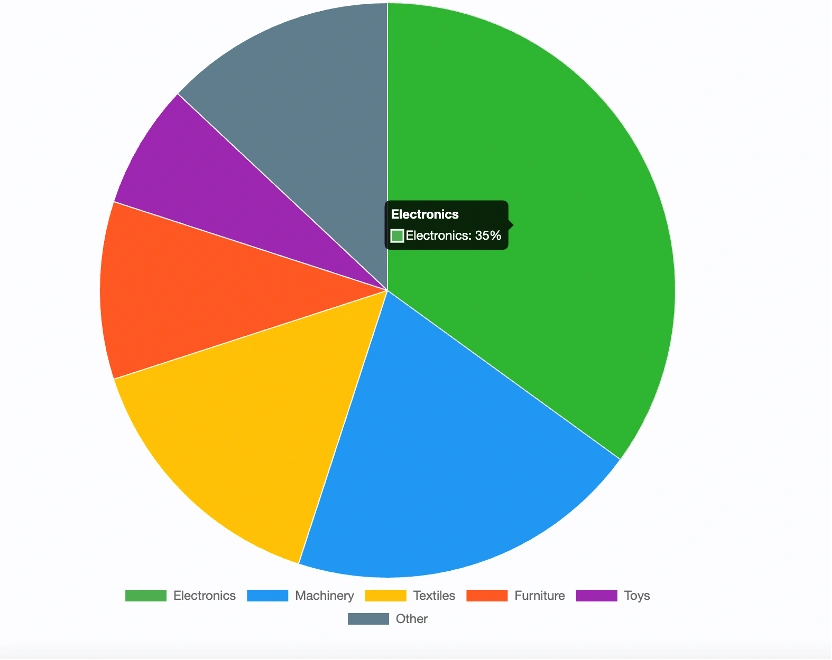

To be perfectly honest, if you look at what China exports to the United States, roughly speaking—and I’m rounding the numbers—it breaks down like this:

About 20% of exports are tied to Apple. If the U.S. wants to put a bunch of tariffs on Apple products, so be it. Who cares?

Another 20% is high-end electronics. These supply chains are incredibly complex and can’t easily move to places like Vietnam or India.

Then there’s another 20% that’s machine tools—both high-end and low-end. This includes things like Black & Decker products or Johnson Motors. Conceptually, this part could move elsewhere, but it’s not happening quickly.

Finally, the remaining 40% is the low-value-added stuff: shoes, T-shirts, Tupperware, furniture, plastic toys, etc. This part is already gradually leaving China, moving to countries like Vietnam and Indonesia.

The Chinese leadership doesn’t seem to care much about losing that last 40%. They know it’s leaving anyway. Low-value-added industries like shoes and toys are bound to relocate over time.

So, when you put this all together, exports to the U.S. account for only 2.7% of China’s GDP. That’s why the Chinese market doesn’t really care about the tariffs.

In fact, the market has already priced in the deterioration of U.S.-China relations, which started back in 2018. The fact that relations are bad is no longer news—it’s already baked into the market.

What’s not priced in, however, is the possibility of relations improving.

Now, if Xi Jinping and Trump meet in June for their rumored “joint birthday summit”—because Xi’s birthday is June 15 and Trump’s is June 14—and if they get along and sign some kind of deal, that would be a huge catalyst for the markets.

If that happens, it’ll be a big celebration—not just for their birthdays, but for the markets too.

Q11

The China Academy: This is definitely something to look forward to. From an investment perspective, what are the key geopolitical risks to watch this year? Particularly in light of Trump’s strategy of retrenchment, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future trajectory of U.S.-China relations?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I tend to have an optimistic outlook most of the time.

That said, I also believe people worry too much about geopolitics affecting markets. Yes, bad geopolitical headlines can have an impact, and to be fair, the deterioration of U.S.-China relations over the past 5–6 years has had a significant effect. So I don’t want to completely dismiss those concerns. There is an element of risk there.

Now, looking ahead, Xi Jinping and Trump are most likely going to meet in June. Here’s what I think will happen between now and then: In April and May, Trump will ramp up his rhetoric against China. On April 1st, the Commerce Department, Treasury Department, and USTR are set to release their recommendations for tariffs.

During this time, Trump will repeatedly threaten China with a slew of tariffs and will publicly “beat up on China.” This is classic “Art of the Deal” strategy: you beat up your opponent first, and then sit down to negotiate. Once the other side feels pressured, you extract concessions from them.

If you’re Xi Jinping, you’re not going to respond during April and May. You’ll let Trump do all the talking while you keep a low profile. Then, in June, you sit down with Trump, strike a deal, and everyone walks away feeling satisfied. This sets the stage for a strong second half of the year.

To me, that seems like the most likely scenario.

Q12

The China Academy: What Is the Biggest Geopolitical Risk for Investors This Year?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I think the biggest risk to this plan would be a sudden spike in oil prices.

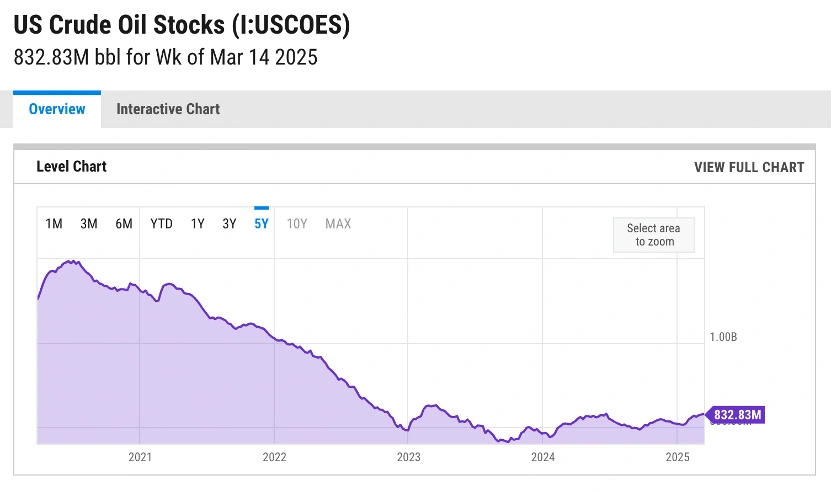

We’ve grown accustomed to a world of relatively cheap oil in recent years. However, global oil inventories have been significantly drawn down:

U.S. oil inventories are near 20-year lows. China, which usually holds high oil inventories, is currently running low. The same is true for Japan.

Now, I’m not saying oil prices are going to surge, but let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario. For example, suppose Trump decides to bomb the Houthis in Yemen. In retaliation, the Houthis could turn around and target Saudi Arabia’s refining facilities as payback, reasoning, “We can’t attack the U.S. directly, but we can hit Saudi Arabia, their ally.”

Again, I’m not saying this will happen, but if it did, oil prices could quickly jump to $100, $110, or even $120 per barrel.

In such a scenario, the Federal Reserve would likely raise interest rates to combat inflation, and markets would sell off sharply.

While I don’t think this is a likely outcome, you asked about risks, and for me, this is the one I worry about most. A sudden surge in oil prices could throw everything off balance.

Editor: huyueyue

Anonymous

One can’t eat his cake and have it. As you make your bed so you lye on it. It’s like you buy a thing, use it up and go back to the seller to ask for your money back.