Through 10 years of Developing Africa, China Learns Much

The Changing Landscape of Global South’s Development

There has been a crisis, in my view, dating back to the 1990s as part of the Washington Consensus, where multinational corporations effectively took over the management of the world. These corporations became the midwives of the neo-liberal system. One of the tactics they mastered was corrupting Africa’s skilled bureaucrats. They promoted the idea that it was better to outsource functions and establish independent agencies rather than invest in building strong, capable bureaucracies.

In many of the countries plagued by rampant corruption, such issues become possible when the bureaucracy is weakened. With fragile institutions, borders become porous, and the system is overrun by individuals lacking proper training, orientation, and skills. This happens because the private sector essentially took over the management of these states.

One of the leading economists, Mariana Mazzucato, who is based at University College London, has written a book titled The Big Con.

In the book, she discusses the role of major consulting firms. She argues that these firms have essentially “conned” everyone into believing they possess superior capacity to manage state affairs. However, now in countries like South Africa, firms such as KPMG have faced serious scandals. In fact, KPMG’s presence in South Africa today is only a fraction of what it was 20 years ago.

KPMG International Limited is a multinational professional services network, and one of the Big Four accounting organizations

KPMG International Limited is a multinational professional services network, and one of the Big Four accounting organizations

Several major consulting firms have been banned or significantly diminished. Some of the multinational firms have also seen their operations shrink here in China.

In many cases, these consulting firms became substitutes for the state and a robust bureaucracy. This undermined ethical boundaries, made systems more vulnerable, and opened the door to corruption and looting from within.

Moving forward, what we need is a new kind of pact that addresses the evolving landscape. For instance, Africa is now dealing with a different set of multinational corporations—Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)—which have become global players.

To navigate this shift, it’s crucial to implement safeguards and ensure that these new multinationals operate in a way that supports sustainable development rather than undermining local institutions.

African leaders and bureaucracies must have the capacity to negotiate the best possible deals for their citizens—deals that are transparent and fair. Achieving this not only ensures better outcomes for the people but also fosters trust, legitimacy, and popular support.

Such an approach can also serve as a shield against the Western narrative, which often criticizes Chinese multinationals more harshly than their American counterparts. By maintaining fairness and transparency, African nations can push back against these double standards and focus on partnerships that genuinely benefit their people.

You’ll often find Chinese state-backed construction companies bidding for projects in Africa, competing with European and North American firms. When a country has strong state capabilities, it can negotiate the best contracts—ones that are transparent, fair, and equitable. In many cases, the Chinese companies will emerge as winners because they offer superior technology, greater capacity, and better financing terms. This fosters legitimacy on the ground, which is critical.

The real issue arises when agreements are opaque or lack accountability. One of the biggest challenges—or dilemmas—facing Chinese companies and the Chinese government is constitutional requirements in countries like South Africa.

South Africa’s constitution mandates that public funds cannot be spent through exclusive, government-to-government agreements. Instead, the procurement process must be transparent, fair, and equitable, requiring some form of competitive bidding. This creates a unique dynamic that must be managed carefully to ensure compliance and trust. Many Chinese firms are adapting to these legal frameworks and have begun competing effectively in this space by participating in competitive bidding processes and adhering to local regulations.

In some countries, two presidents can meet, sign an agreement, and the project begins the very next day due to their different constitutional frameworks. However, in South Africa, that’s not possible. You can’t have two presidents simply sign off on building a railway and start construction the following day. The process must be fair, competitive, and equitable.

For state-backed projects, you need to issue a tender, clearly stating: “We are looking for a partner to build this project, and this partner must be state-backed.” In such cases, Chinese firms are likely to win because many other countries don’t have strong state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to compete.

This is especially true for sectors like nuclear energy. No country has ever procured nuclear technology from a private firm without government backing—because these projects require state involvement and guarantees. The same applies to arms procurement, where countries exclusively deal with state-backed firms. These industries operate on a foundation of trust, sovereignty, and government-to-government agreements. And people are beginning to appreciate this.

On September 4, 2024, CGN Energy International signed a comprehensive agreement on financing and power purchase and supply for the South Africa TFC Photovoltaic Direct Power Supply Project with the China-Africa Development Fund, Conna Holdings Limited, Samancor Chrome, and the Johannesburg Branch of China Construction Bank.

On September 4, 2024, CGN Energy International signed a comprehensive agreement on financing and power purchase and supply for the South Africa TFC Photovoltaic Direct Power Supply Project with the China-Africa Development Fund, Conna Holdings Limited, Samancor Chrome, and the Johannesburg Branch of China Construction Bank.

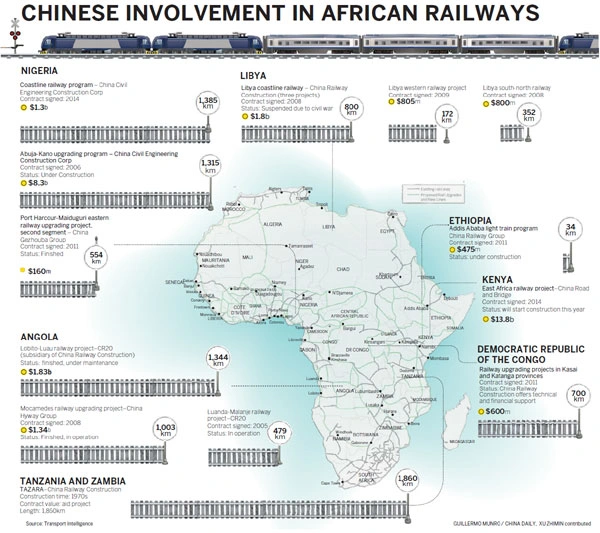

30 years ago, if countries in the Global South wanted to build a railway line, there were very few options available. The pricing structure of such projects was different, and funding sources were limited. Today, however, there are far more options, largely due to China’s involvement.

Just think about it: in countries like the U.S., General Electric today would struggle to even bid on one mega rail project. It would be very difficult. But 30 years ago, for a similar project, constructing a railway line without General Electric being part of the equation was almost unthinkable.

So, there have been significant shifts. If you’re building high-speed rail today, North American companies might handle project management, but not provide the key technologies. The competition now is primarily between the Chinese, the Japanese, and the French. This reflects the dynamism that has been introduced into the market for these mega projects.

And then there’s the issue of financing. Thirty years ago, funding for public infrastructure projects was quite limited. Today, you have options like sovereign wealth funds that didn’t exist back then. There are also more build-operate-transfer (BOT) models available, where Chinese state-owned enterprises or European companies, for instance, can build, operate, and later transfer the project. Thirty or forty years ago, such options were much more constrained.

Now, this opening up of space for development options, when managed by skilled and competent bureaucracies with mission-driven leadership, enables the Global South to accelerate its development patterns. The environment today is significantly more open and conducive compared to 30 years ago. Back then, your options would have been largely restricted to particular multinational corporations.

Today, markets are more diverse and intensely competitive. The key challenge, however, lies in how the terms and conditions of contracts are drafted. If the terms are not well-defined and robust, even the most affordable and seemingly reasonable concession can appear exploitative to the public due to weak contracts and a lack of transparency.

The Evolution of the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa

In communities where bridges, roads, and railways have been built, people view these as corridors of trade and channels for fostering people-to-people connections, which they readily embrace and utilize. Here is where challenges emerge. In many cases, particularly in the first generation of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, the biggest mistake on all sides was poor communication. People believed there was a lack of transparency, they didn’t understand the terms and conditions of the agreements, and they didn’t feel involved in the process. As a result, projects were often perceived as “white elephants” or corrupt arrangements. By and large, this stems from inadequate communication, which in turn makes these initiatives an easy target for criticism.

White elephant is a metaphor used to describe an object, construction project, scheme, business venture, facility, etc. considered expensive but without equivalent utility or value relative to its capital (acquisition) and/or operational (maintenance) costs.

White elephant is a metaphor used to describe an object, construction project, scheme, business venture, facility, etc. considered expensive but without equivalent utility or value relative to its capital (acquisition) and/or operational (maintenance) costs.

What do we expect in Africa? Simply because Chinese workers came to build the railroad, the local people should cheer for them in the villages? That approach was absolutely irresponsible for both the Chinese side and African leaders who allowed it to happen. This is why it’s crucial to write clear conditions into contracts: when building a project, we will invest in fixed capital and lead to broader growth. For example, you are opening corridors of trade by enabling better movement of people and goods. Alongside the infrastructure, you could develop housing to support communities, integrate agriculture, and beneficiate minerals. It is vital to include clear terms about building local skills so that there is a meaningful transfer of knowledge and expertise. People need to see and understand the tangible benefits of such projects for their own lives and communities. By doing this, you legitimize the project, making it more sustainable, and then people will defend it.

In addition, the first generation of Belt and Road (BRI) projects were often implemented hastily—especially in the initial five years or so. These projects were not always carried out by the most skilled or experienced Chinese engineers. For instance, projects like the rail system in Angola reflected some of these shortcomings. At that time, people perceive the projects as extractive—when a platoon of Chinese workers arrives, completes a project within 24 hours, and departs—which aroused resentment among the local population. You wouldn’t do that today. But in the first generation, that was really happening. That, in turn, provided an opening for others to critique and undermine China’s efforts.

Now, China’s way of building the Belt and Road Initiative is totally different from 10 years ago. We now see a shift toward greater transparency, improved communication, and more inclusive approaches. Efforts are being made to involve local communities, explaining why infrastructure like roads and railways is being built and how it will benefit them. Furthermore, the Chinese SOEs currently implementing these projects are typically first-tier SOEs. I believe everyone has learned from the past. The terms are becoming more transparent and mutually beneficial, because, to my knowledge, there has never been a project where the Chinese refused to facilitate skills transfer.

Advice:Toward a New Model of Partnerships in the Global South

Finally, I believe one key lesson for Chinese firms in the Global South is the importance of investing in communication. You can’t assume that people will simply embrace a project just because you’re building a road. If you neglect this, you risk triggering resentment, with people perceiving a lack of transparency in your projects. It’s crucial to also invest in building local talent and capabilities. Just like during the rail projects in Indonesia, young people were taught by Chinese engineers to study and learn how to operate the system, this approach makes the project more legitimate and sustainable.

Editor: Chang Zhangjin