There’s No Better Time to Invest in Chinese Assets

Q1

The China Academy: Recently, there seems to be a shift in the Western media’s narrative about the Chinese market. Voices expressing optimism about China are increasing. Do you think a bull market in China is really coming, or is this just a temporary uptick driven by the Chinese government’s stimulus policies and the emergence of technologies like DeepSeek?

Louis-Vincent Gave: I think it’s primarily driven by the shift in Chinese government policy and the release of DeepSeek. I do believe this marks the start of an important bull market in China. We are witnessing a very significant shift in narrative, both among domestic and foreign investors, as they reassess Chinese equities.

For me, the key shift is straightforward, and it really begins here. In my career, I’ve probably seen three or four pivotal shifts in Chinese policy. If you go back to the 1980s and 1990s, the big story in China was the liberalization of the labor market and the entry of foreign companies through joint ventures. That was the first wave. Then, in the early 2000s, the markets were largely driven by real estate deregulation, which fueled a 20-year real estate bull market.

That came to an end in 2018, when the government decided to restrict loans to the real estate sector. Instead, it shifted focus, directing loans into industrial development. This was driven by the realization that the U.S. was attempting to contain China by restricting access to high-end semiconductors. Tomorrow, it could be industrial robots or something else. To counter this, China prioritized building its own industrial resilience. For six years, nearly all of China’s financial resources were funneled into strengthening its industrial base.

Fast forward to today, and China now essentially dominates industries worldwide, even at the cutting edge of technology. This brings us to DeepSeek. I think DeepSeek is significant because it demonstrates that, even at the highest levels of technological innovation, China can not only compete with the West but, in some cases, surpass it. This gives the Chinese leadership a great deal of confidence. Suddenly, the fear that China’s growth could be stifled by a Western blockade has dissipated.

We are now entering a new phase where the leadership is emphasizing boosting domestic consumption and strengthening the domestic consumer market. One of the simplest ways to do this—and to restore confidence, which is something China currently lacks—is by driving a stock market bull run. I believe this process began in February 2024. Over the past year, Chinese stocks have been steadily climbing.

I think a Chinese equity bull market is underway. Foreign investors are just starting to wake up to it, and domestic investors are beginning to recognize it too. Capital flows are picking up, but this is only the beginning of a story that could unfold over many years.

Q2

The China Academy: Many people remain skeptical about China’s economic fundamentals, especially after the government recently announced a 5% growth target. Challenges like the sluggish real estate sector, local government debt, and weak domestic demand continue to weigh on growth. So, what’s your outlook on China’s economic fundamentals for 2025?

Louis-Vincent Gave: First, I’d say the correlation between economic growth and stock market performance is not very strong. You can have a good stock market with a bad economy, or a good economy with a bad stock market. The two don’t always move in tandem.

Second, I’m sure you’ve heard the saying, “Bull markets climb a wall of worry.” That’s exactly what bull markets do—they push through concerns and uncertainties.

Right now, we’re seeing that behavior play out. It’s very typical. Everyone is focused on the negatives, partly because we’ve had three to four years of a really bad stock market. People are fixated on the bad news: weak real estate, low confidence, and other challenges.

But the market just keeps moving ahead, which is a hallmark of how bull markets evolve. The time to worry about a bull market is when everyone is overly optimistic—when people think it’s all sunshine and rainbows, and everything looks perfect. That’s when you should be cautious. In China, we’re not at that point yet.

Now, to answer your question about China’s economy: There’s no doubt that the Chinese economy has gone through five or six very tough years. Some of this was self-inflicted, to be honest. The extended COVID lockdowns severely hurt people’s confidence.

However, if you take a step back, China’s economy is still, by far, the most competitive in the world. This is evident in China’s trade numbers—its trade surplus continues to hit new highs every month. Right now, China’s trade surplus is around $90 billion per month. That’s $90 billion in U.S. dollars, which no country has ever achieved before. It’s a testament to the competitiveness of Chinese businesses.

China Balance of Trade

China Balance of Trade

Look at any industry—automobiles, industrial robots, train-building, power plants, solar panels, batteries—you name it. China is at the top of the global game, to the point where very few can compete.

Given this, what should be happening? The businesses making money from selling solar panels, batteries, and other exports should be reinvesting domestically or spending that money. But because confidence has been so badly shaken, people are afraid. They’re doing one of three things with their money:

Leaving it in the bank: With no demand for credit, banks have little to do with the money except buy bonds.

Buying gold: Gold is a safe haven. When people buy gold, it’s a sign of fear—it’s a way of saying, “I don’t know what to do with my money, but at least gold will hold its value.”

Keeping money abroad: For example, in Hong Kong, U.S. dollar bank deposits have grown by $250 billion over the past few years—a staggering amount.

Now, if the Chinese government can manage to restore confidence—among both businesses and individuals—the money is there, and it keeps coming in at $90 billion per month. All that’s needed is a boost in confidence.

The easiest way to rebuild confidence is to get the stock market moving up. When people see stock markets rising, they think, “Things can’t be that bad if the markets are doing well.” It’s not just about making money in the stock market; it’s about the psychological impact. Rising markets send a signal that the economy is stabilizing.

This is why stock market gains are so important, and why I think they’ll continue. They’re essential for rebuilding the shattered confidence of both businesses and average consumers.

The best thing that could happen to restore confidence would be for real estate prices to start recovering. A significant loss of confidence stems from the real estate downturn. Many people borrowed heavily to buy property, and when prices plunged, their balance sheets took a huge hit. Fixing this issue would go a long way toward restoring confidence.

The money is there, and China remains highly competitive. If confidence is mended, the economy will eventually find its footing.

So, I actually think the government’s 5% growth target is achievable.

Q3

The China Academy: You’ve mentioned on several occasions that the West generally underestimates or overlooks China’s breakthroughs in high-end manufacturing. Could you elaborate on that?

Louis-Vincent Gave: Absolutely. I think this is one of the biggest issues. My company has an office in Hong Kong, where I’m speaking from today, and we also have an office in Beijing. Unfortunately, we don’t have one in Shanghai, but pre-COVID, we used to have Western investors and CEOs of large companies visiting our offices in Beijing or Hong Kong almost daily—sometimes two or three a day.

Then COVID changed everything. During the pandemic, nobody traveled, and China was essentially closed to the world for three years. Once COVID ended, Russia invaded Ukraine, and many Western investors and CEOs started to view China as “Russia’s friend.” This led to the perception that China is “uninvestable,” so they decided not to bother visiting or investing anymore.

As a result, very few Western business leaders have traveled to China in the past five years, which is crazy when you think about it. China is the second-largest economy in the world—on some measures, you could even argue it’s the largest. And despite the challenges, it’s still growing decently.

More importantly, as we were discussing earlier, China has made remarkable breakthroughs in so many industries. A very obvious example is the automotive industry. Just walking around the streets, you’ll see a plethora of car brands that didn’t even exist five or ten years ago, producing high-quality vehicles at very affordable price points.

The Western world has completely missed out on this story.

I keep telling people: you have to see China for yourself. You can’t underestimate how much it has changed in just five years, across so many fronts. It’s not just manufacturing—it’s fintech as well. Everything in China is now done through mobile phones. If you land in Beijing or Shanghai and don’t have Alipay or WeChat Pay on your phone, you’re in trouble. It will be difficult to order a taxi or do much of anything. The economy has evolved so rapidly in just five years that it’s hard to grasp if you haven’t experienced it firsthand. I try my best to explain this to our Western clients, but I don’t think I do a good enough job—because most people don’t seem to believe me.

About a year ago, I wrote a piece called Prejudice And China. I think the skepticism stems from several factors. Some people are simply holding on to outdated prejudices. They might have visited China 10 or 15 years ago when it was an economy focused on producing cheap goods at low quality. Back then, “Made in China” was synonymous with cheap and inferior products.

If you haven’t visited China in the past five years, you’re probably still clinging to that outdated frame of reference, which no longer applies.

Another significant reason for the skepticism, especially among Westerners, is that China is a communist country. For many in the West, communism is equated with failure. People of my generation—I’m 50 years old—grew up watching the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union. For us, the Soviet Union was an economic disaster. Shops were empty, people had nothing to buy, and the entire system eventually fell apart.

The assumption for many Westerners is: “It’s communist, so it’s going to fail—just like all the other communist countries.”

But here’s what’s fascinating: the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been in power longer than the Soviet Union existed. The Soviet Union lasted from 1917 to 1991. The CCP has already surpassed that timeline. And unlike the Soviet Union in its final years, China doesn’t feel like it’s collapsing. In fact, it’s the opposite.

China is building better trains, reducing pollution, constructing new airports everywhere, and even producing its own airplanes. They’re sending missions to the far side of the moon.

I think the communist label contributes significantly to the bias, but there’s also another factor: the perception that Asians, in general, aren’t creative. In the West, there’s this lingering belief that creativity is a Western monopoly.

We’re often surprised when Asians outperform expectations. Historically, this has been seen time and time again—whether it was the Japanese defeating the Russians in 1905, their successes in World War II, or the Vietnamese defeating the French and later the Americans.

There’s a tendency to underestimate the resilience and hard work of Asians. Even today, I was being interviewed by an American TV channel, and the first question they asked me was, “But isn’t it true that there’s no creativity in China?” I responded, “How do you figure that? China is producing better cars, better movies. Have you seen Ne Zha 2? It’s the highest-grossing animated film in the world. The evidence is there, but people continue to hold on to these outdated prejudices, even when they’ve been proven wrong.”

Q4

The China Academy: While China has shown strong performance in certain industries, some critics argue that competition among Chinese companies is excessive, leading to very low profit margins. Market share may be expanding, but companies aren’t making much money. How do you see this? Is it a problem?

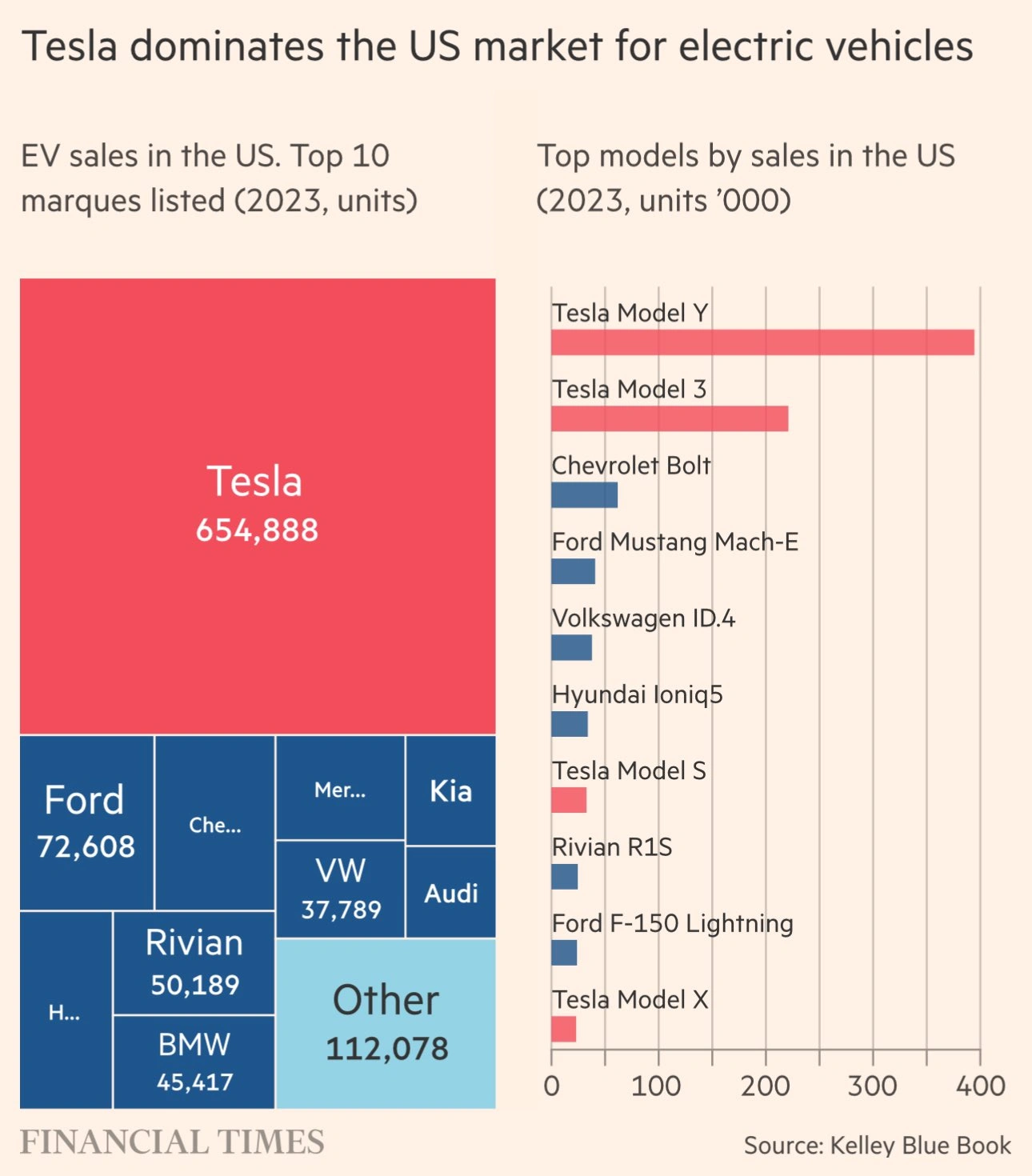

Louis-Vincent Gave: I think it’s true, but that’s what capitalism is about. I’ve said this in many podcasts: if you look at the U.S., for example, when they decide to push for electric cars, the government essentially tells companies like Ford, GM, and Tesla, “We’ll give you big subsidies to develop electric vehicles.”

If GM and Ford fail, and Tesla succeeds, the end result is that you get a Tesla that costs $70,000, and Elon Musk becomes worth $100 billion, or whatever the figure is.

In China, capitalism works differently. In China, when Xi Jinping says, “We need to produce electric cars,” every local party secretary, mayor, and provincial governor takes that as a directive. They say, “The big boss wants electric cars, so I need to make sure we produce them.”

What happens next is they call their local bank—let’s say the Agricultural Bank of China—and say, “I have a local car producer here. You need to give them loans to start producing electric cars.” Before you know it, there are 130 electric car manufacturers in China.

This is what I’ve come to call the “Hunger Games of capitalism.” If you’ve seen the movie The Hunger Games, it’s about a group of kids who are forced to compete and eliminate each other. That’s exactly what happens in industry after industry in China.

But the ultimate winner is the consumer. Instead of having one company like Tesla, with a single person worth $100 billion, China ends up with many car companies. As a result, Chinese consumers today have access to a wide range of electric cars that are not only much cheaper than those available elsewhere but, in many cases, also better in quality.

This is how capitalism is supposed to work—with more competition. Capitalism isn’t supposed to result in one or two companies, like Microsoft, Google, or Tesla, monopolizing an industry, making huge profit margins, and spending large sums lobbying the government to maintain their monopoly positions.

True capitalism is about companies competing and often operating on very slim margins.

Now, for shareholders, it’s obviously better to invest in a monopoly company—that’s much more profitable. But for consumers, the more competition, the better.

You can’t understand China’s economic progress, its growth, or its advancements without appreciating the intense level of competition Chinese companies face. To be a successful businessperson in China, you have to deal with insane levels of competition. If you don’t run twice as fast as your competitors, you won’t survive. It’s a very tough environment to do business in—there’s no doubt about that. The end result is that consumers gain access to high-quality goods at affordable prices.

That’s one part of the equation. The other part is a government that consistently delivers on infrastructure. It builds the roads, railroads, airports, and the electricity grid—essentially all the backbone infrastructure needed to support a modern economy and industry.

Now, some critics argue that China has overinvested in infrastructure, and that’s probably true. But if you’re the Chinese government, the question becomes: “Do we want to overinvest or underinvest?” If you underinvest, you end up with power outages and shortages, which hurt industries and the economy.

So, the entire system in China is built around excess competition and excess investment. That’s just how it works. But that’s also how you achieve rapid progress. It’s how you lift 600 or 700 million people out of poverty.

Q5

The China Academy: The Chinese government has recently sent positive signals about supporting the development of private enterprises. During the Two Sessions, the Premier also expressed support for foreign investment and announced plans to ease restrictions on foreign entry into industries such as telecommunications and finance. How do you view this shift? And how do you think the CPC balances its ideological stance with the need to promote capital development?

Louis-Vincent Gave: Today, if you’re sitting in a leadership position in China, your number one challenge is figuring out how to boost confidence. This isn’t just about achieving economic growth—it’s much bigger than that.

Six or seven years ago, the biggest problem China faced was how to cushion its economy from U.S. attacks. When the U.S. cut off access to semiconductors, it was a very scary moment for the leadership. They realized that if it was semiconductors today, it could be something else tomorrow.

The solution at the time was to build up China’s own industrial supply chains and achieve self-sufficiency in every critical industry. Fast forward to today, and that challenge has largely been addressed.

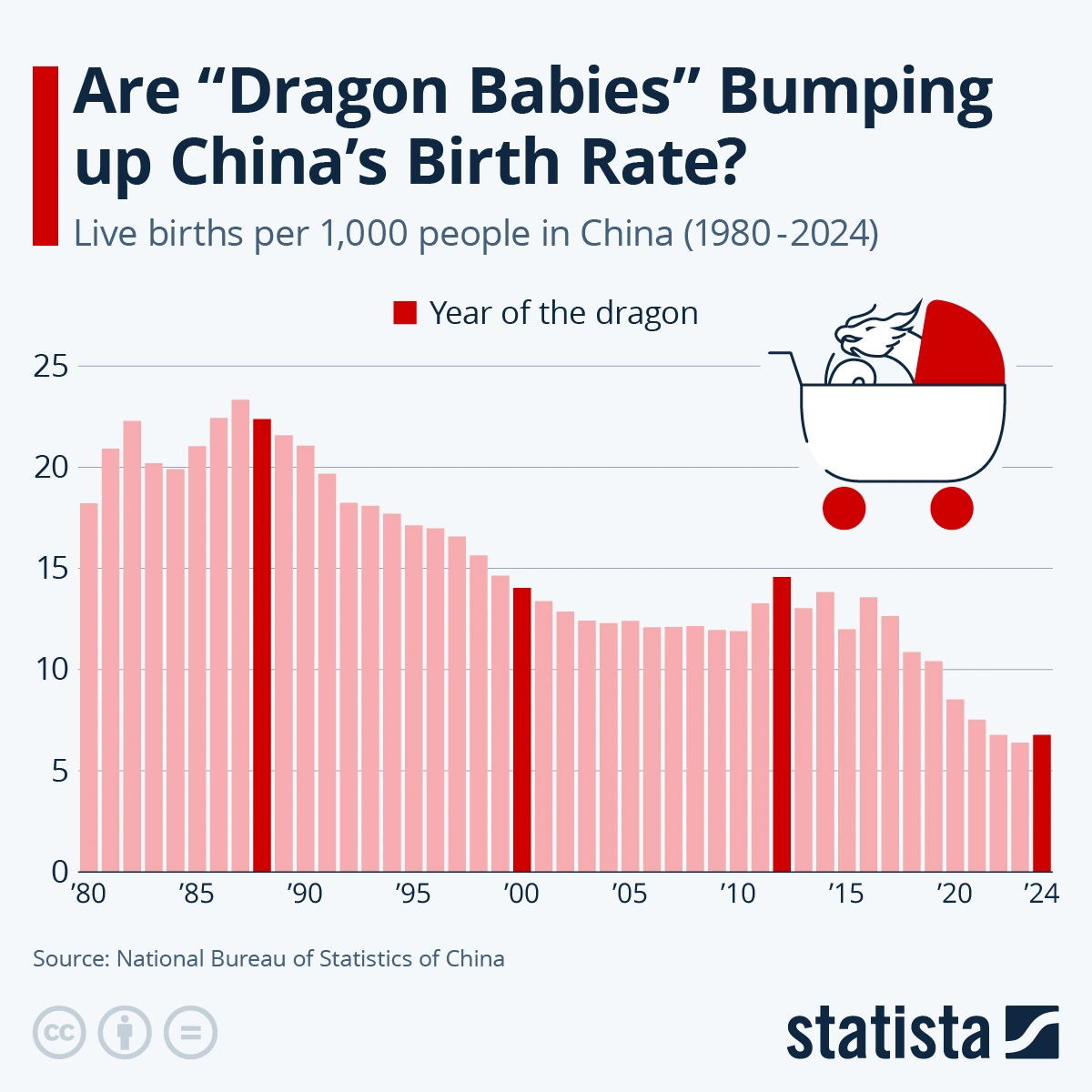

Now, the biggest problem China faces is its collapsing birth rate. Five years ago, China was having 16 to 17 million babies a year. Today, that number has fallen to just 9.5 million—a dramatic collapse. Young people, particularly millennials aged 25 to 40, are no longer getting married or having children.

This is a real problem because if you don’t have children, at some point, you don’t have a country. Addressing this demographic crisis has become the top priority, and boosting confidence is a key part of addressing it.

A lot of what the Chinese leadership is doing today is aimed at boosting confidence. This includes signaling greater openness to foreign investment and cooperation. Why? Because many successful Chinese businesspeople and entrepreneurs have strong connections to the Western world. They sell to Western markets, send their kids to study abroad, and enjoy traveling internationally.

Most businesspeople in China don’t like the idea of China closing in on itself. They want an open China that remains connected to the world. So, when the leadership announces that China is opening up more and is willing to do business with countries like Germany, Canada, or Australia, it sends a positive message.

It’s part of a strategy to boost confidence.

The reality today is very different from when China first opened up to the world in the early 1980s. Back then, China needed Western capital and expertise. China was far behind in industrial processes, management techniques, and other areas. Opening up to the world and forming joint ventures allowed China to gain the knowledge and resources it needed to modernize.

But today, when you look at industries like telecommunications or finance, China doesn’t really need Western expertise anymore. And it certainly doesn’t need Western capital—it has plenty of its own.

So, why is the leadership still pushing for openness when China doesn’t technically need it? The answer is simple: it helps boost domestic confidence. I think everything the leadership is doing right now has to be viewed through this lens. They’re focused on boosting confidence because, once confidence is restored, the economy will improve.

Q6

The China Academy: How much potential do you think Chinese assets have for appreciation? Is now a good time to invest in China’s assets or transfer some money from the U.S. stock market to the Chinese stock market?

Louis-Vincent Gave: I’ve been saying for more than a year now that Chinese equities are where you want to be today.

Here’s how I see it: Chinese equities are still not very expensive. They have massive government support, and bond yields in China are very low. Retail investors are pulling their money out of banks because bank deposits are essentially earning 0%. Meanwhile, a lot of stocks are offering good dividend yields.

The gap between dividend yields on stocks and bond yields is close to record highs. On top of that, you’ve got strong momentum now, following a period of very bad momentum.

If you go through a checklist, it looks very compelling: good valuation, strong momentum, supportive policy environment, and attractive earnings yields. Check, check, check, and check. If you don’t buy now, when are you going to buy?

You could argue that you should wait until the economy is doing better. But by then, as the saying goes, “Bull markets climb a wall of worry.” If you wait, you’ll likely be buying at much higher valuations.

The truth is, you often have to buy when it feels uncomfortable if you want to achieve outsized returns. It never feels good to buy when the market sentiment is down—it feels risky and unpleasant. But that’s exactly when the best opportunities are. If buying something feels good, you’re probably doing it wrong. You might make money over the next three to six months, but you won’t make money over three to six years.

So, yes, I remain optimistic about China.

I genuinely believe China is the most competitive economy in the world. That’s not just an opinion—it’s a fact supported by trade data.

I’m lucky because my job allows me to travel extensively, both within China and around the world. What I see in China today is remarkable. You can stay in very nice hotels for a fraction of what they cost elsewhere. You can have excellent meals for very little money.

For me, China represents one of the most mispriced opportunities out there.

So, yes, I am optimistic about China for the next few years. Over the next two to three years, I think Chinese financial markets will perform very well.

Editor: huyueyue