The Nobel Prize’s Undermining Its Own Value for Underestimating China

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics revealed biases within the award.

Daron Acemoglu, a highly prolific economist, just won the Nobel Prize, but this award seems to have revealed the ideological biases and non-scientific nature underlying the Nobel Prize in Economics.

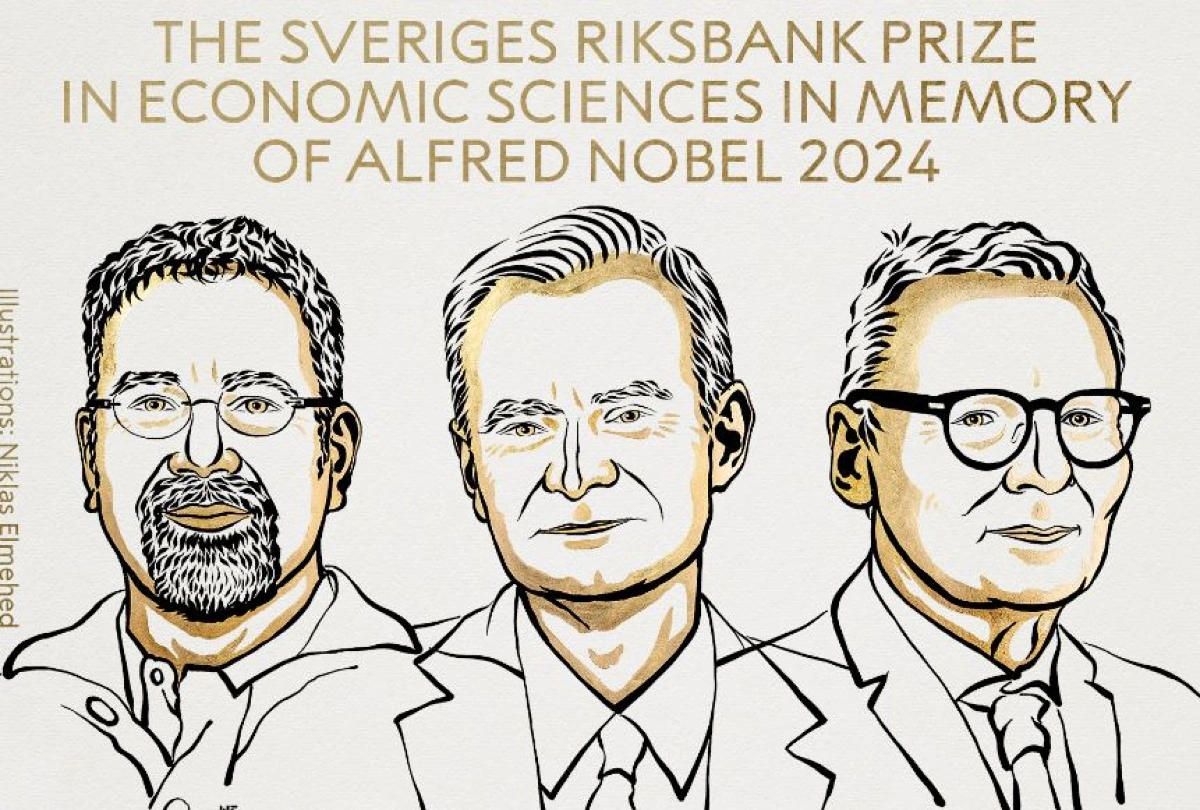

The winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics, Daron Acemoglu is on the left.

The winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics, Daron Acemoglu is on the left.

Acemoglu and his collaborators argue that in their famous 2001 paper, the success of North American economies compared to Latin American ones stems from geographic factors, primarily malaria. They assert that the inhospitable environment in Latin America discouraged white colonizers from bringing their “superior” institutions, resulting in the failure of today’s Latin American countries. In contrast, the favorable geography of North America encouraged colonizers to transplant their institutions, leading to its development into a prosperous region.

We should consider how Indigenous peoples in the Americas view this issue. Today, in the vast populations of North America (the United States and Canada), there are very few Indigenous people, whether pure Indigenous or mixed with European ancestry. In contrast, in Central and South America (Latin America), Indigenous people of mixed European and Indigenous descent have historically made up a large part of the population. For example, in Mexico, mixed Indigenous and European ancestry individuals account for 93% of the total population.

Recent genetic mapping studies of Latin American populations reveal that the predominant mixed-race group, known as mestizos, primarily inherits its paternal genetic lineage from European men, while the maternal lineage mostly comes from Indigenous women.

This indicates that in Latin America, white colonizers not only settled but also extensively interbred with Indigenous women, leading to the replacement of Indigenous male genes. This form of genetic replacement raises questions about whether it is exploitative or inclusive. It can be seen as a cruel form of genocide. What’s more, North American colonizers were even more brutal, systematically exterminating Indigenous populations, resulting in the complete disappearance of Indigenous genes from today’s North American gene pool.

According to Jared Diamond’s “Guns, Germs, and Steel,” Indigenous populations were largely decimated due to their lack of immunity to the diseases brought by European colonizers. However, Indigenous women appeared to possess strong immunity, as they survived and their genes persisted. Furthermore, the mixed-race populations in Latin America seem to have immunity comparable to that of pure European settlers in North America. This raises questions about the genetic adaptability and resilience of Indigenous women, as well as the differing demographic impacts of colonization in these regions.

From the perspective of Indigenous peoples, isn’t the North American colonizers’ “zero tolerance” approach to Indigenous genes less “inclusive”? Could the colonizers’ acceptance of Indigenous women in Latin America indicate that they were less able to establish permanent roots there? Did the intermingling of Latin American colonizers with local Indigenous populations hinder their efforts to instill their home country’s “superior” systems in the Americas?

A colored engraving from 1899 depicting American cavalry pursuing Native Americans.

A colored engraving from 1899 depicting American cavalry pursuing Native Americans.

It’s no surprise that Deirdre N. McCloskey, a prominent American economic historian, commented on Daron Acemoglu’s series of articles by saying:

Acemoglu in short has gotten the story embarrassingly wrong in every important fact.

The significance of the Chinese economic model and the value of New Structural Economics have been seriously underestimated.

After years of rapid growth, China has achieved remarkable success without adopting the colonial models of Europe and Japan, yet this is still severely underestimated by Acemoglu’s New Institutional Economics. I believe that apart from some exceptional elites and politicians in the U.S., the entire West significantly underestimates the significance and value of China’s economic model. Only with the passage of time will the world fully grasp the extent of this underestimation.

I believe that the contributions of Professor Lin Yifu and the ideas of New Structural Economics are still severely underestimated in the global economic community, including among Chinese economists. However, the academic value of Western Economics, especially Daron Acemoglu’s New Institutional Economics, is significantly overestimated in the field of economics.

John Dunn, a renowned historian and political scientist from Cambridge University, once stated:

“In my view, the belief that the economic prosperity of Western countries stems from a particular political system is wrong.”

Lin Yifu is one of the early Chinese economists to criticize the views of Daron Acemoglu and his collaborators after their 2001 article and the book “Why Nations Fail.” I have also long criticized New Institutional Economics.

Lin Yifu was born in Taiwan in 1952 and served as a captain in the army under the island’s authority. In 1979, he swam across the Taiwan Strait to join mainland China, where he later became a renowned economist and established New Structural Economics.

Lin Yifu was born in Taiwan in 1952 and served as a captain in the army under the island’s authority. In 1979, he swam across the Taiwan Strait to join mainland China, where he later became a renowned economist and established New Structural Economics.

The main issue with New Institutional Economics is its misinterpretation of history, as it distorts the causal link between institutions and economic development in the context of European industrialization. This theory wields considerable influence in China, largely because many Chinese economists overlook the industrial history of the West. Western historians, when forced to engage with Acemoglu’s arguments, would likely contend that he has misunderstood historical narratives. However, the Western economic community now almost unanimously praises Daron Acemoglu, as many economists have stopped studying history, particularly the history of Western industrialization, leading to this issue.

For the same reasons, the market reforms in the former Soviet Union failed under the guidance of top American economists, as these economists lacked an understanding of how Western capitalist market economies evolved under the dominance of state power. Lin Yifu pointed out:

“Prominent economists involved in the reforms of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, such as Jeffry Sachs, Stanley Fisher, Oliver Blanchard, Andrei Shleifer, Robert Vishny, Rudiger Dornbusch, Paul Krugman, Richard Layard, and Lawrence Summers, all professors from Harvard and MIT, are considered masters who developed many cutting-edge theories. But why were they unable to predict or explain the challenges of implementing ‘shock therapy’? And why did they have a dim view of China’s economic transformation?”

These masters, including Acemoglu, have significant blind spots and misconceptions about how industrial economies operate in the real world, yet they are idolized by Chinese academic community. Lin Yifu also pointed out:

“Beyond these economists’ insufficient understanding of the history of former socialist countries, the causes of planned economies, and the essential issues of economic system transformation, there are also inherent flaws in Neoclassical Economics when analyzing transformation issues.”

Lin Yifu was the first to identify the inherent flaws in Neoclassical Economics. His background as a Chicago-trained economist demonstrates that he truly possessed a critical spirit during his studies of Western economics.

From Lin Yifu’s books and articles, I have summarized the following three questions:

First, why are the countries that successfully transitioned from developing to developed status, such as the Four Asian Tigers, including Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea, which were once in a period of rapid growth, long been criticized by the West for allegedly breaching market economic rules?

Second, why did those countries recognized as “model students” of market economy by international organizations fail? Examples include Ukraine, Yugoslavia, and Russia, along with many countries in Latin America and Africa.

Third, why has China, which has faced daily criticism from mainstream economists since the beginning of its Reform and Opening-up, achieved such tremendous success?

So far, have any prominent economists attempted to address these questions? Few have focused their efforts here, but I believe these are the types of questions that truly deserve a Nobel Prize.

Acemoglu and his collaborators excel in mathematical and econometric techniques, but they lack major original ideas. Much of their valuable content has already been articulated by predecessors, including Douglass North and Karl Marx. For instance, Marx highlighted the crucial role of the bourgeoisie’s rise in the West’s development into an industrialized nation, suggesting that the West’s acceptance of the bourgeoisie was key to its success:

“The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalized the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

“The barbarities and desperate outrages of the so-called Christian race, throughout every region of the world, and upon every people they have been able to subdue, are not to be paralleled by those of any other race, however fierce, however untaught, and however reckless of mercy and of shame, in any age of the earth.”

American historian Stephen Brown once said:

“From the early 1600s to the late 1800s, militarized monopoly trading companies served as the vanguard and tools of European colonial expansion. They occupied and controlled vast lands and local populations. Behind their commercial success and enormous profits lay various state military and governmental functions and powers. Granting these merchants and companies monopoly control over colonial trade, including military authority, was a cost-effective way to cover the astronomical deficits from colonial ventures and wars.”

However, where Acemoglu attempts to innovate is, as McCloskey points out, filled with errors and misinterpretations of history. Why does the mainstream economics community idolize Acemoglu? Because they do not study Western history, especially the history of modern industrialization. Instead, they simply follow Western economic textbooks and media narratives, which is a significant problem.

The Industrial Revolution in Britain was not due to any outstanding political system.

Acemoglu argues that the British Empire’s economic prosperity stemmed from its establishment of superior political institutions. However, Harvard historian Sven Beckert counters this claim by stating:

“The first industrial nation, Great Britain, was hardly a liberal, lean state with dependable but impartial institutions as it is often portrayed. Instead it was an imperial nation characterized by enormous military expenditures, a nearly constant state of war, a powerful and interventionist bureaucracy, high taxes, skyrocketing government debt, and protectionist tariffs—and it was certainly not democratic.”

The idea that inclusive democratic institutions foster economic prosperity is not something Adam Smith emphasized; it was actually proposed by American scholars after World War II to mislead other nations.

Smith’s concepts of the “invisible hand” and “free trade” were not the reasons behind Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Instead, these were used by the British Empire, which rose to prominence through protectionist trade policies and industrial strategies after supplanting the Netherlands as a manufacturing leader, to deceive less developed countries. The U.S. and Germany were not fooled at that time (as seen in Hamilton’s American manufacturing plan). Although Britain led the way in the Industrial Revolution, it was far from being a free, democratic, or rule-of-law state.

The arguments of renowned American economic historian Joel Mokyr also support this point:

“During the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, British society had little legal order to protect industrial property and human rights. It was rife with theft, robbery, and local uprisings fueled by economic or political grievances… Britain lacked professional police forces until established in 1830, and the court system was cumbersome, expensive, and fraught with uncertainty and injustice. With no official law enforcement mechanisms, the country relied on the deterrent effects of brutal private punishment to maintain order. Over 80% of criminal penalties were executed by the victims themselves.”

A painting depicting gang violence in 19th-century Britain.

A painting depicting gang violence in 19th-century Britain.

Britain initiated its industrialization under such a poor institutional framework, rather than the ideal inclusive system described by Acemoglu in “Why Nations Fail.” Therefore, it is essential to study the real history of Western industrialization, rather than the imagined and portrayed “history” by textbook economists like Acemoglu.

Economics should not only be used to explain the world but also to change it.

The British economist Ronald Coase made an important statement before passing:

“If Chinese economists avoid rigid, preconceived methods in studying economic theory and the practices of market economy in China, they will have a unique opportunity to contribute to the development of economic theory. This task and challenge have become more pressing since the 2008 financial crisis and global economic downturn, to the extent that the next Adam Smith may very well be a Chinese person.”

Lin Yifu has had debates with some prominent liberal economists in China, such as Professors Yang Xiaokai and Zhang Weiying. Lin’s views appear to be more robust in today’s context despite sharp contrast with theirs.

For instance, Yang Xiaokai emphasizes the disadvantages of late development. He argues that developing countries, due to their late start, often need to imitate the West—both in terms of institutions and technology. While technological imitation is relatively easier, institutional imitation poses greater challenges. Consequently, these countries may prioritize technological imitation, which can yield short-term gains but may create long-term vulnerabilities, potentially jeopardizing sustained development. This concept reflects the notion of “latecomer disadvantage.”

In contrast, Professor Lin emphasizes the advantages of late development. He believes that developing countries can leverage their income levels, technological gaps, and industrial structures compared to developed nations. By capitalizing on these technological differences and their comparative advantages, they can accelerate economic growth and technological transformation through participation in the global market and the attraction of foreign investment. This process can, in turn, drive the endogenous development of institutions and management practices that are suitable for the specific conditions of latecomer countries, leading to faster economic progress.

Professor Yang argues that Britain’s success was rooted in the success of its constitutional systems. He points to Japan’s rise as an industrial power through its earnest adoption of capitalist institutions, suggesting that for China to leverage its latecomer advantage, it should promote “institutional development.” Implicitly, this means that developing countries should replicate Western political systems to unlock economic prosperity.

I have just cited numerous historians who argue that Britain did not initiate the Industrial Revolution due to its political system, strong rule of law, or property rights protection. Instead, it was the factors identified by Marx —often overlooked—that gave rise to an economic miracle.

What have we overlooked? The renowned German economist Friedrich List, who extensively studied the secrets of Britain’s industrialization in the nineteenth century, believed that the key to Britain’s rise lay in the industrial policies that it had long formulated and implemented:

“Some believe that Britain’s remarkable rise and continual progress are fundamentally due to the constitutional freedoms enjoyed by its people. However, they might consider how Henry VIII and Elizabeth treated their parliaments. Under the Tudor monarchy, where was Britain’s constitutional freedom? At that time, various cities in Germany and Italy enjoyed far more personal liberties than England.”

“The commercial treaties signed by the British are always oriented towards expanding the market for their industrial products in all countries with which they have treaty relations, while superficially offering benefits in agricultural products and raw materials. What they seek in these countries is to destroy local industries through cheap goods and long-term loans.”

“Once Britain has mastered any industrial sector, it perseveres in nurturing it for centuries like a tender seedling, and then opens its national gate to crush its competitors.”

Lin Yifu argues that institutions are endogenous, meaning that countries must create them based on their historical traditions, economic development levels, and social conditions. He also emphasizes the importance of industrial policy, stating that no developed country has achieved success without relying on it, even though not all industrial policies are correct.

Even though China’s practice has already demonstrated that Lin Yifu’s views are more accurate, he remains a minority voice in the academic community. Despite the widespread promotion of New Structural Economics, he is still seen as a minority figure. The economic community continues to underestimate Lin’s theories, just as the world, especially the West, underestimates China’s economic model.

Lin Yifu often quotes a saying from Marx:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point however is to change it.”

This quote was inscribed on Marx’s headstone.

This quote was inscribed on Marx’s headstone.

His New Structural Economics is essentially “Economic Engineering”—a discipline that can only be learned through practical experience.

He believes that a good economic theory should not only offer a different way to explain the world but, more importantly, possess the capacity to transform it. The reason so many leaders from African countries seek advice from Lin Yifu instead of others is that they recognize his theories on industrial policy can help them alleviate poverty, while the Washington Consensus and Western liberal economics have failed to lift them out of it.

The New Institutional Economics of Acemoglu and the Neoliberalism of Friedman both offer alternative explanations of the world. However, Lin Yifu argues that while their theories may appear logically consistent and can be formulated into mathematical models, they lack the ability to change the world. When imposed on developing countries, these theories often lead to developmental failures and stagnation.

Anonymous

Great analysis Nobel prize are just for colonialist and the people who idolize those evil systems

Anonymous

Nobel prize nowadays is just a theatrical close-door award for whites(western countries) . The prize also name a few to “pity” a few minorities. I don’t think China would count on it. Much less care about the prize anyway.

Anonymous

Excellent!