How to Read the Visible Hand of China

【In our previous interview article, we outlined six key issues from Professor Keyu Jin regarding the U.S.-China trade war, the U.S.-China tech war, and the global trade landscape. If you’re interested, please read more here.】

Q7

The China Academy: When discussing innovation, we must focus on your concept of the “mayor economy” and your new book, The New China Playbook. Could you please introduce how the mayor economy model drives the development of innovative industries?

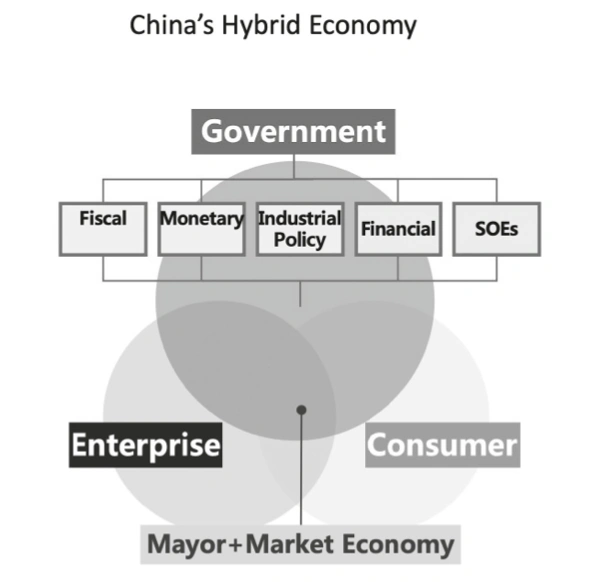

Keyu Jin: Most people think that China is an extremely centralized system, as if all decisions are made from the top down. But that’s a misconception.

A more accurate way to describe it is political centralization coupled with economic decentralization, where the majority of economic policies, decisions, and outcomes are implemented at the very local level. Let me give you an example that really highlights the power and uniqueness of the mayor economy.

Source: The New China Playbook by Keyu Jin

Source: The New China Playbook by Keyu Jin

First of all, why are mayors, party secretaries, provincial governors, and other local government officials so motivated to do the right thing for the economy? You might assume that a country like China, without a Western-style democracy, would be more prone to having a “grabbing hand” approach. But instead, local government officials often have a “helping hand.”

I’m currently in China, observing how local governments actively coordinate between lenders and debtors, between banks and companies. They are setting up programs to attract talent, providing one-stop services for businesses, and going out of their way to help. Why do they have this incentive to offer a helping hand rather than a grabbing hand, as most people might think?

There are a few key reasons. The most important one is that if they do a good job with the local economy, they get promoted. There’s personal gain, glory, a sense of accomplishment, and even envy from competing governors or party secretaries in neighboring regions. This competitive dynamic motivates them to, by and large, do the right thing.

This is something people often misunderstand about China—they assume the state is always in opposition to the private sector, but in fact, the state often enables the private sector. Of course, there are instances where the state crowds out the private sector or monopolizes certain industries. But overall, China’s rapid economic growth has relied heavily on this mayor economy and the decentralization that allows local governments to play a significant role. Why is this necessary? Because not everything in China’s system is fully mature. Rules, permits, and the business environment often require some level of government intervention.

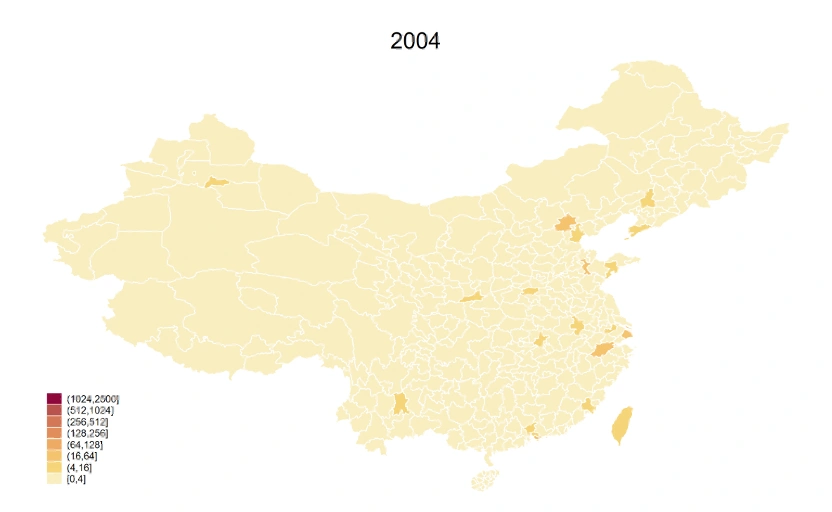

Let me give you a specific example to illustrate the mayor economy’s power, combined with the effectiveness of industrial policy. Take solar panels: in 2005, if you looked at a map of China, solar patents and production were virtually nonexistent — a “desert.” That year, the Chinese government decided to implement industrial policies to support solar panel development.

Source: Banares-Sanchez, Ignacio, et al. “Chinese Innovation, Green Industrial Policy and the Rise of Solar Energy.” (2024)

Source: Banares-Sanchez, Ignacio, et al. “Chinese Innovation, Green Industrial Policy and the Rise of Solar Energy.” (2024)

But instead of a top-down nationwide approach, these policies were implemented at the local level—starting with four cities, then expanding to ten, then twenty, and eventually forty cities over time.

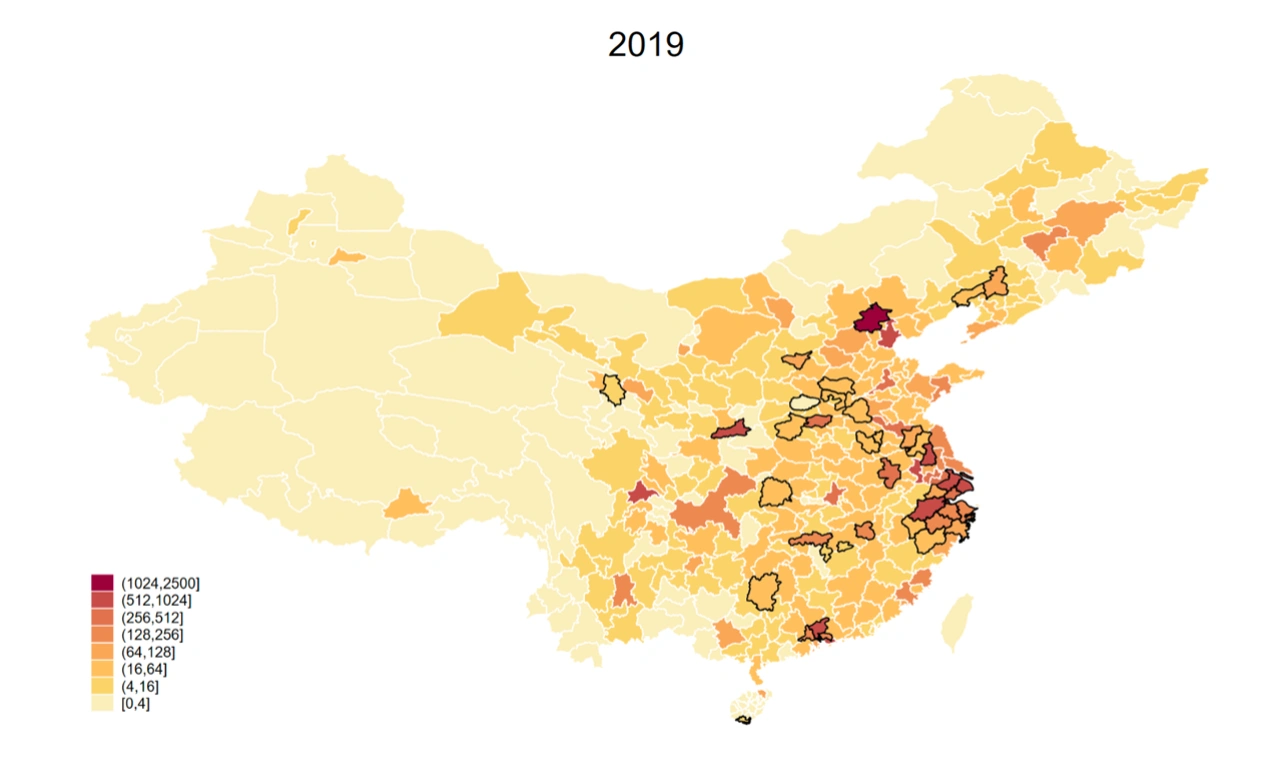

Fast forward to 2015: if you look at the same map, solar panel production and innovation had blossomed across China, except in some western and central provinces. It wasn’t just concentrated in major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, but spread across many regions. Some cities were filing thousands of solar panel patents every year, with local governments playing a crucial role in implementing industrial policies.

Source: Banares-Sanchez, Ignacio, et al. “Chinese Innovation, Green Industrial Policy and the Rise of Solar Energy.” (2024)

Source: Banares-Sanchez, Ignacio, et al. “Chinese Innovation, Green Industrial Policy and the Rise of Solar Energy.” (2024)

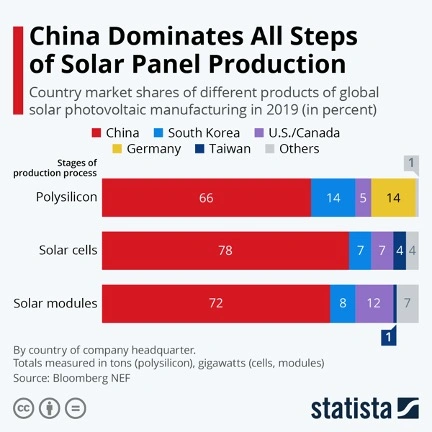

The same can be said for electric vehicles (EVs). Within a decade, China became the largest producer of EVs and EV-related patents in the world. This rapid growth is almost incontrovertibly the result of the combination of the mayor economy, industrial policy, and private entrepreneurship. These factors created new, strategic industries in record time—something no other country has achieved so quickly.

That said, the mayor economy also has its downsides. Everything has costs and benefits, and one has to weigh the overall outcomes. For example, local governments’ incentives sometimes lead to misallocation of resources. This can result in excessive capacity for EVs and solar panels, or rising debt levels at the local government level. The focus is often on supply-side production, rather than demand-side consumption. The ultimate goal of the mayor economy is to champion the best companies and create global leaders, but this sometimes comes at a cost.

Finally, I want to clarify that industrial policy is not just about subsidies. Many countries misunderstand this, assuming that throwing money at a sector will guarantee success. That’s not the case. Industrial policy involves much more: creating a good business environment, coordinating supply chains, and jump-starting new ecosystems. For example, local governments might procure new technologies via state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to create initial demand. They ensure the industry has the right players and environment, mobilizing, coordinating, and allocating resources effectively.

Ultimately, the success of industrial policies depends on whether they lead to more competition. In China, industries like EVs and solar panels are experiencing ferocious competition. Industrial policies haven’t created a few monopolistic winners; instead, they’ve fostered broader market competition. Once the market matures, the policies are withdrawn, and the market determines the winners.

Q8

The China Academy: I’m curious about why countries like Germany and Japan are lagging behind in the EV industry.

Keyu Jin: That brings us to China’s inherent advantages. The state plays a critical role in new strategic, emerging sectors—industries that need a boost or a jump-start. If you wait for the private market to do it, it will either be too slow or insufficient. Private investment alone won’t be enough, especially where market failures exist.

China’s success lies in its state’s ability to mobilize and coordinate resources. But it also lies in its natural advantages: a huge market, rapid learning-by-doing, and fast customer-product feedback loops. Many European companies have said they need a presence in China because the ferocious competition here helps them refine their products. The fast feedback loop between customers and companies ensures they know what the ultimate prototype should be.

Additionally, China has a vast number of engineers and significant financing available to create new sectors. However, there’s a critical issue: China is excellent at production and innovation, but not as strong in consumption.

Q9

The China Academy: I’d like to return to your earlier point about local competition. You mentioned that local competition is crucial to China’s economic development. But with economic power decentralized to local levels—even back to the early days of New China—why is local competition so significant in China’s economic model compared to other capitalist regimes?

Keyu Jin: Local competition among provinces, regions, or cities creates an inherent system of checks and balances. Think about it this way: if you’re a promising company setting up in a city, and the local government is unfriendly, corrupt, or extractive, what do you do? You simply relocate to a neighboring province or city, contributing to their GDP, investment, and employment instead.

Local governments care deeply about these metrics—GDP, employment, and economic contributions—because these determine their success. Killing the goose that lays the golden eggs would be counterproductive.

If there’s no competition, this dynamic breaks down. But in China, competition among local governments is fierce. For instance, we’ve seen intense bidding wars among cities to attract EV companies like NIO. I recently spoke with a startup that received offers from both Beijing and Shanghai. The Beijing government promised to match and even exceed Shanghai’s offer—even though the company was still in its early stages.

This competition constrains local government behavior. Contrary to misconceptions, local officials in China face significant checks and balances, including monitoring from civil society. Social media, for instance, is filled with dynamic debates and criticisms of local governments. A study by Harvard’s Kennedy School found that over one-third of social media posts in China are about monitoring local government officials.

So, while there’s a lot of misunderstanding about China, local competition within its political system serves as an important mechanism of checks and balances.

Q10

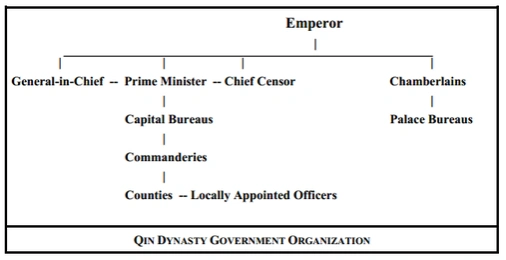

The China Academy: You also mentioned that the current political economy regime is linked to ancient China’s historical political traditions, right? Can you elaborate more?

Keyu Jin: China has thousands of years of history. In fact, it created one of the first modern bureaucracies. There are vestiges of this tradition and historical elements in China’s system today, including the horizontal and vertical stretches of governance that reach every stratum of society and every corner of the country. This includes the nuanced relationship between the central and local governments—akin to the emperor’s role in implementing policies at the local level and monitoring what was happening across a vast nation.

This central-local dynamic, or tussle, is a millennia-old feature that remains a core characteristic of China’s political economy today. Even when addressing topical issues, such as local government debt, it all comes back to this nuanced central-local relationship: how much responsibility and resources should be given to local governments? How much monitoring is needed? Should the central government worry about moral hazard when bailing out local governments? If irresponsible local governments are bailed out, those that behave responsibly may feel unfairly treated.

These dynamics are critical to understanding the most important economic outcomes in China today. Historical traits such as bureaucracy, the relationship between authority and the people, and the balance of power between central and local governments continue to shape the system.

The West often frames the relationship between the Chinese government and its people as tense, supposedly due to authoritarianism. But in reality, the relationship with authority in China is characterized by quiet deference, though not blind submission. This dynamic has been a permanent and pervasive feature throughout history and across society—whether it’s the relationship between teacher and student or parent and child. This concept of authority is fundamentally different from that in the West, and I think people should adopt a more open-minded view about these differing perspectives.

Q11

The China Academy: You once made an interesting observation: in China, policies change frequently, but the ruling party remains the same. In contrast, in the US, parties change, but policies remain consistent. Why is it that China’s policies can change so drastically, sometimes shifting to a new model overnight? Where, then, can we find its predictability?

Keyu Jin: China’s rapid pace of change fits its status as a developing country, where steady-state maturity—whether in the business environment, rule of law, or financial system—has not yet been fully achieved.

For developing countries, faster progress is often better. Sometimes, the ability to implement strategically important policies without too much political debate or constraint is an advantage. This has led some studies to conjecture those non-western-style democracies might accelerate growth under certain conditions and at certain stages of development.

Without delving into that debate, I think China’s system is far more nuanced than simply “being able to change policies quickly.” What makes it unique is its ability to start a policy, reform, or radical idea in one small area. If it fails, it’s discarded. If it succeeds, it’s gradually rolled out to five provinces, then ten, and eventually the entire country. This is how reforms have been implemented and how they’ve succeeded.

China’s approach contrasts sharply with that of many transitional countries, such as those in Eastern Europe, where overnight changes—like the “Big Bang” approach—often led to unexpected consequences. In contrast, China pursued gradual reforms and policy development strategies. Even today, when significant paradigm shifts are needed, China adjusts. Once the government makes a decision, it can avoid prolonged traps by acting decisively.

That’s not to say there haven’t been policy errors in China—there certainly have been. Sometimes these errors aren’t recognized, or aren’t addressed quickly enough, leading to problems.

It’s also difficult to compare China with a country like the US. The US is already at a steady-state level of development, where improvements are incremental and gradual. In the US, the political system allows for debates over policies and imposes restrictions on what can be done, which is entirely appropriate for its context.

But the key difference is that the Chinese government has a long-term vision. It can afford a longer horizon for planning. In many aspects, China’s leaders think in terms of 20 or 30 years because of policy continuity. There are no pendulum swings or deliberate disruptions caused by party politics or competition. If radical change is necessary, there is political space to implement it—whether or not it’s ultimately pursued is another matter.

Q12

The China Academy: You also mentioned challenges in governance. Previously, China focused solely on economic indicators, but now considerations include environmental protection, innovative industries, and social stability. Some of these goals may even be contradictory. Will this pose a challenge to the existing political economy model?

Keyu Jin: China’s challenge is that it has shifted from a singular focus on economic development—encapsulated in GDP growth as a quantifiable goal—to a broader set of objectives that include social and national security goals. When the objective function becomes multivariate, achieving the desired outcomes becomes much more difficult under the current system of competition and governance.

This is indeed part of China’s challenge today, but ultimately, it’s also a matter of choice and preference, which can differ from country to country.

For example, the US excels in trailblazing innovation but scores poorly on inequality and other social indicators. Meanwhile, Europe performs better on social aspects but lags in wealth creation and innovation. Where does China want to position itself? Does it want to emulate the US’s decentralized economy and innovation, despite the associated social problems? Or does it want to resemble Europe?

This is part of what I call China’s “new playbook,” which aims to find a combination that suits its national characteristics.

I believe that China should unleash wealth creation at the individual, micro level. With that wealth, better political mechanisms could be developed to redistribute resources in ways that avoid the pitfalls seen in the US. Without wealth creation, there’s little to work with.

Over the past 40 years, the Chinese people have been deeply grateful for reforms and economic progress. That’s what they value most. Of course, this path has included turbulence, inequalities, and massive wealth accumulation among a few individuals. But China is a large country, and this is almost a reflection of meritocracy—where a good idea can turn someone into an overnight billionaire.

Addressing inequality is something China can work on. Unlike the US, China doesn’t have a lobbying system that exacerbates inequity and unjust outcomes. It can prevent that. However, it shouldn’t give up on its pro-growth agenda. China is one of the few places in the world where massive wealth creation is still possible, and that dream—and reality—should not be abandoned.

Q13

The China Academy: You discussed a lot about China’s high savings rate in your book. Is there an inherent connection between real estate being a pillar industry in China, high savings rates, and sluggish domestic demand?

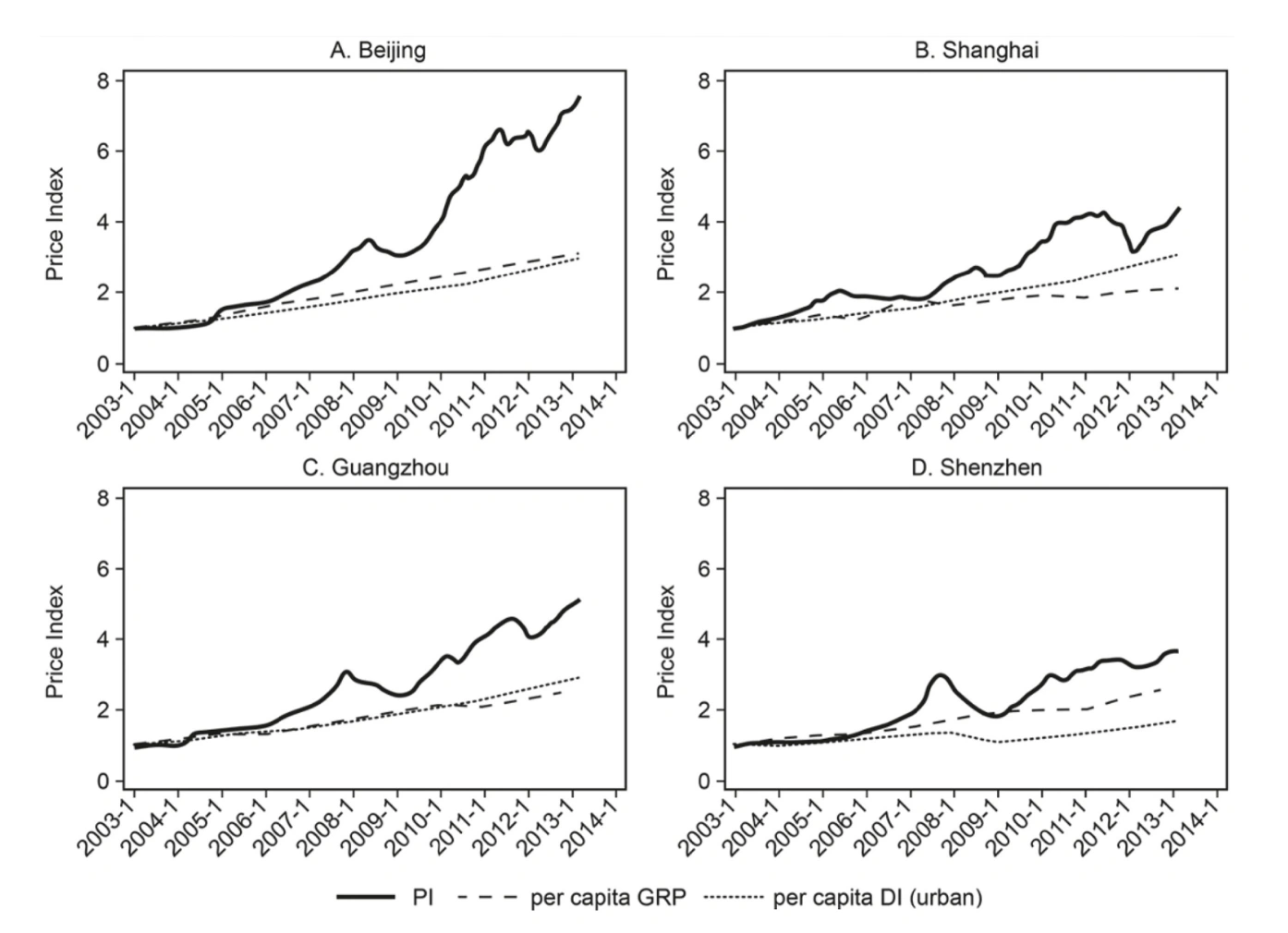

Keyu Jin: I think people tend to overlook one important fact about China: real estate is not just a property sector that accounts for roughly 30% of GDP. One of the deeper structural issues is that real estate in China functions as a quasi-financial and shadow fiscal system.

Source: The New China Playbook by Keyu Jin

Source: The New China Playbook by Keyu Jin

This is a very unique attribute of China, unlike the US or Japan. There’s really very little comparison here. Real estate companies in China essentially acted like financial systems—they generated credit, created liquidity mismatches, and played a financial role. At the same time, local governments relied on land and real estate as collateral to secure financing or depended on land sales revenue to fund local projects.

These two systems—real estate and local government financing—became tightly intertwined. When the real estate sector encountered trouble or the bubble began to deflate, it caused cascading problems. It created liquidity issues in the financial system and put immense strain on local governments. Local governments now have very limited resources to carry out their roles in the political economy or the mayor economy model.

This debt overhang also affects consumer demand, as most household wealth in China is tied to real estate. This is, in my view, one of the fundamental reasons for sluggish economic growth in China today.

Part of China’s high savings rate—a phenomenon that many try to explain—is related to real estate. People save to afford properties that are extremely expensive. However, this is only part of the story. Growing inequality and the lack of diversified financial channels also contribute to the high savings rate. There aren’t many investment instruments in China that offer a good risk-adjusted return for households, aside from real estate.

Q14

The China Academy: Can the younger generation in China help transition to a consumption-driven economic model?

Keyu Jin: If we look at generational shifts in China, they are significant actually radical. The younger generation values lifestyle and work-life balance much more than older generations. They are less willing to work long hours or take on multiple shifts just to earn extra money.

Instead, they love to enjoy life, spend money, and even borrow. This marks a sea change in mentality.

In this sense, I think it’s important to give the country time to transition and break free from the previous mindset. Older generations grew up saving for a rainy day. They ate meat maybe once a month during their youth and developed a mentality of frugality and caution. For them, saving was essential for survival.

The younger generation, however, is more willing to embrace the idea of spending ahead of future income. They see their salaries rising and are more comfortable borrowing against their expected future earnings. This is an entirely new mindset, but I think the younger people are ready for it and can play a key role in shifting the economy toward consumption.

Q15

The China Academy: China’s new generation has not entirely aligned ideologically with the West and tends to preserve its own cultural traditions. This might be unexpected for the West. What impact does this have on ideological struggles in global politics?

Keyu Jin: The new generation—whether in China, the US, or Europe—is more connected than ever through social media and new technologies. They share common challenges left behind by previous generations or challenges that older generations cannot solve.

This connectivity creates opportunities for collaboration. When faced with shared global challenges, rather than relying on past successes, there’s more potential for cooperation.

Millions of Chinese students have studied abroad, and many have returned to China, contributing to its development while serving as a bridge between East and West. Their outlook is different—it’s not about “winning” or “dominating.” They care about issues like the environment, social justice, animal rights, and inequality.

This reflects a cycle of renewal in a country transitioning from poverty to prosperity. As a society becomes wealthier, its values and priorities naturally evolve. The new generation in China embodies this change, with moral and ethical values that are increasingly global rather than strictly Western or Chinese.

Q16

The China Academy: You mentioned in your speech that the Chinese economy has not experienced a recession in the past 40 years. You suggested that some decline may be beneficial to clear out obsolete enterprises. What are your expectations for China’s economic development in the next decade?

Keyu Jin: What I was referring to is that natural booms and busts, or business cycles, are normal features of market economies—but they’ve largely been absent in China.

One could argue that there was a recession after 2015, but to some extent, it was stalled by the Chinese government.

Natural cycles, like recessions, aren’t necessarily bad. They help weed out unproductive firms and create space and resources for new companies. This is the “creative destruction” aspect of market economies that should be embraced. It’s also a learning process for an economy, much like the stock market. Overprotecting retail investors, for example, may shield them in the short term, but it prevents them from learning how to make informed decisions and manage risks.

Small cycles are less costly than major crises after long periods of stagnation. So my argument is that these natural cycles should be allowed to occur.

Looking at China’s economy, I would caution against terms like “peak China” or “game over” simply because of a slowdown or recession. The US has had 12 recessions in the past 100 years—this is perfectly normal. However, if cyclical problems aren’t addressed with the right tools and commitment, they can become long-term structural issues.

China’s current challenges started with aggregate demand deficits and other cyclical problems. If these aren’t dealt with properly, they could evolve into more persistent economic challenges.

Q17

The China Academy: Your book encourages us to look beyond the binary thinking of socialism versus capitalism when analyzing China. However, in recent years, we’ve witnessed ideological tensions, such as restrictions on internet giants. These moves have raised concerns among private sector participants, including foreign investors. How should we view these contradictions?

Keyu Jin: China isn’t fixated on one set of policies. As we’ve discussed, if a policy isn’t working, the government will adjust.

You’ve seen this before—policy shifts and pendulum swings happen in China. I wouldn’t fixate on a single ideological framework, because if a policy leads to major issues like unemployment or stagnation, China will change course.

In recent years, I’ve argued that pragmatism will return, and the focus will shift back to economic priorities. If policies are seen as harmful to living standards or economic growth, adjustments will be made.

Right now, discussions in China are largely about economic policies—how much stimulus to apply, and when. These debates are not ideological; they’re practical. There’s also a notable return to economic pragmatism.

For investors, it’s important to do real homework and look beyond the headlines. If you’re investing in China for the long term, you need to analyze companies’ operational, strategic, and financial conditions. Despite challenges, China still offers many advantages compared to other emerging markets.

Editor: huyueyue

Anonymous

Please delete my previous comments in other posts, they are in error. I own up to my mistake but ignorance is never a excuse, apologies.

Light.