A Recession Is Not Always a Bad Thing

In an interview with CA, we discussed 17 key questions on China and the global economy. This article highlights six global predictions, with more on China’s political economy coming soon.

Q 1

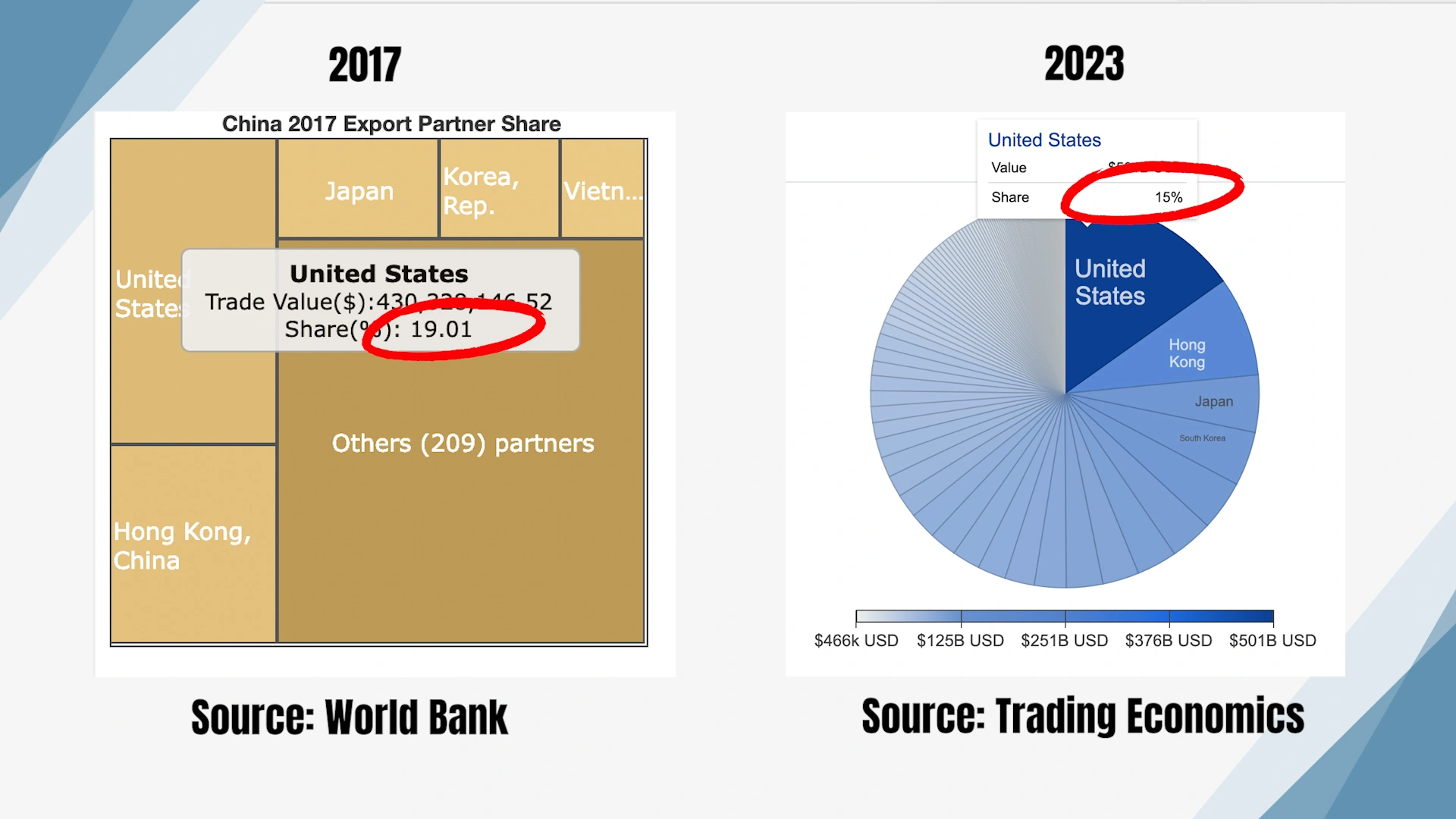

The China Academy: After Trump’s reelection, despite his threats of imposing taxes on China, the Chinese capital market seemed relatively calm. Trade data shows that by the end of October 24, China’s export dependency on the United States decreased to 14.6%. Can we say that the US has failed in its trade war with China? What changes have occurred in China’s foreign trade pattern in recent years?

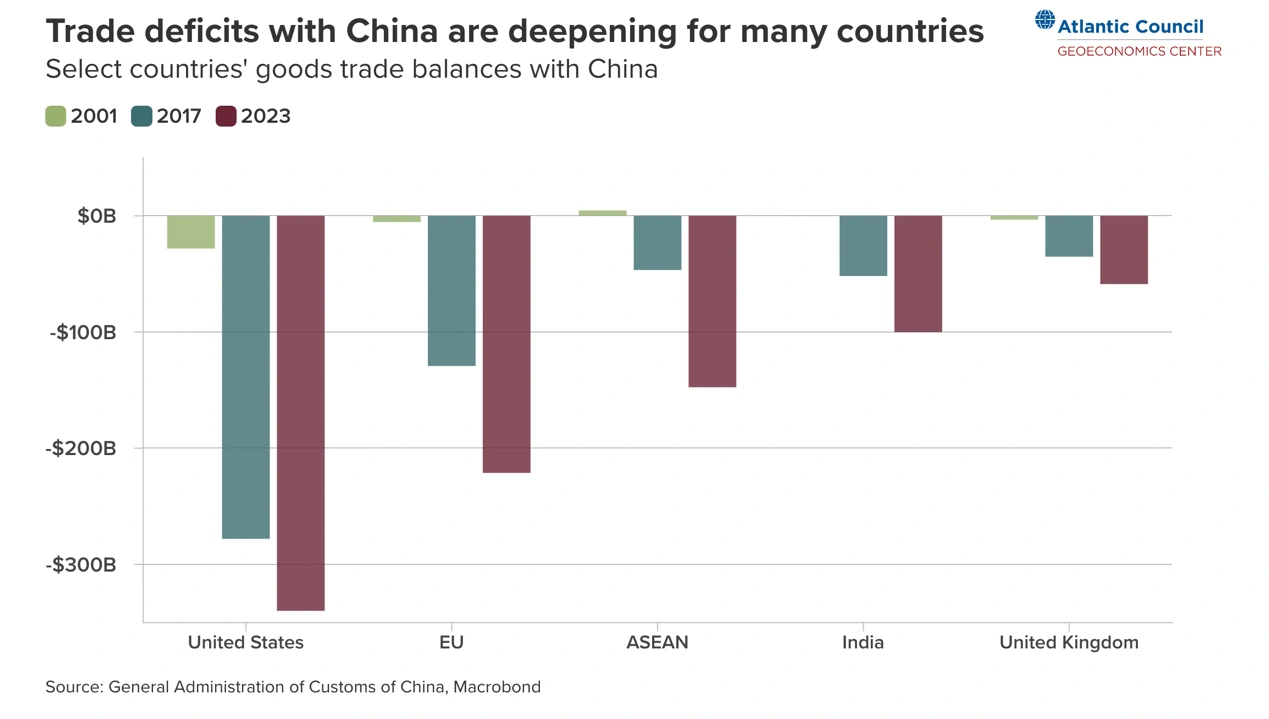

Keyu Jin: I think that the objectives of the US trade war, whether it was to reduce Chinese exports to the US and thereby reduce the bilateral deficit or to mitigate China’s global position in manufacturing, in that sense, have totally failed. And I think most economists would agree that trade wars really accomplish very little, except to hurt the countries involved. But I think going beyond that, there are also unexpected consequences, which is that it’s really been a long march since the first trade war, where Chinese companies have already been braced for this new uncertainty.

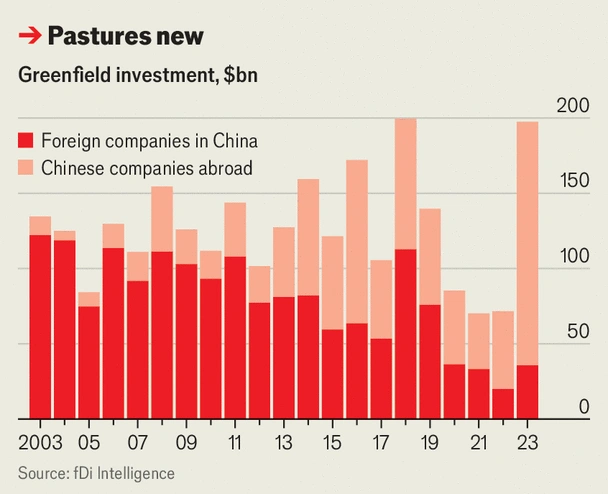

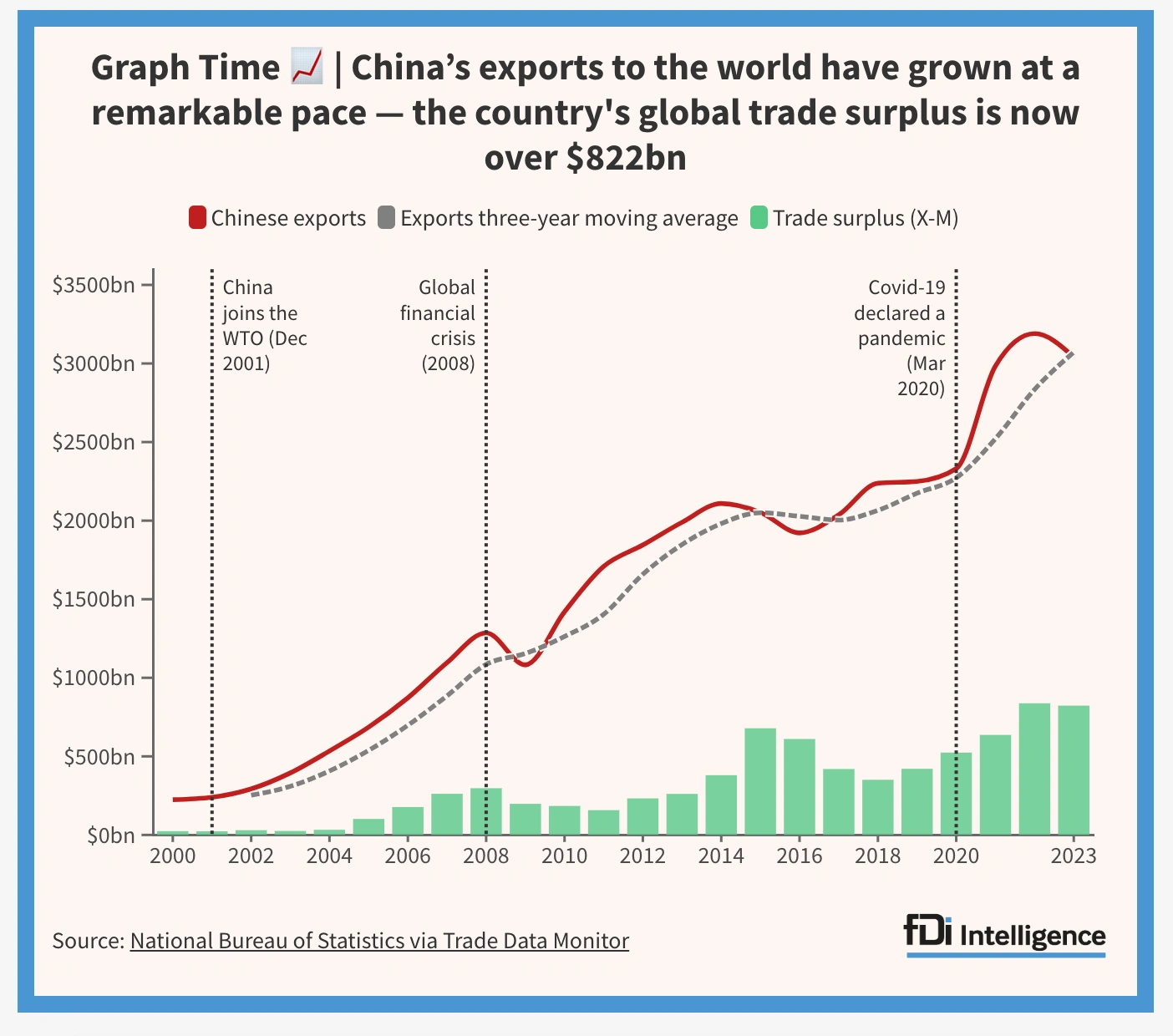

It has set off a globalization frenzy among Chinese companies. If you look at the data, in many major sectors, the majority of these Chinese companies have either already considered or are already implementing “going global” plans that would not have taken place as rapidly had there not been, for the first time, a trade or tariff war.

Moreover, if you look at the data, Chinese exports really seamlessly flowed away from the US to other countries. That is why currently Chinese exports are back at pre-tariff war levels. Chinese exports as a share of global exports have actually even climbed up. Meanwhile, the US share is declining, which means that China is even more integrated into the global economy.

In the past, I think for all of these tactics or strategies or restrictions, there are always unintended consequences to consider. China is not a place where they would voluntarily just submit to these aggressions but would actually react to it. And whether in the end the overall impact was beneficial for the US or not, I think it’s really the contrary.

Q 2

The China Academy: What are your practical predictions for the economic actions of both China and the US in Trump’s potential second term?

Keyu Jin: It is not clear what President Trump would do with regard to imposing tariffs on China when he becomes president again. I think all of that is still very much in flux. But what I’m certain of is that China is not interested in a trade war.

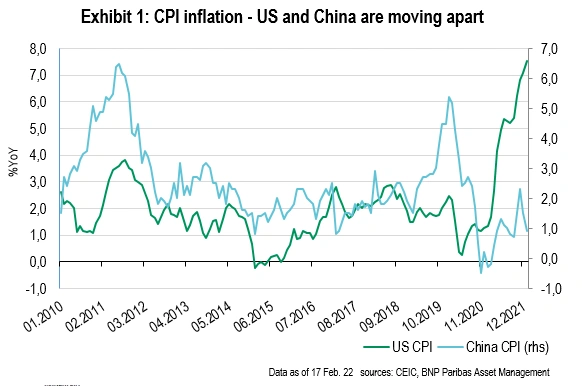

China is not interested in engaging in more economic or financial confrontations with the United States for one reason, which is that it’s not going to be good for China. It’s not going to be good for the US either. Also, inflation is at a much higher level than it was in 2018. The Chinese economy is also in a weaker position than it was in 2018. The majority of China’s economic challenges remain within the country. It’s internal, not external.

The focus of China is not on the US, contrary to the other way around. There is no dangerous obsession with the United States in China, unlike the dangerous obsession with China in Washington, D.C. To fix China’s economy, they have to direct more of their resources internally.

Moreover, we’ve heard multiple times in the last couple of months the premier saying emphatically that China is going to be the world’s opportunity, meaning China is going to open up widely, deeply, broadly, and even unilaterally if needed. China is going to impose zero tariffs on the least developed countries.

That is a symbolic gesture of a big country trying to be part of a global story, trying to really lift up other countries in the network as well.

Q 3

The China Academy: And the technological competition between China and the US is a crucial topic in their relationship. Quoting a former Google CEO, Eric Schmidt: “In our lifetimes, a battle between the US and China for knowledge supremacy is going to be the big fight.”

You have also mentioned that for the first time in history, China, as a developing country, is creating cutting-edge technology despite the US technology blockade. Why Has the U.S. Technology Blockade Against China Been Ineffective?

Keyu Jin: Again, there are unintended consequences and reactions to every action put forth. I’m not sure if, historically, sanctions, restrictions, export controls, or any kind of barriers to another country’s progress have ever worked. In fact, most of the time they backfire. Look at the Spanish blockade of Portugal in the 16th century.

Portugal ended up building an entire navy force—thanks to the blockade. There are so many other historical episodes where cutting off resources turned a goal into a national program. These efforts tend to accelerate progress.

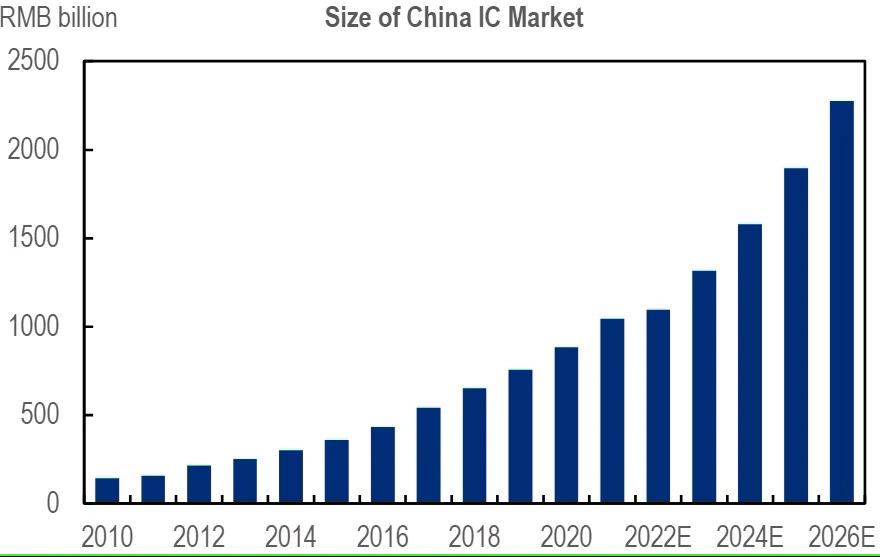

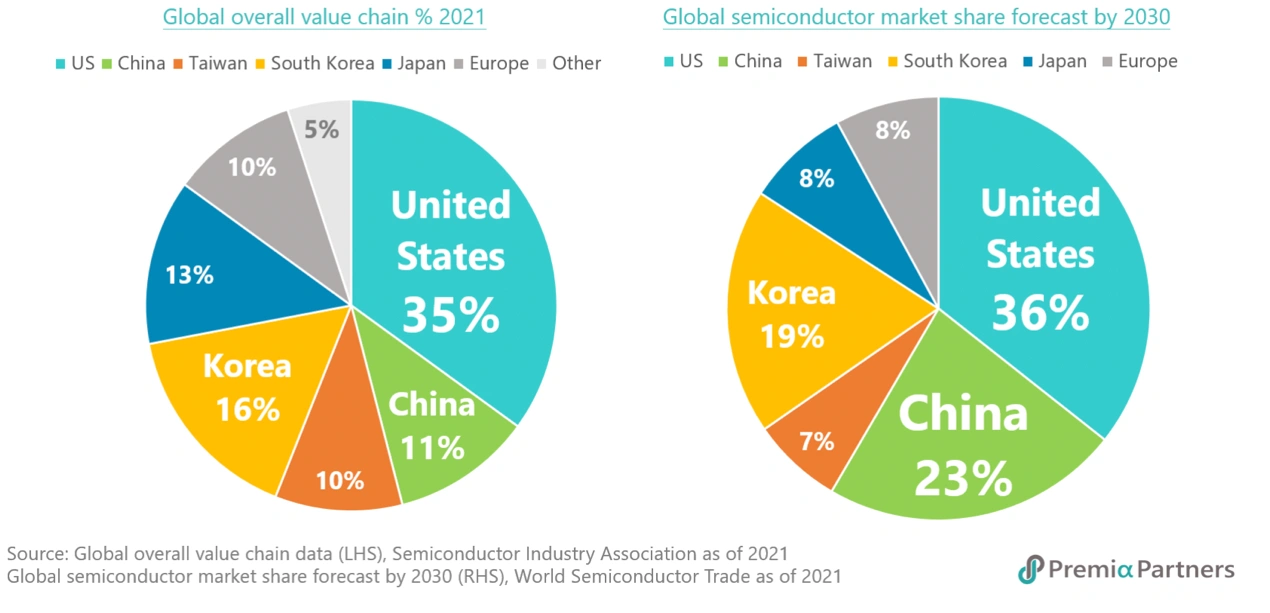

We’re seeing some of that in China. For sure, there has been a massive reaction to the technological restrictions. Take semiconductors, for example. China used to comfortably import them, as much in value as it did oil. Now, all of that demand is being redirected to domestic companies, which are seeing more profitability, greater capability, and more scope to invest in research and development. This is really pushing them—forcing them—to accomplish something they didn’t need to achieve before.

There are so many other examples that follow a similar pattern. Unlike trade and investment, where there is often scope for back-and-forth, tit-for-tat negotiations and normalization to a certain extent, technological developments are happening in parallel ways.

But if you look at China, it’s not just the US that it can work with. It has a huge market in developing countries, and it is actively selling to Europe.

Especially with Trump’s potential presidency and the possibility of weakening US ties with its allies in Europe, there is an opportunity for China to strengthen, reinforce, and create new relationships. That’s one thing the US-China trade war has accomplished: a new trading system and a new globalization network. And this network is not static—it’s dynamic. When one channel, like US-China trade, is shut off, other pieces are reshuffled and realigned.

We’re seeing many countries around the world, against the backdrop of US-China competition, signing new trade agreements, building new trade partnerships, and reinforcing regional trade ties.

China is doing the same. There’s a reshuffling and dynamic optimization, if you will, of trading, financial, and technological networks. Because in the end, it is no longer just the US and China in this world—it’s truly a global economy.

But most importantly, the internal drive in China has never been higher. You have an entire nation pushing for cutting-edge technology. This effort comes from the top-down, with central government initiatives, but also from the bottom-up, with local governments working alongside private sectors and entrepreneurs. The private entrepreneurs, who are the driving force of innovation, are being given more opportunities and are being forced to achieve more.

Now, do I think that overall this is a good thing for the US in the long run? Absolutely not. The world is much better when technology can, to some extent, be shared for the advancement of the entire global economy.

But in this context, you can’t simply stop a rapidly developing, large nation with a vast number of engineers, hardworking people, and significant market access. It’s not possible to stall it. In fact, such actions may spur them to achieve even more.

Q 4

The China Academy: Things have changed—the tables have turned. In the past, China used its market to exchange for foreign technology transfers. But now, we could say that in Europe, when we do EV investments, European countries are asking for our technology transfer.

Keyu Jin: There’s a great deal of irony here. When I was writing my book, the discussion was still about technology transfers that Chinese companies demanded from international companies.

Now, as you’ve said, the tables have completely turned. What’s China’s response? First of all, the Chinese government’s response is to let the companies decide. If it’s a mutually beneficial arrangement, they will go ahead with it. That’s up to them—it shouldn’t be imposed top-down by the government. This is economics, this is capitalism: trading one thing for another, like trading technology for market access.

Chinese companies understand that very well. They’re not the first to say no to such arrangements. For example, in the EV sector or batteries, some Chinese companies are heavily investing in Europe. They’re setting up factories, forming joint ventures, and shifting some production and research centers to Europe—not the US, by the way, but Europe. And that’s good for both Chinese companies and Europe.

I think that with these technological advancements, it’s important to maintain a certain edge—a kind of monopoly power—for a limited time. This induces entrepreneurs to innovate, to invest their time and resources into creating something whose profits or benefits they can reap for a certain period. But that advantage isn’t forever, right? That’s just how it typically works.

Q 5

The China Academy: You mentioned in your speech that the Chinese economy has not experienced a recession in the past 40 years. You suggested that some decline may be beneficial to clear out obsolete enterprises. What are your expectations for China’s economic development in the next decade?

Keyu Jin: What I was referring to is that natural booms and busts, or business cycles, are normal features of market economies—but they’ve largely been absent in China.

One could argue that there was a recession after 2015, but to some extent, it was stalled by the Chinese government.

Natural cycles, like recessions, aren’t necessarily bad. They help weed out unproductive firms and create space and resources for new companies. This is the “creative destruction” aspect of market economies that should be embraced. It’s also a learning process for an economy, much like the stock market. Overprotecting retail investors, for example, may shield them in the short term, but it prevents them from learning how to make informed decisions and manage risks.

Small cycles are less costly than major crises after long periods of stagnation. So my argument is that these natural cycles should be allowed to occur.

Looking at China’s economy, I would caution against terms like “peak China” or “game over” simply because of a slowdown or recession. The US has had 12 recessions in the past 100 years—this is perfectly normal. However, if cyclical problems aren’t addressed with the right tools and commitment, they can become long-term structural issues.

China’s current challenges started with aggregate demand deficits and other cyclical problems. If these aren’t dealt with properly, they could evolve into more persistent economic challenges.

The China Academy: Why did the US engage in aggressive money printing and liquidity measures after the pandemic, while China’s fiscal and monetary policies remained relatively conservative? Why is there such a stark difference between the financial policies of the two major economies?

Keyu Jin: The Chinese government faces a major dilemma that US policymakers don’t: how to stimulate growth without exacerbating debt problems.

After 2015, China’s primary objective was to cool down an overheated economy, which led to monetary tightening. Today, the challenge is reversed: how to heat up an economy that remains sluggish. But this must be done carefully to avoid piling on more debt, particularly at the local government level.

Another reason for China’s caution is uncertainty about what policies will work most efficiently. There are many potential tools: fiscal and monetary coordination, support for real estate developers, direct consumer stimulus, or service-sector incentives. The challenge is ensuring that these measures translate into real economic activity, rather than just being absorbed into the financial system or used to reduce local government debt.

Conceptually, there’s also a key difference: the Chinese government believes that sustainable wage increases are essential for long-term consumption growth. Temporary stimulus measures, like the “hand-to-mouth” checks in the US or short-term “revenge spending,” are seen as insufficient to drive lasting changes in consumer behavior in China.

While I believe some Keynesian-style effects could work, the Chinese government—and many others outside the US and UK—are hesitant to pursue large-scale Keynesian stimulus. This reflects a fundamental difference in mindset.

Q 6

The China Academy: China is actively participating in and shaping a new global economic order, including initiatives like BRICS cooperation, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). How do you view China’s efforts in building this new order?

Keyu Jin: The world is becoming increasingly multipolar. Some see it as bipolar, dominated by the US and China, while others see a multipolar world where India, Russia, Europe, and emerging markets play significant roles.

China’s approach has been to make as many friends as possible, particularly in response to competition with the US. While the US, especially under President Trump, pursued anti-globalist and anti-multilateral strategies, China has embraced multilateralism. It has sought to build alliances, forge new trade partnerships, and create collaborative economic opportunities worldwide.

China is also trying to create new paradigms for cooperation among developing countries. Historically, institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and other multilateral organizations have been dominated by advanced economies and have not fully addressed the needs of developing nations. The global rules have largely been written by a small group of wealthy countries, even though much of today’s population, GDP growth, and economic dynamism comes from what was once considered the “periphery.”

China is more sensitive to the needs of developing countries and recognizes the injustices in the current international system. It aims to play a more relevant role in addressing these issues.

Of course, China’s efforts are not perfect, and there is a learning curve in pursuing strategies that genuinely result in mutual benefits. But I believe that China’s approach still leans toward creating win-win solutions rather than embracing a zero-sum mindset.

Editor: huyueyue

Anonymous

Prof Jin is a learned economist showing her understanding and knowledge of China’s economic policies within the global context. She explains clearly and convincingly in a fair manner. She is a voice of authority and expertise. I am glad that I have the opportunity to listen or to read this interview.

Anonymous

a totally different landscape of China’s and world’s economy.