Chinese Immigrants Are Queuing to Return Home

【This article is excerpted from the Chinese financial blog “表外表里”, authored by Chen Zijie and Cao Binling】

Taking one last look at the 700-square-meter courtyard and bidding farewell to her “home” in New Zealand, Liu Lu picked up her luggage and, along with her husband and child, embarked on the journey back to China.

After spending 10 years abroad, she transformed from a naive international student into a stable “Kiwi” with a house, a car, and an enviable comfortable life. Yet, she still chose to leave.

Shuige, who moved to Canada nearly 20 years ago, embarked on the journey back even earlier than Liu Lu. He invested over 200,000 yuan in the process: flights were constantly rescheduled, and his family of four ended up buying eight tickets, taking whatever flight they could; the school hastily arranged for his child wasn’t ideal, costing him an additional 140,000 yuan in “tuition” for a better option…

But Shuige believes it was all worth it. “Returning to Hong Kong feels like a rebirth,” he says.

There are many others like Liu Lu and Shuige who are making the return journey: Chen Le in Germany found that half of her compatriots around her also wanted to return to the embrace of their homeland, and Mary, whose career is flourishing in the UK, chose to return to live a grounded life.

An increasing number of people, once eager to embrace a different life and fulfill immigration dreams by moving to foreign lands, are now queuing up to return home.

On social media platforms, topics related to popular immigrant countries are filled with voices of disillusionment. The trending topics of “return migration” and “anti-gloss” continue to rise in popularity, with shares exceeding tens of thousands.

When dreams meet reality, those in search of a better and more comfortable living environment find themselves circling back to their roots.

Do Chinese people only love the “freedom lifestyle” through rose-colored lenses?

Serene ancient streets, floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking a harbor at night, rackets slick with sweat… The “happy fragments” Chen Le chose could combine to create an illustrative guide of the relaxed European lifestyle.

Upon hitting the send button, the familiar red numbers began to jump, with friends and family from home quickly liking her post. The comment section soon filled with envious remarks like “Your everyday life is my poetry and faraway land,” and “I envy your freedom.”

However, Chen Le had her struggles – these seemingly pleasant and leisure activities were merely her efforts to combat depression.

Nearly a decade in Germany, and she still couldn’t get used to the overcast, sunless weeks of the long winters. By three or four in the afternoon, when dusk descended, walking beneath the low clouds brought a feeling akin to being exiled to a desolate place.

To fight off the “winter blues”, she had to pack her 30-day annual leave with plans, just to find a sunny beach to lift her spirits. Her home was stocked with “artificial sunshine” and plush toys to create a cozy atmosphere.

“In China, exercise and travel are often icing on the cake, but in Germany, they’re necessary for maintaining normal mental health,” she lamented. In contrast, Wang Youkai, living in New Zealand, had a better environment.

Upon arriving in picturesque New Zealand, he was captivated by the endless coastlines and vast pastures. Parks and lakes were everywhere, making him marvel, “Every frame is beautiful enough to be a wallpaper.”

Yet, no matter how beautiful, the scenery eventually became familiar, and after the initial awe, the loneliness of the sparsely populated land began to surface. Especially as a socially inclined Beijing native, not finding people to chat with gnawed at him.

“Everyone lives far apart; unlike in China, you can’t frequently gather or visit,” Wang Youkai explained. Moreover, abroad, there’s a strong sense of boundaries between people, and meeting requires scheduling days in advance, lacking the spontaneity of a “let’s go now” moment.

Seasoned Canadian immigrant Shuige also discovered that the shattered lens of Western lifestyle may not suit the constitution of Chinese people.

He vividly remembers experiencing severe chest pain while jumping rope to exercise after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, feeling weak and collapsing to the floor.

He managed to call his family doctor, who, while expressing “genuine concern” for his condition and stating “I understand your needs,” ultimately resolved to: “If it’s urgent, we can refer you to a specialist.”

Referred to the specialist, the cycle of redundant phrases repeated, and when asking for an appointment, Shuige was stunned—the earliest appointment was three months away.

“If I had a heart condition then, the consequences would’ve been dire,” Shuige recalling with lingering fear, couldn’t accept the laissez-faire doctors, despite Canada’s free public healthcare.

Sasa, who battled the aftereffects of COVID-19 alone in Germany, nearly succumbed to this healthcare system.

During that period, she suffered from two months of insomnia, total loss of sight and taste, and would sweat profusely with any exertion. When she asked doctors why she couldn’t sleep, the response was “Many people experience insomnia”; when complaining about eye discomfort, the advice was simply “Blink more.”…

Even after laying out her ECG and test results on the table, the doctor gave a quick glance before indicating “All indicators are normal, don’t waste your time here,” prompting her to book a flight back to China immediately.

Upon her return, Chinese doctors, after merely listening to her symptoms, accurately pinpointed the problem. After a few doses of traditional Chinese medicine, her insomnia vanished and her body was back to normal after two more treatment courses.

“I used to feel that Chinese hospitals were cramped, and consultations were too brief to be thorough.” Now Sasa realizes that due to China’s large population, doctors have encountered more cases and are more seasoned when it matters.

After this major illness, she reevaluated her overseas experiences, realizing that aside from different life backgrounds, she never truly integrated into the foreign job market either.

Facing Cultural Barriers in Overseas Careers and Missing out on China’s Rapid Development

“Time is running out, and if you don’t hurry, you’ll lose the game,” her colleague counted down, yet Sasa was fixated on the word “Nativity” on the quiz board, struggling to grasp its meaning.

It was part of a team-building game requiring participants to work in teams to complete challenges with Asian colleagues. Despite being near-native in English, she didn’t anticipate getting stuck on the first challenge.

The puzzle solution revealed “Nativity” specifically referred to “the birth of Jesus Christ,” and her teammates nodded in understanding while Sasa applauded with an uneasy smile: “They knew we weren’t religious, but tested us on religious topics anyway.”

Encountering cultural barriers like these wasn’t new. No matter how familiar she was with locals, her inability to share a knowing smile when European celebrities or local jokes were mentioned repeatedly highlighted her “foreigner” status.

“Many things foreigners consider general knowledge simply aren’t stored in our brains,” Sasa sighed. In a non-native language environment, she had to expend cognitive effort to comprehend conversations, making her feel “dumber” and hindering her ability to vie for promotions.

Similarly, Chen Le felt out of place in overseas workplaces too. She recalls her excitement discussing AI technology with German colleagues after DeepSeek’s buzz, only to be doused with skepticism—“Can this ensure our data security?”

Not only DeepSeek, her company, to ensure data security, prohibited tools like Google and ChatGPT on work computers, while her Chinese friends comfortably trained AI, she was left dealing with outdated local software.

“In the Western mindset, if something is properly done, better not change it,” Chen Le noted. As she started digital marketing, she had ambitious ideas but was often constrained by concerns over data risks or client relationship management.

Half a year passed, filled with repetitive work like bi-weekly web updates and quarterly emails, leaving her creativity stunted. Observing her domestic peers’ innovative business models, she felt deeply frustrated, asserting “Western societies seem more primitive, while the East appears more modern.”

Previously, she persevered due to Germany’s work-life balance, free from a mid-life crisis and secure in long-term employment.

But now, winds of change are sweeping across Europe, especially in Germany, where the automotive industry’s lag in electrification has led major companies like Volkswagen to implement sweeping “cost-reduction plans”.

“Job layoffs in Europe aren’t as scary as they might seem. You can enjoy generous compensation and take a break for a year or two, but what comes after?” says Chen Le. It’s the decline of industries that’s truly unsettling.

Working on botany research with her husband in New Zealand, Liu Lu finds it hard to believe the lab’s setup reflects that of a developed country: the office walls are peeling, the equipment is outdated, reminiscent of China in the ’80s and ’90s, and the precision of the data they generate isn’t even suitable for publication in a paper.

Even more scarce than the hardware is their project funding: a single project can be as low as tens of thousands of RMB, with hefty management fees and experimental labor costs, leaving a pitiful amount of money for actual research.

Moreover, once Liu Lu’s husband completes his last ongoing project, their funds will be completely drained as resources shift towards climate change topics.

After a visit to China for an exchange, her husband has been nostalgic about China—where even at ordinary undergraduate university laboratory centers, all kinds of basic instruments are readily available, and even cutting-edge equipment isn’t uncommon; not to mention the funding, where a single project might cost millions, and the reagent prices are just a quarter of those in New Zealand.

The stark contrast left them thrilled when receiving offers from Chinese universities. “But to be honest, we were very hesitant at first,” Liu Lu admits, given the intense competition in China that can be daunting.

The once-promised land has become a “fortress” to escape from.

“Don’t you Chinese ever rest? Why are you still sending work messages in the group chat over the weekend?” asked her husband, eyes filled with curiosity. Resigned, Liu Lu began yet another round of “education.”

This isn’t the first time Liu Lu has bridged the “cognitive gap” for her husband. Since they both took positions in a Chinese university, she feels like she has become a “kindergarten teacher.”

Her New Zealand native husband struggles with the language and institutional differences in China: applying for a project requires filling out various forms and approvals; during group meetings with students, they seem to speak past each other. Liu Lu finds herself juggling the roles of translator and assistant to help him adapt quickly.

Besides comforting her husband, she also has to find time to “console” herself. In New Zealand, she used to live in a 400-square-meter standalone villa, but now, their family can only squeeze into a “concrete box.” The contrast is significant.

Nonetheless, despite various discomforts, Liu Lu does not regret coming back. “There’s no perfect situation in the world; just take the best option available right now.”

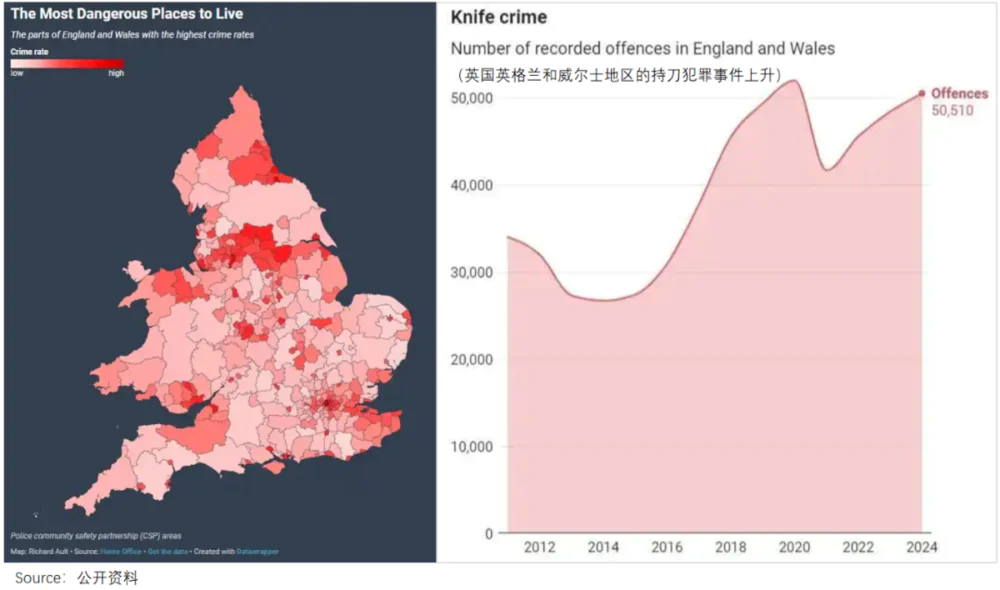

To Mary, who faced even greater shocks, these grievances pale in comparison to matters of life and property safety. When she went to study in the UK in 2009, she never imagined that London, once an “promised land,” would become a “lawless zone” a decade later.

“Yesterday, while shopping in Westminster, my bag was stolen,” “My colleague was held up at knifepoint while buying a bottle of wine…” She first noticed the decline in public safety from stories shared in social groups.

Soon after, she experienced it first-hand: during a business trip, she witnessed a gunfight outside her hotel window; losing items became a routine, and the most extreme case was losing two phones within six months.

Mary had foreseen such chaos, given the worsening political and economic issues in recent years, compounded by cultural conflicts and integration challenges from the influx of immigrants and refugees.

Understanding, however, does not equate to acceptance. The constant anxiety is too exhausting. Mary, fed up, wanted to leave the UK for another Western country, only to find through consultations that the idyllic overseas world described in magazines is collectively collapsing.

Shuige, having acquired Canadian citizenship years ago but now striving to regain his Chinese citizenship, resonates deeply with the situation. He invested a fortune in his startup and diligently endured the required residency years to acquire his Canadian citizenship, only to see others easily attain it via refugee status.

Moreover, once they arrive, the government provides housing and various subsidies—even without a job, they can receive five to six thousand in assistance monthly; if they have children, they receive additional maternity and child benefits.

“For instance,” Shuige grumbles, “Indians arrive with their families and focus on having children, three or five kids is common, so without working, they can earn 20,000 a month.”

The burden falls on taxpayers, naturally. Canada’s income tax can reach a staggering 46%, meaning half of a worker’s salary might go to taxes; additionally, buying an item requires paying a 13% sales tax.

Not only is income heavily taxed, but property rights are also precarious. Local laws dictate that landlords can’t evict tenants who can’t pay rent, leading to widespread “rent bullying”—tenants can find arbitrary excuses to avoid paying rent and continue living for free.

“A friend of mine faced this situation, with tenants occupying the house without returning it, and only after six months of litigation was he able to reclaim it at a significant financial loss.” Shuige always finds the situation absurd.

Working hard and diligently accumulating assets, only to end up being a “bridal dowry,” has pushed Shuige to the edge. The sudden legalization of marijuana has made “escaping” even more urgent.

Attending a party carelessly might result in consuming food laced with marijuana; at home, the smell of secondhand marijuana smoke from neighboring apartments is noticeable; among students, marijuana use has become the “new social norm”… Living in such an environment, Shuige worries not only about his own exposure but also fears for his children’s future.

Therefore, learning about the possibility of “returning to China” through Hong Kong’s Quality Migrant Admission Scheme, he swiftly relocated his family to Hong Kong, planning to wait seven years before reclaiming Chinese citizenship.

(Liu Lu, Shuige, Chen Le, Mary, and Sasha are pseudonyms. Special thanks to bloggers Yonghe Chen, Little Friend and Nature, Meng Dele, Sasa.DE, and Uncle Beijing with Eye Bags for their support of this article.)

Editor: Zhongxiaowen