China’s Ukraine Peace Plan: A Solution from Day One

On the eve of the Ukraine war entering its fourth year, West’s policy has swung from Biden’s “as long as it takes” to Trump’s “end-it-now-or-else” mode. It remains uncertain how quickly the Trumpian art of the deal could silence the guns across the 2,400-kilometer line of skirmishes.

Regardless, China’s “principled neutrality” has played a crucial role in preventing the conflict from spilling beyond Europe and even spiraling into a nuclear confrontation towards World War III.

Beyond China’s vast economic power and military potential, the key to this stabilizing influence lies in its “principled” and “impartial” neutrality. Unlike the “pure,” “permanent,” or passive neutrality seen in European history (e.g., Switzerland), China does have its opinion and preference regarding the nature of the Ukraine war, particularly its origin, which is NATO expansion.

The East: NATO’s Fatal Attraction

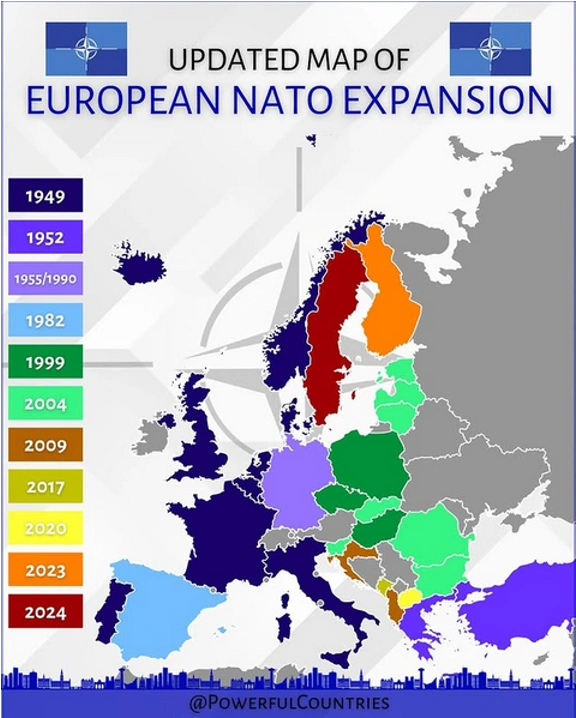

From the beginning, Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine has been framed in the Anglosphere as an “unprovoked attack.” From China’s perspective, however, Russia’s use of force was the inevitable consequence of NATO’s relentless eastward expansion. Since the end of the Cold War, there have been five waves of such expansions to the east despite strong warnings from Moscow.

China is not alone in this assessment. In 1997, George Kennan, the chief architect of America’s Cold War containment strategy, warned that NATO expansion “would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.” Former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jack Matlock echoed Kennan’s concerns, calling the expansion a “misguided” decision that “may well go down in history as the most profound strategic blunder….” Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Defense William Perry went as far as to resign because he disagreed with Clinton’s “rosier scenario” about NATO expansion. Henry Kissinger, too, cautioned that Ukraine’s survival and thriving must be based on its neutrality as a “bridge,” not a battlefield, between Russia and the West.

Despite these sober warnings from some of the West’s most seasoned strategists, their insights were largely dismissed by the liberal interventionists and neoconservatives who shaped post-Cold War foreign policy. The world now is living with the blowback of the West’s arrogance and ignorance.

China’s “Constructive” Neutrality: Pragmatism, Humanitarianism, and Political Realism

Maintaining a neutral and impartial stance on the Ukraine war in a deeply divided world is no easy task. Yet China chose the hard way. Its position rests on several core principles: upholding the UN’s commitment to sovereignty and territorial integrity, supporting all efforts toward a peaceful resolution of the crisis, and advocating for common, comprehensive, and sustainable security for all, not just a few. China has also consistently emphasized the need to protect civilian lives and property, reframed from providing weapons to the warring parties, and urged restraint to prevent further escalation.

China’s neutrality in the Ukraine conflict, therefore, is not passive or indifferent but rather a blend of pragmatism, humanitarianism, and political realism. Unlike the European tradition of neutrality as an end in itself or neutrality for neutrality’s sake, China’s approach is one of “constructive engagement,” as described by Zhao Huasheng, a prominent Russologist at Fudan University in Shanghai. Reflecting this commitment, China’s special envoy for Eurasian affairs, Li Hui, conducted four rounds of shuttle diplomacy between May 2023 and July 2024 (May 2023; March, May, and July 2004), seeking a political resolution to the ongoing conflict.

Normal Relationship in Abnormal Times

China’s principled neutrality in the Ukraine war is grounded in its “normal ties”—or balanced and stable relations—with both Ukraine and Russia. At a minimum, both Russia and Ukraine are China’s friends. It is immoral, or amoral, for China to support one at the expense of the other.

For years, Ukraine has been a vital economic partner for China. Until 2022, Ukraine served as the most significant hub for China’s expansive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Central and Eastern Europe. Beyond this, Ukraine also played a critical role in China’s military modernization in the post-Cold War era.

At the height of the 2013 Crimea crisis, China extended an unprecedented $8-billion economic package to Ukraine—the largest offer from outside Europe. An indicator of this normal, and strong partnership with China is Ukraine’s continuous hold on its one-China policy, despite increasing Western support for Taiwan’s independence. During his visit to China in May 2024, Ukraine’s then-FM Kuleba went as far as to say, “China is a great country, and Ukraine and China are not only strategic partners but also important economic and trade partners.”

In the case of China-Russia relations, the West often portrays China as Russia’s “chief enabler” in the Ukraine war. But such a characterization distorts the nature of the China-Russia relationship.

The current Sino-Russian “comprehensive strategic partnership” is essentially a normal relationship after the 10-year Sino-Soviet alliance between 1949 and 1959 and 30-year adversarial relations from 1960 to 1989. A key element of this normal relationship is the absence of ideology, which exaggerated, unnecessarily, the “love-hate” oscillation between 1949 and 1989. Now the two sides treat each other as who they are rather than what they wish to see each other.

In the strategic domain, the China-Russian partnership is not an alliance because it does not have an interlocking mechanism similar to NATO’s “Article 5” that automatically commits one side to the other in times of war. Instead, this normalcy provides two large powers with freedom of action and strategic depth after the “best” and “worst” times in the past.

While China and Russia’s relationship is not without challenges, their differences are usually managed through dialogue and compromise, rather than being politicized. Largely because of this, the current partnership relationship is perhaps the most equal, most stable, and least harmful form of interaction between the two powers. This is very different from much of the 19th and 20th centuries when Russia forcefully inserted itself into a weak and chaotic China by either Czarist imperialism or by Bolshevik’s revolutionary idealism and Stalin’s brutal realism.

Tales of Russia’s Two Borders

A cornerstone of such a normal and stable relationship between Moscow and Beijing is the final resolution of the centuries-long border issue—a stark contrast to Russia’s unsettling and conflict-ridden western borders.

Both Gorbachev and Yeltsin began their presidencies with sweeping pro-Western policies. The initial enthusiasm of Gorbamania and Yeltsin’s “shock therapy,” however, quickly soured into a state of “cold peace.” This deterioration was largely driven by NATO’s relentless eastward expansion, despite earlier Western assurances of “not one inch” moving eastward. As a result, Russia’s “not-so-quiet” western front has remained volatile, ultimately culminating in the largest and most intense conventional war in Europe since World War II with the potential of escalating into World War III, or even nuclear conflict.

In contrast to its romantic and often tragic interactions with the West in the post-Soviet decades, Russia’s relationship with its eastern neighbor, China, has been far more pragmatic and uneventful. It took 22 years (1982–2004) for both sides to fully normalize relations and reach a settlement on the border issues. A major step in this process was the formation of the Shanghai-Five (China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan) in 1996, which institutionalized demilitarization, confidence-building measures, border demarcation, and long-term stability. The once most heavily militarized frontiers of the Cold War are now a zone of stability and thriving cross-border trade, cultural exchange, and social interaction.

The current strategic partnership relations between China and Russia, therefore, have strong internal dynamics, and institutionalized channels of communication and management. Both sides benefited enormously from this normalcy in bilateral interactions.

Had the West pursued a similar pragmatic approach with Russia regarding border disputes, as China did, the devastating loss of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian and Russian lives might have been averted.

“The Ukrainian conflict should never have happened, and would not have happened if I were President… But as I have made very clear for quite some time, this could now end up being World War III,” declared presidential candidate Donald Trump back in September 2022. In the 28 months leading up to his second presidency (Jan. 20, 2025), tens of thousands more Ukrainians and Russians perished in the largest conventional war in Europe since World War II.

While US President Donald Trump is rushing to undo his predecessor’s war, China remains steadfast in its posture of principled neutrality not just for ending the bloody war but is poised to shape the postwar settlement into a more just and durable peace in Europe and beyond.

Editor: huyueyue