Sweden Says Only 50% Chance to Save My Womb—China Promises 99%

At 58, Swedish doctor Anna Hammarström and her 75-year-old husband, Eskil Hammarström, are already parents to 11 children. Among their brood are Klara Hammarström, a celebrated Swedish pop singer; Ingemar Hammarström, a national junior champion in equestrian show jumping; and Ellen Hammarström, a TV host for equestrian programs. Their family’s extraordinary life even inspired a reality show, The Hammarström Family, produced by Sweden’s national television network.

Anna Hammarström and her families

Anna Hammarström and her families

This year, Anna was pregnant with their 12th child. This pregnancy came from a frozen embryo that the couple preserved years ago. Originally stored in Ukraine, the embryo had to be rescued and relocated to Georgia due to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War before being implanted into Anna’s uterus.

Anna loves the feeling of being pregnant. Despite her age, the hormonal changes bring her energy and vitality. To mitigate the risks associated with her advanced maternal age, she follows a strict diet and takes daily walks with her dog, Bella.

The baby’s movements were strengthening as it grows. However, a routine ultrasound revealed that Anna’s placenta might be improperly positioned. Then, she is transferred to Lund University Hospital for further evaluation.

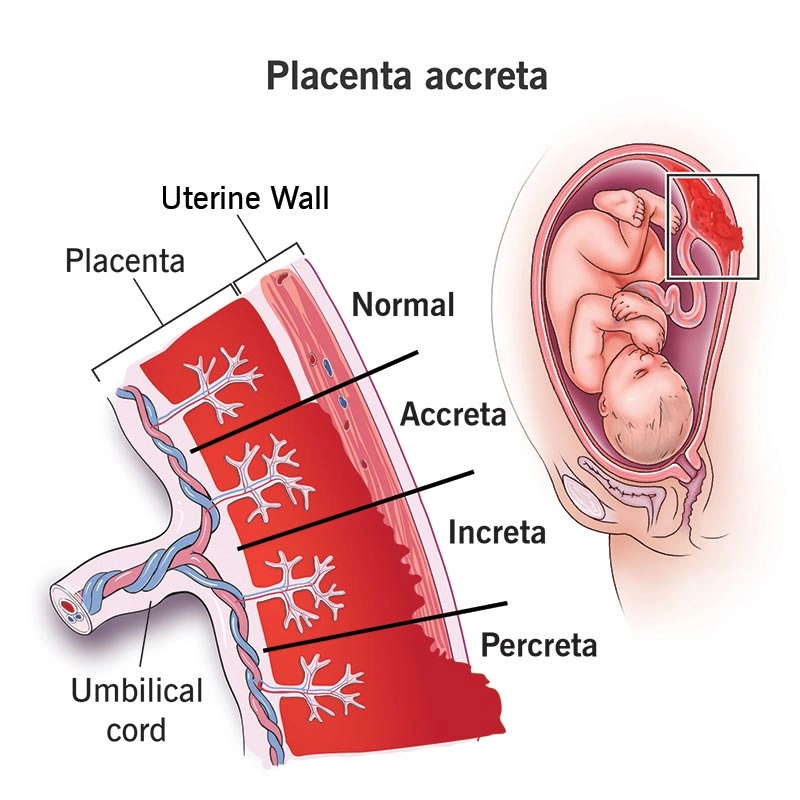

At Lund, specialists diagnosed Anna with a severe pregnancy complication: invasive placenta, or placenta accreta, a condition where the placenta grows into the uterine wall. This could lead to life-threatening hemorrhaging during delivery.

The condition is more commonly seen in women who have undergone previous C-sections. The placental villi can grow along uterine scars and invade the uterine muscle layer. Anna, who has triplets in her first pregnancy and twins in her second, has undergone three C-sections, significantly increasing her risk of developing this condition compared to the average pregnant woman. In Sweden, approximately 50 cases of invasive placenta are reported annually.

The Swedish specialists proposed a treatment plan to deliver Anna’s baby several weeks before the due date via C-section, combined with a hysterectomy. This approach is designed to prevent severe hemorrhaging during the detachment of the placenta and is considered the “gold standard” for managing invasive placenta in Europe and the United States.

However, Anna refused to accept this surgical plan. Despite being 58 and having implanted her last frozen embryo, she was determined to keep her womb. As a doctor, she understood that removing the uterus is a major operation with potential risks and long-term complications. “For me, it’s about how I perceive myself as a woman,” she explained. “Why should I remove a healthy organ? The same applies to any part of my body.” Doctors at Lund University Hospital warned that if she insisted on keeping her uterus, there was at most a 50% chance of preserving it—a probability Anna found unacceptably low.

Thanks to her profession, Anna was skilled at researching medical information online. After several days of relentless searching, she discovered a solution that promised a safe delivery while preserving her womb: traveling to China for a C-section.

Invasive placenta typically occurs in women who have undergone previous C-sections.

China is known for its historically high C-section rates but saw relatively few cases of women with prior C-sections having additional pregnancies due to the strict one-child policy. However, since the introduction of the two-child and three-child policies, this situation has changed significantly. Data suggests that the incidence of placenta accreta among Chinese women is 1 in 250, compared to the global average of 1 in 5,000—19 times higher. This has given Chinese doctors extensive experience in managing invasive placenta cases.

Without hesitation, Anna sent an email to Dr. Wang Hongmei at Shandong Provincial Hospital in northern China. In the email, she explained her situation and mentioned that she had come across Dr. Wang’s published research on surgical techniques for invasive placenta. Anna expressed her desire to travel to Shandong for a C-section under Dr. Wang’s care.

Dr. Wang replied within hours, confirming that Anna could undergo surgery there but cautioning against the long journey from Sweden, citing safety concerns.

However, this response did not deter Anna. Once she learned that surgery was possible, she immediately began applying for a visa and booking flights. At 35 weeks pregnant, she successfully flew to Jinan, Shandong Province, with her husband. When Dr. Wang Hongmei heard that her Swedish patient had visited museums and shopped for gifts for her children after arriving, she promptly called Anna to the hospital to arrange for her admission.

Anna was impressed by the efficiency of blood collection in China’s public hospitals. “Patients line up at the nurse’s station, and when it’s your turn, you just stick your arm out” she remarked.

After a series of tests, Dr. Wang assured her that she had a 99% chance of preserving her uterus, a significantly higher estimate than the 50% given by specialists at Lund University Hospital. Dr. Wang explained that between 2016 and 2018, during the early years of China’s two-child policy, she performed 2–3 invasive placenta surgeries every week, which made her confident in this surgery.

Dr.Wang and Anna

Dr.Wang and Anna

The C-section was performed under spinal anesthesia, allowing Anna to remain fully conscious throughout the procedure. The surgery lasted about an hour, with surgeons entering through an old C-section scar. The total blood loss was comparable to that of a standard C-section. After the surgery, Dr. Wang explained in simple English that although Anna’s placenta covered a large area, it had not deeply invaded the uterine wall.

Anna and her husband named their 12th child Rosa. Due to being born prematurely, Rosa was placed in the neonatal intensive care unit for a few days. After being discharged, the family stayed in China for another month, then returned to Sweden, carrying a variety of gifts from Dr. Wang.

Once back in Sweden, Anna set a new goal: to invite Dr. Wang to Sweden, so she could share her surgical techniques with Swedish doctors.

A reporter asked Anna, “How do you view the risks of being pregnant at your age?”

Anna replied, “I’m not someone who particularly enjoys taking risks. I don’t go skydiving, I don’t speed while driving, and I don’t do extreme skiing. I’ve assessed my physical condition and believe I can handle the pregnancy. All the risks can be managed with proper monitoring.”

The reporter then asked, “But wasn’t traveling to China in the later stages of your pregnancy a risk?”

Anna responded, “I wasn’t worried. I have confidence in the medical care I could receive in China. Swedish doctors aren’t as experienced with dealing with this kind of complication.”

In fact, Anna is not the first Swede to travel a long way to China for medical care. Pernilla, a 33-year-old Swedish woman, suffers from spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). In 2017, a drug called Spinraza, which can effectively treat SMA, was approved for use. However, Swedish authorities determined that the cost-effectiveness of providing the drug to adults was too low. As a result, Sweden only offers the treatment to SMA patients under 18. At the time, there were 72 SMA patients across Sweden who did not have access to the new drug, and Pernilla was among them. Eventually, Pernilla discovered that the drug was priced at just one-seventh of its cost in Sweden on the Chinese market. As a result, she now travels to China every quarter to obtain the medication.

Alma, a 2-year-old Swedish girl, was diagnosed in May of this year with a fatal metabolic disorder called MLD. The cost of a single dose of the medication to treat MLD in Sweden is over $2 million, and Swedish hospitals refused to administer the drug to Alma. Subsequently, Alma’s parents discovered that Chinese doctors were able to treat this condition, with treatment costs being ten times lower than in Sweden.

In Sweden, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, people are traveling to the other side of the globe to seek medical treatment. Meanwhile, China has not turned these international patients away, offering them the same affordable and efficient care as it provides to its own citizens.

Editor: Li Jingyi

Anonymous

I wonder if someone from the western media will mention it,

They always write slander about the Chinese

Anonymous

Thank you China for your effort in promoting life science and humanity

Anonymous

How can the rest of us afford to fly to the Chinese mainland for medical treatment?

Anonymous

how much do they charge for treatment tho in china for foreigners?