To Uncover the Secret, the Japanese Tear Down Chinese EVs

On November 18, Chinese automaker BYD became the first company globally to produce 10 million EVs. In September alone, the company sold nearly 420,000 cars—equal to its total sales for all of 2020. This rapid rise of Chinese EVs has not gone unnoticed in Japan, where automakers have long been on edge. To uncover the secret behind this success, Japan’s industrial sector adopted a straightforward approach several years ago: tearing down Chinese cars.

A Japanese attendee was seen lying on the ground photographing the car’s chassis at an expo held in Tokyo.

A Japanese attendee was seen lying on the ground photographing the car’s chassis at an expo held in Tokyo.

Learning Through Disassembly

In 2021, NHK, Japan’s renowned public broadcaster, aired a program showcasing the disassembly of a Chinese Wuling Hongguang MINI EV. By the end of the show, the host and a correspondent looked visibly concerned, admitting, “If this enters the Japanese market, it would pose a serious threat to domestic brands”

In the NHK program, a Wuling Hongguang MINI EV was sent to Nagoya University for disassembly.

In the NHK program, a Wuling Hongguang MINI EV was sent to Nagoya University for disassembly.

Recently, Japanese trading firm Sanyo Trading purchased 16 Chinese EV models, including BYD’s ATTO 3 and NIO’s ET5, for disassembly. They plan to expand this effort by disassembling more models from brands like Li Auto, AITO, and even Xiaomi to uncover the reasons behind the success of Chinese EVs.

Disassembled BYD’s Atto 3 EV on display

Disassembled BYD’s Atto 3 EV on display

Nikkei BP, Japan’s largest publisher, has also joined the disassembly frenzy. They published a 350-page book documenting the entire process of disassembling BYD’s Seal, complete with a DVD featuring teardown footage. Priced at $5,700, a package with additional services costs up to $8,600. In September, Nikkei BP bought a Zeekr 007 from China for similar scrutiny.

Toyota, one of Japan’s “Big Three” automakers, has reportedly torn apart several BYD models, including the Han EV, Tang DM, Dolphin, and Yuan PLUS, for detailed study.

But what exactly have the Japanese uncovered?

Low Cost, High Performance

First, Japanese analysts concluded that “Chinese automakers excel at low-cost production,” thanks to two key factors:

Highly Integrated Components: Chinese EVs integrate multiple key components into single units. For instance, their “E-Axle” system combines eight critical parts—including the motor, inverter, reducer, onboard charger, and DC-DC converter—reducing production costs, vehicle weight, and failure rates while simplifying maintenance.

E-Axle electric drive system integrates eight components into a single unit.

E-Axle electric drive system integrates eight components into a single unit.

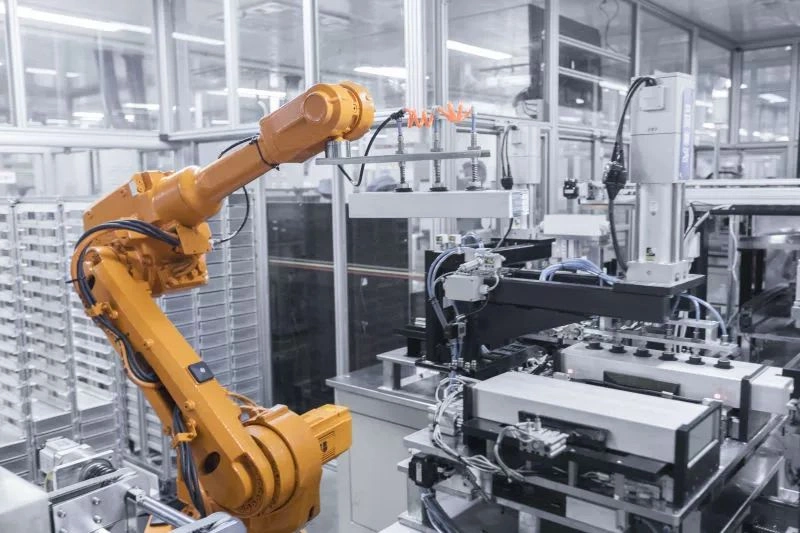

Localized Supply Chains and Shared Components: Many Chinese automakers source components domestically or produce them in-house, allowing for greater parts standardization across models. BYD, for instance, slashes costs by producing components in-house and sharing them across its lineup.

BYD Battery Production Line

BYD Battery Production Line

NHK’s teardown of the Wuling Hongguang MINI EV revealed that its key electrical components—such as batteries, semiconductors, and capacitors—were entirely sourced from Chinese suppliers, with no parts from Japanese firms.

Masayoshi Yamamoto, a former professor at Nagoya University who participated in the teardown, remarked that the MINI EV’s cost control and precise design target were unmatched. “With Japan’s current supply chain, it’s impossible to produce an EV of the same quality and price,” he admitted.

Second, Chinese automakers excel in software and algorithm development. Nikkei BP’s teardown of the Zeekr 007 highlighted its cutting-edge integrated die-casting technology and 800V high-voltage drivetrain. The vehicle’s high-performance ECU (Electronic Control Unit) features NVIDIA’s in-car SoC (System on Chip), supporting advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) with sensors like LiDAR.

While Japanese automakers excel in precision manufacturing, their struggles in software and algorithms underscore their lag in EV technology.

The Unreplicable Chinese Model

After tearing down the cars, Japanese automakers realized that even if they reassembled an identical vehicle using the same components, they might not match China’s cost or performance. This situation is reminiscent of DJI, the Chinese drone giant. While many of DJI’s components are sourced from the global supply chain, the U.S. has failed five times to sanction the company effectively. The reason? Products with comparable configurations in the U.S. market are typically 3-4 times more expensive and fall short in performance.

DJI MAVIC 3

DJI MAVIC 3

Banning DJI would drastically increase the cost of drone procurement, creating challenges for various public service sectors and industries in the U.S. Similarly, the core competitive advantage of Chinese EVs and DJI drones lies in their ability to deliver low cost and high performance.

Japanese Automakers’ Ongoing Anxiety

Despite the competition, Japanese automakers retain certain advantages. As the world’s third-largest auto producer, Japanese cars are celebrated for their fuel efficiency, durability, and high resale value. Some engines from brands like Toyota and Honda have operated flawlessly for decades. Japan also dominates the global power semiconductor market, with five of the top ten players hailing from the country. Companies like Mitsubishi Electric, Fuji Electric, Toshiba, Renesas, and ROHM collectively hold over 20% of the global market share. ROHM alone controls more than 10% of the silicon carbide (SiC) power semiconductor market and 15-20% of the SiC wafer market.

While the global automobile market is still dominated by gas-power from brands like Toyota, Volkswagen, and Honda, Japan’s frantic effort to dissect Chinese EVs signals the mounting pressure Chinese automakers are placing on their Japanese counterparts. According to data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, Japanese cars held a 23.1% market share in China in 2020. By the first four months of 2024, that figure had plummeted to just 12.2%. In contrast, the market share of Chinese brands surged from 38.4% to 60.7% over the same period.

Clearly, relying on teardown strategies alone won’t solve the challenges Japanese automakers face. In the end, they may be left grappling with the anxiety of being fully outpaced by their Chinese competitors.

Masayoshi Yamamoto and his team at Nagoya University has begun disassembling Xiaomi’s SU7

Masayoshi Yamamoto and his team at Nagoya University has begun disassembling Xiaomi’s SU7