Socialism, capitalism, or Chinism?

Last week, an intellectually stimulating conversation on China’s economy took place among three leading scholars: Radhika Desai, the director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba; Michael Hudson, professor of Economics at the University of Missouri; and Mick Dunford, emeritus Professor at the University of Sussex. We don’t just view it as an interesting exchange of ideas but also as a significant indicator of the future of socialism. Hence, we present to you in the following paragraphs part one of the highlights of their conversation.

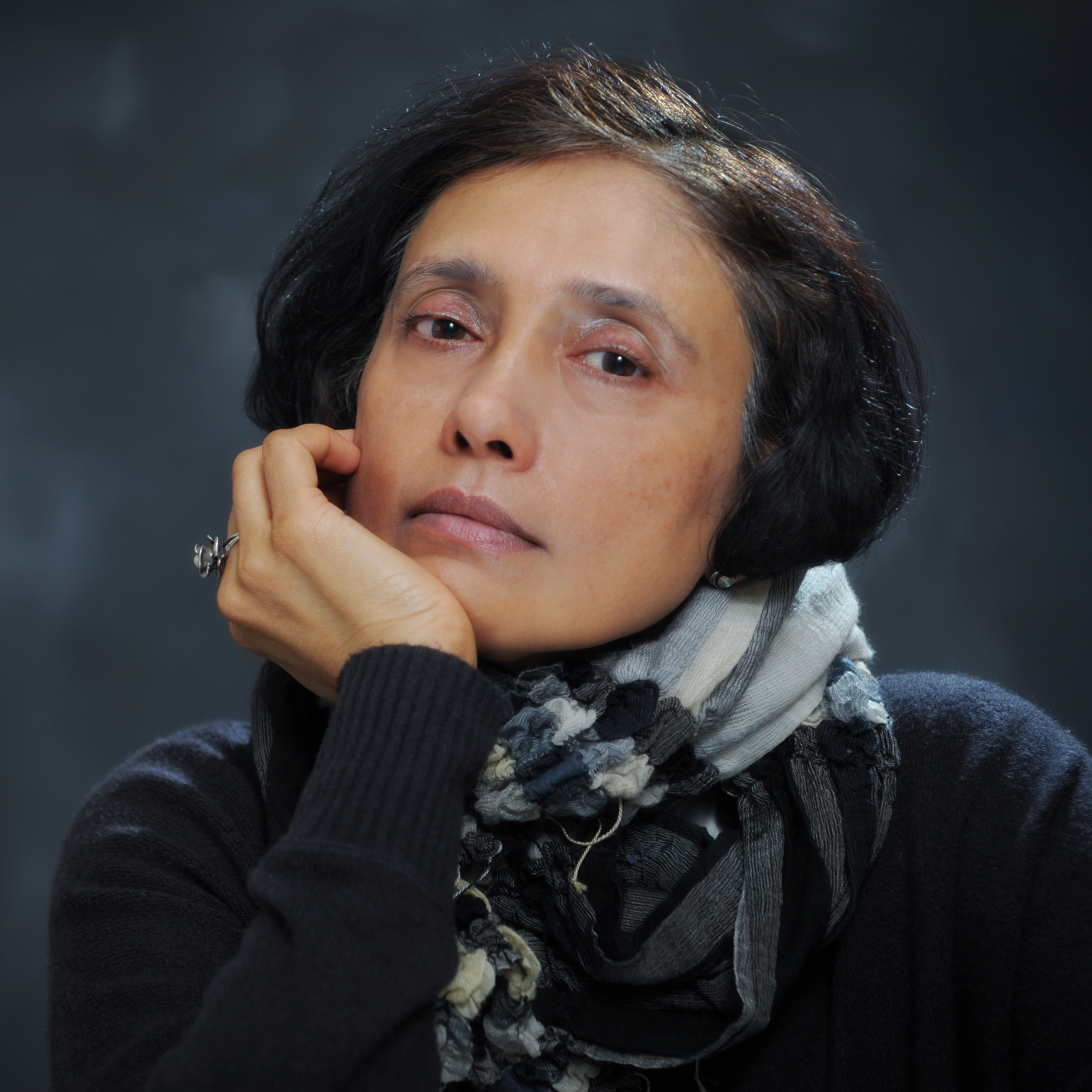

Radhika Desai:

China’s economy is what we are going to talk about today. Where is it after decades of breakneck growth, after the greatest industrial revolution of all time? Where is it going? Trying to understand this is not easy. The disinformation that is fake news, and even what I often call fake science, that distorts the view that any honest person would try to take on China’s economy is simply overwhelming.

If we are to believe the Western press and the leading Western scholars, who are the main generators of Western discourse on China, we are at Peak China. That is, they claim that China has reached the highest point. That is, it can ever be. And from here it’s all downhill, more or less fast. They say that China has inflated a huge real estate bubble in recent years to compensate for the West’s inability to keep up with imports. And that bubble is about to burst. When it does, it will expose China to a Japan-style long-term deflation, or secular stagnation, of the 1980s and 1990s. They have even invented a word to talk about this Japanification. We are told that the japanification of the Chinese economy is imminent, they say that the USA’s trade and technology wars are hitting China where it hurts the most in its exports and its dependence on foreign investment.

We want to start by talking about how to characterize China’s economy. Is it capitalist? Is it socialist?

Mick Dunford:

The way I would characterize China is as a planned rational state. It has maintained a system of national 5-year planning, and it also produces longer-term plans. But it’s a planned rational state that uses market instruments. And China has a very large state sector. And some people have argued that this state sector is in some ways an impediment to growth. And we’ve seen a resurgence of this idea of “Guo jin min tui,” which is used to refer to the idea that the state sector is advancing and the private sector is retreating. It’s actually a very strange concept because the third word is “min” and “min” refers to people.

So what they are actually saying is that these ideas were invented by neoliberal economists, in 2002, the private sector is equated with the people, which I find absolutely astonishing. But the country has a very important public sector. What I find striking is that you can actually turn it around and say, what do these Western economists seem to think China should do, and they seem to think that China should privatize all the assets into the hands of domestic and foreign capitalists? It should abolish capital controls. It should open the door to foreign finance capital. It should hand over governance to liberal capitalist political parties that are actually controlled by capital. I think one of the most fundamental features of the Chinese system is that it’s actually the state that controls capital rather than capital controlling the state. In fact, in this aspect, the Chinese model, and particularly the rule of the Chinese Communist Party, that has basically transformed China from one of the poorest countries in the world to one of the largest industrial powers.

So in a sense it is a planned rational state in which the CPC has played an absolutely fundamental role. And without it, China would never have achieved the national sovereignty that permitted it to choose a path suited to its conditions and to radically transform the lives and livelihoods of its people.

Michael Hudson:

The question is what is the state? There are two aspects of the state in China. One is public infrastructure. And the purpose of China’s public infrastructure is to lower the cost of doing business, because infrastructure is a monopoly. That’s what really upsets American investors. They wanted to buy the phone system, the transportation system, so they could benefit from charging monopoly rents. Just like under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The most important sector that China is treated as in the public eye is money creation and banks. The Americans hope that American banks will come over and do all the lending in China and benefit from China’s growth and turn it into interest.

And instead the Government is doing that, the Government is deciding what to lend to. There’s a third aspect of what people think of when they say state. That’s a centralized economy, centralized planning, Soviet-style. China is one of the least centralized economies in the world because the central government has let the localities go their own way. That’s part of the hundred flowers blooming. Let’s see how each shell locality will maneuver on a pragmatic ad hoc basis.

The pragmatic ad hoc basis means how the localities, villages and small towns are going to finance their budgets. They financed them by selling real estate. Once you realize that the state sector is so different from what a state sector is in America, centralized planning in the control of Wall Street, for financial purposes, finance, capitalism, hyper-centralized planning, you. You realize that China is the antithesis of what the usual view is.

Radhika Desai:

Absolutely. And I would just like to add a couple of points because it ties in very nicely with what you both said. I mean, the fact of the matter is that this was also true of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European countries when they were ruled by communist parties. We generally refer to them as socialist or communist, but in fact they never claimed to be socialist or communist. They just said they were building socialism, especially in a country that was as poor as China was in 1949. And the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party has always understood that in order to build socialism, there has to be a long period of transition in which a complex series of compromises have to be made in order to steer the economy in the direction of socialism.

So from the beginning, the revolutionary state in China was a multiclass state and a multiparty state. And people very often don’t realize that while the Chinese Communist Party is the overwhelmingly most powerful party in China, there are also other parties that reflect the original multiclass character of China.

Now, it’s true that since 1978 the government has loosened much of its control over the economy, but the important thing here is that the Communist Party retains control of the Chinese state. The way I like to put it this way, there are a lot of capitalists in China. Yes, these capitalists are very powerful. They are running some of the biggest corporations in the world. They are very influential within the Communist Party. But what makes China meaningfully socialist or meaningfully on the road to socialism? Let’s put it this way, is the fact that the reins of power are ultimately in the hands of the leadership of the Communist Party of China, which owes its legitimacy to the people of China rather than to the reins of power, the reins of state power are not held by the capitalists. They are held by the Communist Party leadership.

So in that sense I would say that China is meaningfully socialist, although as Mick pointed out, there is a very fair, quite large private sector in China, but the state sector is also very large. And the extent of state ownership means that even though the private sector is very large, the state retains control over the overall pace and pattern of growth and development in the country.

And I just want to add one last thing here, which will become quite important as we discuss the various other points. And that is that the financial sector in China remains very heavily controlled by the state. China has capital controls. China has a fair amount of financial repression, and China’s financial system is designed to provide money for long-term investment that improves the productive capacity of the economy and the material welfare of the people. And that is completely different from the kind of financial sector that we have today.

Mick Dunford:

The point is that the government sets strategic goals, relate to improving the quality of life for all Chinese people. It has strategic autonomy, which gives China the ability or the possibility to actually choose its own development path.

And I think that’s something that very much distinguishes China from other parts of the global south, which have had much more difficulty, in some ways, in accelerating their growth, partly because of their debt and their subordination to the Washington financial institutions.

So I think this is critically important. The role of sovereignty and autonomy in enabling China to make choices that are appropriate to its circumstances. And at the same time make choices that are driven by a long-term strategic goal of transforming the quality of life for all Chinese people.

Michael Hudson:

I want to say a word about sovereignty. You put your finger on it. That’s really what makes it different. What makes other countries lose their sovereignty is when they allow, how are they going to finance their investment? If they allow foreign banks to come in to finance their investment, if they allow American and European banks to come in, what are they financing, a real estate bubble? A different kind of real estate bubble, they are financing takeover loans, they are financing privatization. Banks don’t lend for new investment. China is making a lot of money to finance new tangible investment. Banks make money, so you can buy a public utility or a railroad and then just load it up with debt. You can borrow and use the money you borrow to pay a special dividend. If you’re a private corporation.

Well, and pretty soon the come the country that follows this dependence on foreign credit ends up losing its sovereignty. The way China has protected its sovereignty is by keeping money in the public domain and creating money for actual, tangible capital investment, not into a property-owning, largely foreign-owned middle class.

Radhika Desai:

And I would just like to make one final point on the question of how to characterize the Chinese economy and the Chinese state. It’s not just important to say that the state controls the economy, but whose state is it? the way to look at it is that in the United States we have essentially a state that is controlled by the big corporations, which in our time have become extremely financialized corporations, so that they steer the United States economy, essentially, toward more and more debt and less and less production.

Whereas that is not the case in China and the question of who is making use of the word autonomy. The autonomy refers to the fact that it is not subservient to any section of society, but seeks to achieve the welfare of society as a whole and to increase its productive capacity. I think it’s also important that you pay attention to the policy-making process in China. is an example of what you might call substantive democracy. It delivers substantive results for the entire Chinese population. In that sense, it delivers improvements in the quality of life for all the people. And so it’s a democratic system in a sense, but it’s also a country that actually has procedures of policy making, experimentation, design, and choice and so on. Which are extremely important. And these are fundamental aspects of democracy. So when Western countries characterize China as authoritarian, they’re actually fundamentally misrepresenting the character of the Chinese system and the way when it works, because they’re in a sense just equating democracy with a system, whereas China has multiple political parties, but a system of competitive elections between different political parties.

There are other models of democracy and China is another model of democracy.Indeed, in China they have recently developed a new term for it. They call it whole process democracy, and it really involves multiple levels of consultation with the people, going down to the most basic village and township level, and then all the way up the chain.

And I think this process works because the other remarkable thing about the CPC leadership is that they have the ability to change direction pragmatically. If something is not working, then it evaluates what it tried to do, why it has failed. And then they reverse course. So I think we will see several examples of that as we talk. Michael, you want to add something?

Michael Hudson:

One thing about democracy, the definition of democracy traditionally is to prevent an allegory from developing. There’s only one way to prevent an oligarchy from developing as people get richer and richer, and that’s to have a strong state. The role of a strong state is to prevent an oligarchy from developing. That’s why the oligarchy in America and Europe is libertarian, which means get rid of the government, because a government is strong enough to prevent us from gouging the economy, to prevent us from taking over the economy. So you need a strong central government and order to have a democracy. Americans call that socialism. They say that’s the opposite of democracy, which is a state that’s loyal to the United States and follows U.S. policies. And let the US banks financialize the economy.

-1.jpg?fit=300%2C169&ssl=1)