Crisis of China property giant Evergrande: Has China’s Property Bubble Finally Popped?

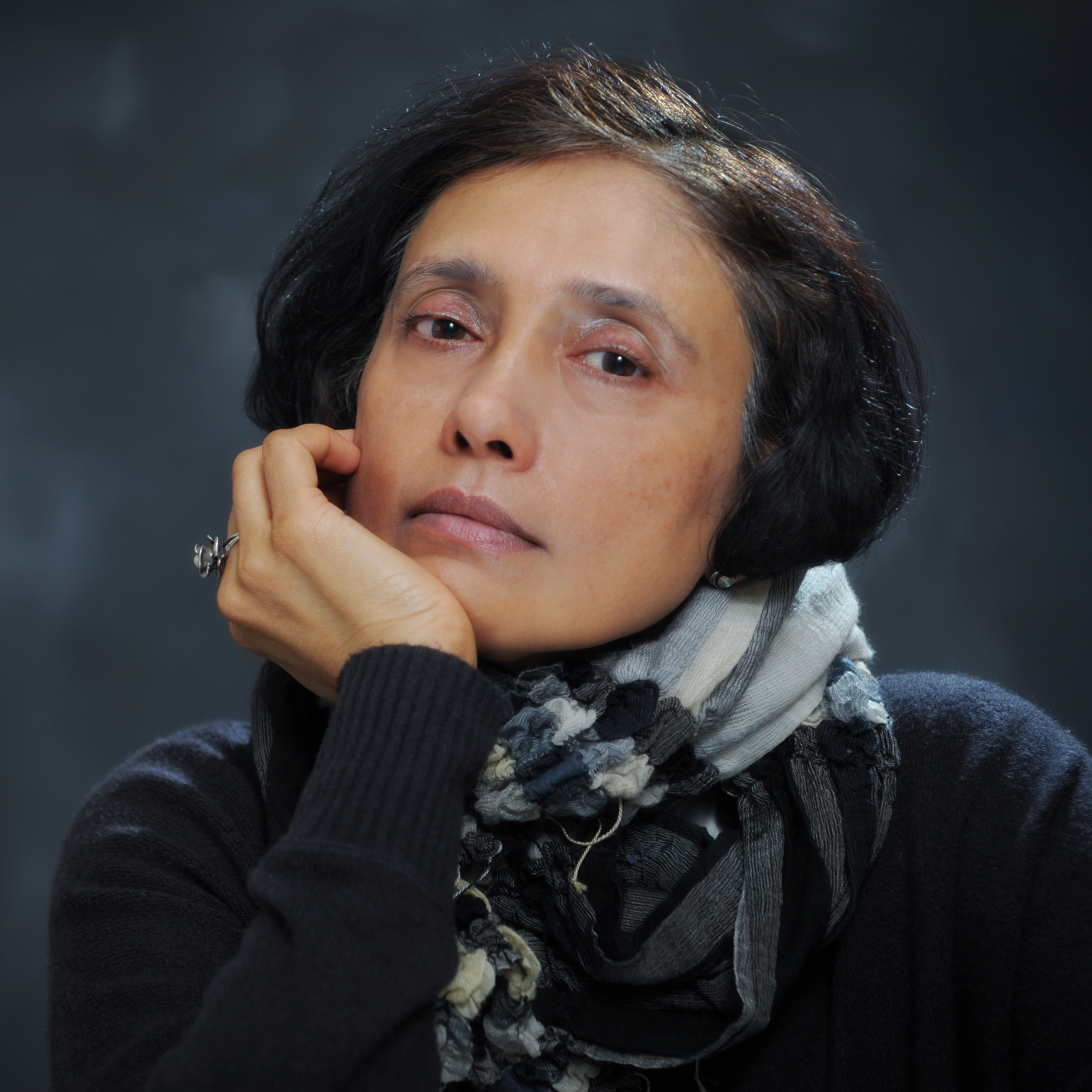

Last month, an intellectually stimulating conversation on China’s economy took place among three leading scholars: Radhika Desai, the director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba; Michael Hudson, professor of Economics at the University of Missouri; and Mick Dunford, emeritus Professor at the University of Sussex. This is part II of a conversation series on China’s economy.

Radhika Desai:

let’s do the next topic, which is the property bubble. So, mick, do you want to start us off about the property bubble?

Mick Dunford:

The story started with the housing reform after 1988, when China moved from a welfare system to a commodity system. And then in 1998, it actually privatized down way housing. It took the view that housing should be provided as a commodity by developers. And in 2003 that was confirmed. And from that point on, you saw a very, very substantial growth in the number of developers, many of whom, the vast majority of whom were private developers. So in a sense, they moved to a fundamentally market system. They had to make certain adjustments very quickly because they found that while the quality of housing and the amount of housing space for a person was going up, these developers were targeting their housing to more affluent groups.

There was an underprovision of housing for middle-income groups and for low-income groups. And there was gradually, as you saw over the years, more and more attention paid to the provision of low-cost housing and low-cost rental housing. And in fact, in the current 5-year plan, 25% of all housing is supposed to be basically low-cost housing. The important point is that this problem has arisen in a system that has actually been liberalized in accordance with the recommendations that were made by the World Bank in 1993.

In other words, it is an example of a liberalized, predominantly market, private led system where these difficulties and these problems have merged.

That’s the first thing I want to say. And I obviously to address the housing needs, China has had to move back significantly over time in the direction of providing low-cost housing to meet the housing needs of the Chinese people. But basically, in August 2020, the government became very, very concerned about, on the one hand, rising housing prices and, on the other hand, the explosion of leverage and the fact that the liabilities of many of these developers were substantially exceeding their assets. And the other line on this chart is a line that shows house prices in the United States. Of course, it was the crash, the prices in the subprime market, that in a sense triggered the financial crisis. So China, first of all, is absolutely determined that it should not face the kind of problem that was created by the liberalized housing system in the United States.

So that’s basically the first thing I want to say. I think if you want, I can say something about the case of ever growing. But basically what China did in 2020 was they introduced what they called the three red lines, which were basically designed to reduce financial risks, but it had a number of consequences because it deflated the housing market to some extent. Housing prices started to fall, some of these developers found themselves in a situation where their liabilities significantly exceeded their assets. There was a decline in residential investment. But to some extent I think this is part of a deliberate objective to basically redirect capital towards, as I said, high productivity activities and away from activities, particularly the speculative side of the housing market.

Michael Hudson:

What I’d like to know is the background for this is. How much of this housing is owner occupied? And how much is rental a housing? The other question is how much the ratio of housing costs to personal income? In America it’s over 40 % of personal income for housing. What’s the ratio in China? I’d also want to know the debt equity ratio, how much depth on the average for different income groups, relative to the value of housing.

Radhika Desai:

The blue line, which shows the United States housing prices, you can see that they reached a certain peak in 2008 at 150 times the value of their 2010 values, and then they went down to below the 2010 level. But the U.S. monetary policy, the Federal Reserve policy, it’s the continuation of the regulated financial sector, the easy money policy, which has been applied in a big way with the zero-interest rate policy, with quantitative easing, et cetera, has simply led to a new real estate boom, where real estate prices have reached a peak that is even higher than that of 2007-2008, which was such a disaster.

This was all made possible precisely by increasing housing debt, et cetera. Whereas in China, a big driver of the housing boom was actually people investing their savings in housing. So, logically, it means that the level of debt in the housing market will be comparatively lower. The entities that are in debt are actually the developers. That’s a very different kind of problem than the owners being in debt.

Mick Dunford:

The problem is the indebtedness of the developers and the existence of debts that far exceed the value of their assets.

And the way in which this situation has come about. And as I said, the Chinese government wants to address the financial risks associated with this situation, has done so by introducing these so-called 3 red lines, is also interested in reducing housing prices and is also interested in redirecting finance towards productivity, increasing activities.

So Evergrande is an enormous real estate giant. It has $300 billion in debt. It has $20 billion in overseas debt, and its assets, according to its accounts at the end of the last quarter of last year, were $242 billion. And 90% of those assets are in mainland China. Its debt-asset ratio was 84.7%, and the three red lines set a limit of 70%.

So it’s well above the red line. In 2021, it defaulted. And then in January this year, it was ordered to liquidate after the international creditors and the company failed to agree on a restructuring plan. In September last year, by the way, its chairman, Xu Jiayin, was placed under coercive measures on suspicion of unspecified crimes. Basically, it was a Hong Kong court that called in the liquidators. And the reason was that outside of China, Evergrande looked like a massively profitable distressed debt trading opportunity. There was 19 billion in defaulted offshore bonds with very substantial assets. And initially there was a view that the Chinese government might prop up the real estate market. So a lot of us and European hedge funds basically piled into the debt, expecting quite large payouts. But it seems that these negotiations were to some extent controlled by a risk management committee in Guangdong. And the authorities basically were very, very reluctant to allow offshore claimants to secure onshore income and onshore assets.

In fact, to stop the misuse of funds, I think about ten local Chinese provinces actually took control of the pre-sale revenues. They put it in escrow accounts. And the idea was that this money should basically be prioritized to make sure that the houses of the people who had paid deposits for houses were actually built, and the people who had done the work of building houses were basically paid, and then we saw the value of these offshore bonds collapse very rapidly indeed.

And I think that to some extent explains the concerns of the international financial market about the difficulties of this particular case.

But I think it’s clear that China is basically turning to deflate this sector and to put an end to this speculative real estate market as much as possible and to redirect capital into productivity-enhancing, essentially the industrial sector.

These creditors, bondholders and also other creditors, basically shareholders, are going to take a very big haircut.

Radhika Desai:

Exactly. I think this is the key, that there will be an imposition of haircuts on the rich and powerful, not just subjecting ordinary people to repossession of their home, which they should have access to.

So, as Mick said, the Chinese government is doing everything possible to make sure that the ordinary buyers who bought these houses do not lose out, which is the opposite of what was done in trying to solve the housing and credit bubble in the United States.

The Chinese government is well aware that the whole thing that caused this whole housing bubble is in good part a product of the fact that when relations between China and the West were much better, China accepted some advice from the World Bank. And this is partly a result of that and the kind of deregulation that the World Bank had suggested. But it is very clear now that relations between China and the West are not good. In fact, they are anything but good. China is unlikely to be once bitten twice shy. Even if they were good, and now that they’re not good, they will be.

And China is clear. Looking at distinctively pragmatic, socialistic ways out, and you see in the new, they are addressed to the NPC by the Premier that social housing has become a major priority, not building houses for private ownership, but rather building houses that will be kept in the public sector and rented out at affordable rates. And I think that is a really important thing. Really the way to go. And finally, I would say that the housing bubble in Japan and the housing bubble in the United States were bound to have very different consequences, partly because of two reasons, mainly number one, the nature of the financial systems were very different.

In the case of Japan, the financial system was transformed from one that resembled China’s financial system to one that resembled the U.S. financial system much more. And Japan has continued that transformation and has suffered as a result. I would say, in short, Japan has really been the price of keeping its capital economy capitalist. So, in many ways, so is the United States. The second reason is that, funnily enough, one of the effects of the Plaza Accord was that by the time the Plaza Accord came along, Japan was no longer interested in buying our Treasuries. And as a result, the United States essentially restricted its access to the U.S. markets to a much greater extent. And so Japan essentially lost those export markets, it did not do what China is able to do. It may not have been able to do what China is able to do as a capitalist country, which is to massively redirect the incentives for production away from exports and toward the domestic market, including the investment market.

Mick Dunford:

So I think the japanification course is not one that China will follow, that China will actually address this, need to innovate and transform its industrial system, in order in a sense, address the problems that are associated with the earlier drivers of Chinese development.

-1.jpg?fit=300%2C169&ssl=1)