Both China and the World Should Treat China As Global Trade Champion

Explaining China’s Booming Automotive Exports

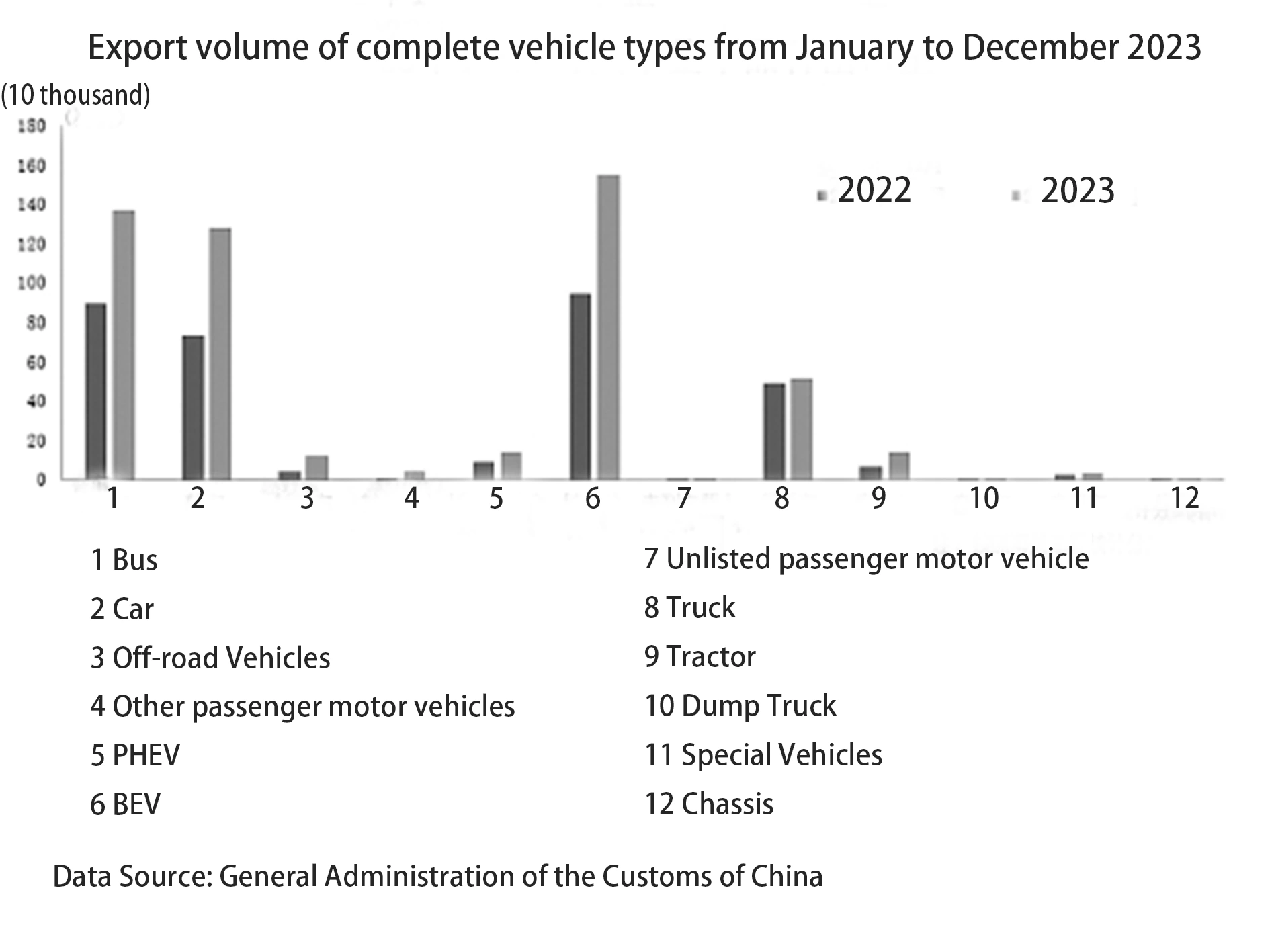

In recent years, the most significant change in China’s foreign trade landscape has been in the automotive sector. According to data from the General Administration of Customs, China exported 5.221 million vehicles (including chassis) in 2023, marking a year-on-year increase of 57.4%. Looking back to 2020, only 1.081 million vehicles were exported that year, representing a staggering 383% growth over three years. Data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) shows that vehicle exports reached 4.91 million units in 2023, a year-on-year increase of 57.9%.

The discrepancy between the data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) and the General Administration of Customs primarily stems from differences in statistical standards. One factor is that customs statistics include chassis exports, which cover vehicles assembled overseas. However, the main difference lies in the fact that customs data includes vehicles released to bonded zones outside customs areas awaiting shipment, while CAAM only counts vehicles that have actually left the port. Based on customs data, China exported 5.859 million vehicles in 2024, maintaining a year-on-year growth rate of 19.3% and retaining its position as the world’s largest vehicle exporter.

Automobiles, with their high unit prices, wield significant global influence. In 2023, China’s vehicle export value reached $101.61 billion, a year-on-year increase of 68.9%. The four major categories were buses, cars, BEVs, and trucks. Exports of fuel-powered vehicles also experienced rapid growth, indicating that the surge is not solely driven by electric vehicles.

The core reason for the explosive growth in vehicle exports is that Chinese automobiles, whether electric or fuel-powered, offer superior cost-performance ratios compared to those from other countries. However, China’s automotive industry has yet to fully demonstrate its strength on the international stage. For instance, the absolute scale of exports for PHEVs, one of China’s strongest categories, remains relatively low, indicating substantial room for growth.

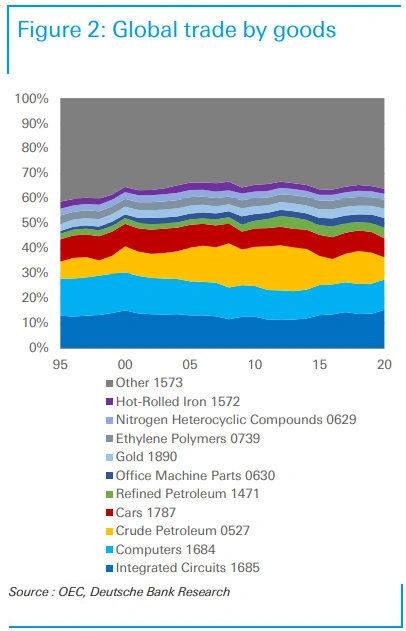

The proportion of the amount of various commodities in global merchandise trade. The numbers in the figure are commodity codes.

The proportion of the amount of various commodities in global merchandise trade. The numbers in the figure are commodity codes.

Automobiles are not ordinary commodities; they are highly complex technologically and even serve as one of the most significant representative products of a nation’s image. In international trade, the top four categories by value are integrated circuits, computers, crude petroleum, and automobiles, which are significantly higher than other categories. Integrated circuits are somewhat unique, as they require multiple processes such as wafer fabrication, FAB, packaging, testing, integration, and sales, involving numerous intermediate goods in international trade. As a result, their international trade value is substantially larger than their final sales value. For example, in 2020, the global trade value of semiconductors was 2.6 trillion, but the final sales value was 2.6 trillion, but the final sales value was 437 billion. Therefore, computers, crude petroleum, and automobiles are the true top three trade categories, with their scales being relatively close.

Chinese automobiles have surpassed their competitors in performance, intelligence, and design, while maintaining a significant advantage in production costs. For instance, when the American electric vehicle startup Rivian disassembled a popular Chinese electric model, they discovered that the Xiaomi SU7, which sells for just over $27,400 (¥200,000) in China, would cost $68500 (¥500,000) to produce in the United States.

When China achieves such a dominant advantage in the automotive trade, it underscores that the country’s trade superiority is not confined to a single industry. Instead, China’s trade advantage has reached a level that was once unimaginable, reflecting its comprehensive strength on the global stage.

China’s Trade Surplus is Redefining Global Trade

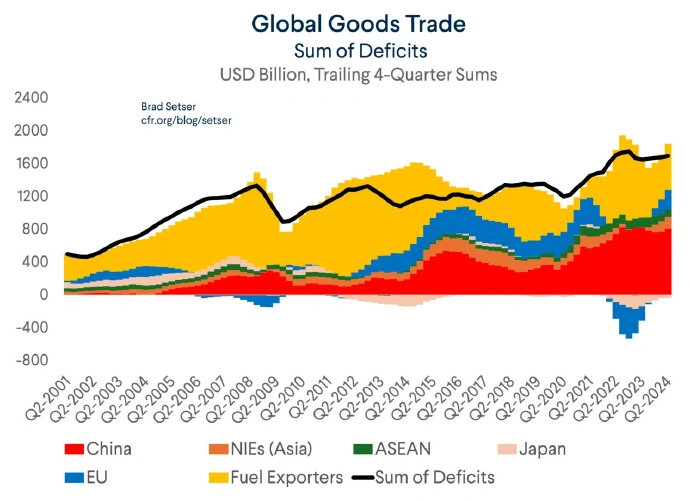

According to a Goldman Sachs report, China’s goods trade surplus as a percentage of global nominal GDP increased to approximately 0.8% in both 2022 and 2023. In 2024, China’s trade surplus reached approximately $1.06 trillion (7.06 trillion yuan), marking another increase of nearly 20%. China’s surplus now approaches 1% of the GDP of all countries globally, signaling the emergence of a structural force. Typically, a country’s surplus or deficit only affects itself, but in China’s case, the global spillover effects of its industries must also be considered. For instance, the GDPs of many countries are based on imports of Chinese goods.

The chart illustrates the evolution of the composition of the world’s major surplus countries from 2001 to the second quarter of 2024. Relying on its manufacturing sector, China’s trade surplus in global trade has surpassed the combined surpluses of oil and natural gas exporting nations. Chinese goods now play a foundational role in the global […]

The chart illustrates the evolution of the composition of the world’s major surplus countries from 2001 to the second quarter of 2024. Relying on its manufacturing sector, China’s trade surplus in global trade has surpassed the combined surpluses of oil and natural gas exporting nations. Chinese goods now play a foundational role in the global […]

Based on the principles of trade, China can now view its imports and exports from a broader global perspective, not only creating conditions for its own economic development but also contributing to the global economy.

When China joined the WTO in 2001 and partially opened its domestic market, some were concerned about the potential impact on its industries. However, China quickly became a dynamic player in global trade, eventually emerging as a champion of free trade, countering the regressive actions of some nations that sought to close off and fragment global markets. Today, many countries, led notably by the United States, are imposing tariffs, anti-dumping investigations, and trade barriers against China. At the same time, several developing countries are engaging in similar tactics, with India’s unreasonable and aggressive measures even surpassing those of the United States.

It is widely accepted that China has been the greatest beneficiary of globalization. However, the current trend of “de-globalization” is specifically targeting the largest beneficiary of globalization, driven in part by fears of China’s growing power.

Against this backdrop, the global expansion of China’s competitive products, such as automobiles, is unlikely to proceed smoothly and will inevitably face various setbacks, resistance, and disruptions. However, we should remain confident in the competitiveness of Chinese goods. Just as China was unafraid of domestic competition when it opened its market, it can also overcome challenges in the global market.

The key lies in deepening our understanding of the foundational role that Chinese goods play in the global economy. In the past, there were many instances where China lacked a clear understanding of this role, habitually adopting a low-profile stance and engaging in price wars, which led to internal competition spilling over into international markets. Macroeconomic policies often emphasized the driving role of exports, and any sign of trouble was habitually met with a devaluation of the yuan. When faced with unreasonable tariffs, trade barriers, and supply chain relocations by other countries, individual companies, with their limited resources, often struggled to resist alone and ultimately made decisions under pressure.

For instance, China’s Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) has long assisted businesses in resolving a wide array of bewildering issues encountered globally. Chinese merchants overseas, despite earning profits, often face various forms of exploitation and, due to their own lack of caution, may become entangled in troubles such as money laundering and tax evasion. The diverse and high-risk nature of overseas markets makes it difficult for them to feel secure even after making profits.

Currently, China’s trade advantage is substantial, providing the conditions to take the lead in establishing stable and reliable international trade rules. Trade should be conducted on our terms, leveraging our formidable strength to ensure fairness, security, sustainability, low risk, and mutual benefit. If the other party is unwilling to comply, there is no rush to pursue profits. Instead, risks should be assessed, and if the risks are too high, it may be better to refrain from proceeding.

China has greatly benefited from joining the WTO, and the principles of the system are quite sound. China not only recognizes these principles but has also implemented them effectively. The most fundamental principle of the WTO is that international trade should involve the strong “taking care of” the weak, with developed countries supporting developing ones. Developing countries are categorized into three groups: least developed, low-income, and general developing, each with different accession conditions, with more support given to the weaker ones. China’s accession terms were the most stringent among developing countries, with some areas being treated as if it were a developed country, agreeing to numerous additional conditions. From the final outcome, China can be considered a fourth category of developing country, but it is still relatively weaker compared to developed nations.

The “Positioning” Issue of China and the World

After many years of actual operation, it has become evident that China has emerged as the absolute and sole strongest player in global trade. Its dominant position even relative to developed countries is astonishing, leading some U.S. politicians to claim that allowing China to join the WTO was a mistake. Various indicators illustrate this shift in strength, with the “concessionary” statements from executives of automotive powerhouses serving as a case in point. However, this has led to a “positioning” issue in both perception and trade practices between China and many countries around the world.

China identifies itself as a developing country and joined the WTO under the status of a “general developing country.” According to the WTO’s “Most Favored Nation” non-discrimination principle, all members should be treated fairly. The privileges of imposing tariffs and market protection are reserved for weaker nations, and these measures cannot be discriminatorily targeted solely at China. Many countries’ actions, such as imposing tariffs and trade barriers on China, violate WTO principles and are specifically aimed at China. While China has the right to counter U.S. unreasonable tariffs and other issues through WTO rulings and may potentially win such cases, this situation highlights the ineffectiveness of the WTO mechanism. The ongoing trade war has rendered the WTO virtually defunct in practice.

If we position ourselves as the “sole strongest player in global trade,” it becomes clear that other countries will no longer accept China’s identity as a “developing country and weaker party” within the WTO framework. Therefore, albeit reluctantly, we must face reality. Continuing to perceive ourselves as the “weaker party” within the WTO system, whether out of genuine belief or an attempt to conceal our strength, no longer aligns with the current reality.

On the other hand, when countries engage in hostile trade behavior against China, although they recognize China as a strong trade power in their motives or subconsciously, they seem to treat China as a weak country in their actions and make various large-scale actions that violate WTO principles at will. This is also a contradiction, a positioning error of various countries, which needs to be corrected just like China’s own positioning error.

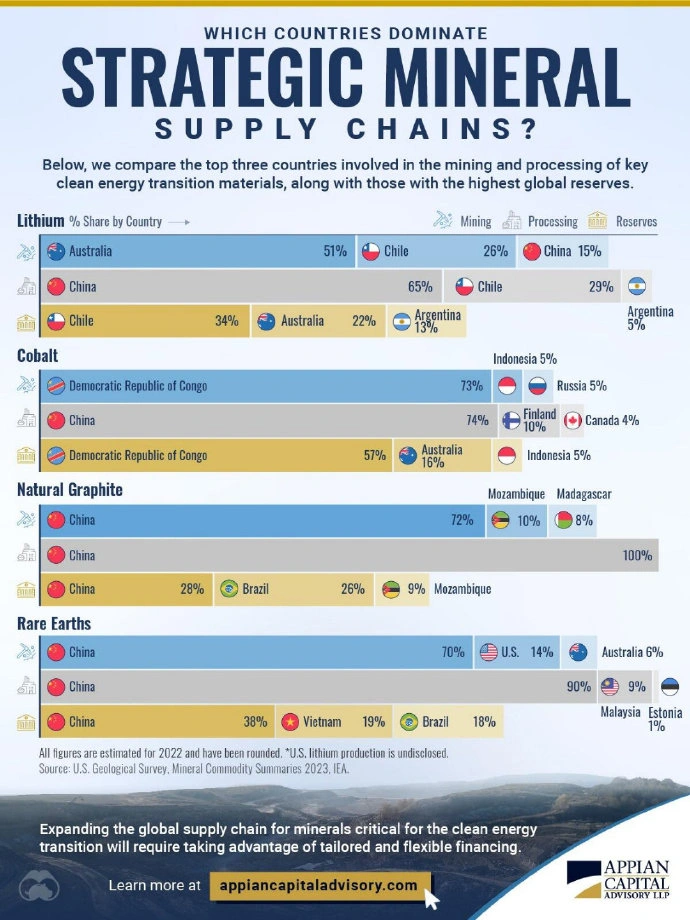

In fact, under the pressure, China has been forced to establish some counterattack mechanisms, which has surprised other countries. Since July 2023, China has successively imposed export controls on key minerals such as gallium, germanium, and graphite. Coupled with the previous rare earth export system, the world has recognized China’s amazing strength, which was mostly unclear in the past. The above figure shows the share strength of various countries in clean energy-related minerals such as lithium, cobalt, natural graphite, and rare earths, respectively, in terms of mineral output share, production and processing share, and reserve share, with only the top three listed. Even in areas where China does not have an advantage in reserves, China has huge production advantages, which has already had a deterrent effect on some countries.

An interesting case is the “psychological positioning” contest between China and India, which, in my view, has undergone a decisive and fundamental shift.

Both China and India previously had misconceptions about their positioning, with India even believing it had leverage in trade negotiations. The prolonged and difficult border talks between the two countries were largely due to India’s insistence that China make territorial concessions; otherwise, India threatened to restrict market access and impose trade penalties on China. This mindset was completely misguided, as it fundamentally misjudged the balance of trade power between the two nations.

China, on the other hand, appeared overly passive, merely calling for a “restoration of friendly relations.” Despite India implementing a series of hostile measures that harmed Chinese companies and citizens, China seemed to take no countermeasures. Even today, there are no direct flights between China and India. Due to India’s visa restrictions, the number of Chinese students in India has dwindled to just seven, while over ten thousand Indian students continue their studies in China without issue.

But reality always plays a decisive role. The Indian side has gradually realized that Chinese goods—especially large-scale manufacturing equipment, active pharmaceutical ingredients, electronic components, and solar cells—are crucial to India’s economy. Even for supply chain relocation, technical support from Chinese workers remains essential. Within India’s economic sectors, there have been proposals to ease visa restrictions and open certain industries to Chinese investment, but these efforts have faced opposition from the diplomatic sector.

In reality, despite India’s hostile attitude toward China—marked by deep antagonism, eagerness to replace China, and harsh trade measures whenever possible—its reliance on Chinese imports continues to grow. India has now become China’s second-largest trade surplus source after the United States.

According to China’s General Administration of Customs, China’s exports to India reached $120.481 billion in 2024, a 2.4% year-over-year increase, while imports from India fell 3.0% to $17.997 billion. This trend sustains an annual trade surplus of over $100 billion. Although Indian statistics report a slightly lower figure, they still indicate a surplus of approximately $90 billion in China’s favor.

The Indian side instinctively believes that “China is making money from India,” treating this as a bargaining chip—assuming that if China wants to continue profiting, it must make concessions on the border issue. However, the reality is quite clear: India desperately wants to curb China’s economic gains but simply has no means to do so. Given this fundamental dynamic, China is actually in a position to impose trade penalties on India and respond accordingly to its aggressive and hostile stance.

In July 2023, the Indian government rejected BYD’s $1 billion proposal to build a second factory (the first being only a small assembly line), seemingly believing that such investments were something China desperately sought from India. However, the tide has since turned.

In April 2024, SAIC’s Indian subsidiary, MG Motor India, accepted an equity investment from JSW Group, selling a 51% stake for 3.5 billion yuan ($490 million). This allowed SAIC to fully recoup its prior investment of 3.2 billion yuan ($450 million). Notably, 8% of the transferred stake was allocated to distributors and employees without investment rights, meaning SAIC still retains control over its 49% share. This directly refutes rumors that SAIC was “forced to sell at a low price.” In 2023, MG Motor India sold 56,000 vehicles, generating approximately 5 billion yuan ($700 million) in revenue. The widely publicized $10 billion valuation was clearly unrealistic, and the $1.5 billion transaction valuation was much more reasonable.

While SAIC’s investment in India has been financially successful without losing control, India’s desire to dominate Chinese investments in industries like automobiles and smartphones is something to be wary of.

India understands that developing its electric vehicle industry is impossible without China, which holds an overwhelming advantage in the supply chain. The Indian side is well aware of this reality. Given the Chinese government’s significant influence over its automakers, India will likely find no room for maneuver in this strategic game.

Market share of mobile phone brands in the Indian market in 2023

Market share of mobile phone brands in the Indian market in 2023

Chinese smartphone and electronics companies have been investing in India for a long time, making the situation even more complex. Chinese smartphone brands now command over 70% of the Indian market, with an increasing number of players entering the space. In 2023, eight of the top ten smartphone brands in India were Chinese, including Poco (a Xiaomi sub-brand) and Infinix and Tecno (both Transsion sub-brands).

Beyond the top ten, other brands like Motorola, Honor, and Nothing have also seen significant growth. By 2024, vivo had risen to the top spot in India with a 19% market share, followed by Xiaomi at 17%. Samsung ranked third with 16%, while OPPO and realme held the fourth and fifth positions with 12% and 11% market shares, respectively.

Chinese smartphone companies dominating the major markets of the world’s two most populous countries is a significant achievement. However, from India’s perspective, the fact that Chinese brands control such a large share of its domestic market is difficult to accept given its own industrial ambitions.

From a financial standpoint, expanding into India has proven profitable for Chinese smartphone manufacturers—otherwise, so many companies wouldn’t have rushed in. However, in terms of technology transfer, Chinese firms have helped India establish a moderately developed smartphone supply chain. This, in turn, has given India the confidence to pursue a larger role in global manufacturing. Emboldened by this progress, India has aligned itself with the U.S. in trade conflicts, dreaming of replacing China in the global supply chain.

Industries such as automobiles and smartphones hold significant strategic value, and India’s market potential is immense. For Chinese companies, the challenge is twofold: on one hand, they must enter the market and secure a substantial share; on the other, they must prevent a hostile and ambitious rival from growing into a formidable competitor.

This task cannot be approached with a weak mindset—it requires a strong, strategic outlook, with a comprehensive assessment and a well-coordinated trade strategy toward India. China holds a massive industrial advantage, and India’s development is inherently tied to trade with China. Meanwhile, China has no rigid demand for Indian products. While the trade surplus is substantial, it is merely an added benefit rather than a necessity. With this foundation in place, China has nothing to lose in its trade game with India—it can only win.

Beyond India, Chinese automakers are also eyeing investments in multiple countries around the world. Leading companies like BYD, Chery, and Geely, which have seen strong growth, have already established factories or investment plans in countries such as Thailand, Turkey, Italy, and Spain.

Erdogan witnessed BYD signing an investment agreement in Türkiye

Erdogan witnessed BYD signing an investment agreement in Türkiye

If companies are too cautious, they may only look to export finished vehicles, but this approach is not the norm for global automakers. Countries with sufficient economic strength, a sizable consumer base with purchasing power, and some manufacturing capabilities tend to require automakers to set up local production. This is a reasonable expectation.

If Chinese automakers aspire to join the ranks of the top five or top ten global car companies, they must follow the example of their global counterparts—establishing wholly-owned subsidiaries, joint ventures, and strategic partnerships in multiple countries, employing various methods to capture market share.

At this stage, the global community will recognize China’s manufacturing, foreign trade, and automotive strengths. It will no longer be necessary or possible for China to continue approaching global trade development within the WTO framework from a “weaker” position.

We will, of course, continue to champion free trade, confidently refuting the regressive actions of the West in attempting to close off and fragment the global market. However, in trade dealings, it is essential to adopt the mindset of a strong player, understanding the “weaker” mentality of the other party. This allows for negotiating trade terms that are acceptable to all parties and enables entry into markets that the other side wishes to protect.

We need to make the other party acknowledge their “weaker” position in negotiations, public relations, and trade exchanges. It is unacceptable for them to act arrogantly and, under the guise of strength, impose sanctions or threats on China, demanding that we conform to their wishes. This must be firmly opposed, and we must ensure that the other side clearly understands who holds the power. Even some Americans have begun to acknowledge China’s dominance in manufacturing, and other countries are even less of a challenge in this regard.

The key, however, lies with the United States and India—these two major adversaries with the most hostile attitudes. In our confrontations with them, we must not indulge in illusions or politeness. We must stand firm and unyielding.

If the other side acknowledges that their strength is inferior to China’s and that they require China’s support, this is also consistent with the principles of the WTO and free trade. Each country has its own national conditions, so complete openness to free trade is not feasible, which is why trade negotiations are necessary.

China has already fully opened all sectors of its manufacturing industry and placed no restrictions on foreign investment. This is a stance that only a true powerhouse can adopt. With this foundation, we can begin negotiations with any country on the basis of “mutual openness,” ensuring that the terms are fair and equitable for all parties.

The WTO’s most-favored-nation (MFN) principle has been overwhelmed by China’s unparalleled superpower status. No matter what deals others make among themselves, they are always the result of weak countries negotiating with each other. However, when the other side adopts the posture of “you are the unique, unparalleled superpower,” China will have to negotiate with each country individually.

This is the fate of a strong nation, but it also comes with the advantages of being strong. The power to set terms, shape agreements, and dictate the framework of negotiations is a privilege that comes with such strength.

By understanding the mindset of the other side and recognizing their demands, both the Chinese government and companies must adapt to the new global landscape and adopt the mindset of a strong player. China’s position in global trade needs to be redefined. It’s crucial to rebuild perceptions with important trade partners and competitors, ensuring that China’s role and influence are clearly established.

Whether other countries view China as a terrifying opponent or as an average nation to being suppressed is an incorrect perception. China is the global manufacturing leader and the foundation of the global economy. Any country that wants to develop well must engage in open discussions with China, clearly outlining their requirements while understanding China’s stance. If they wish to access China’s manufacturing market on equal terms, that’s entirely feasible; if the terms are unequal, concerns can be addressed through negotiation and collaboration. The goal should be to find mutually acceptable solutions that allow Chinese manufacturers to enter local markets through exports, wholly-owned subsidiaries, or joint ventures, contributing to local economic prosperity while ensuring the safety and interests of Chinese enterprises.

Editor: Chang Zhangjin

Anonymous

I fully agree with Mr Jing’s views on India. As an Indian I feel like the war with China in 1965 is the only reason there is distrust and hatred towards China. I hope Indians have to let it go and have friendly relations with the economic powerhouse neighbor. This is the best thing for the country and for its development.

Anonymous

China could take advantage of US invitation to set up low to medium level of manufacturing catering to US market needs . By doing so , China will gain more than lost . As we know US industries are hollowed out through decades of off shoring .

NotChasing

“With this foundation in place, China has nothing to lose in its trade game with India—it can only win.”

Yes, I think that is China’s strategy. Simply to put itself in a position where it can’t lose, then let others respond as they like. I really admire that approach.

It would be more satisfying to confront arrogant countries and defeat them, but this is more beautiful. When a Javier Milei comes along and talks how he’s going to cut ties with China, let him do it. If China ensures its relationships are win-win, countries that cut ties with China punish themselves. The most elegant response in that situation is no response.