An Australian View on China and the Emerging Multipolar World

A major factor in world politics over the past few years has been competition imposed by the U.S. on China, the technology and economy of which has risen at an astounding rate. As the dominant hegemon, the U.S. is extremely reluctant to resign its place at the top.

The world is multipolar and transitioning into a more advanced stage of multipolarity, in which hegemonic power is on the decline, while others, and especially China, are on the way up. China does not represent a “replacement” to the U.S., despite some US voices insisting that it does.

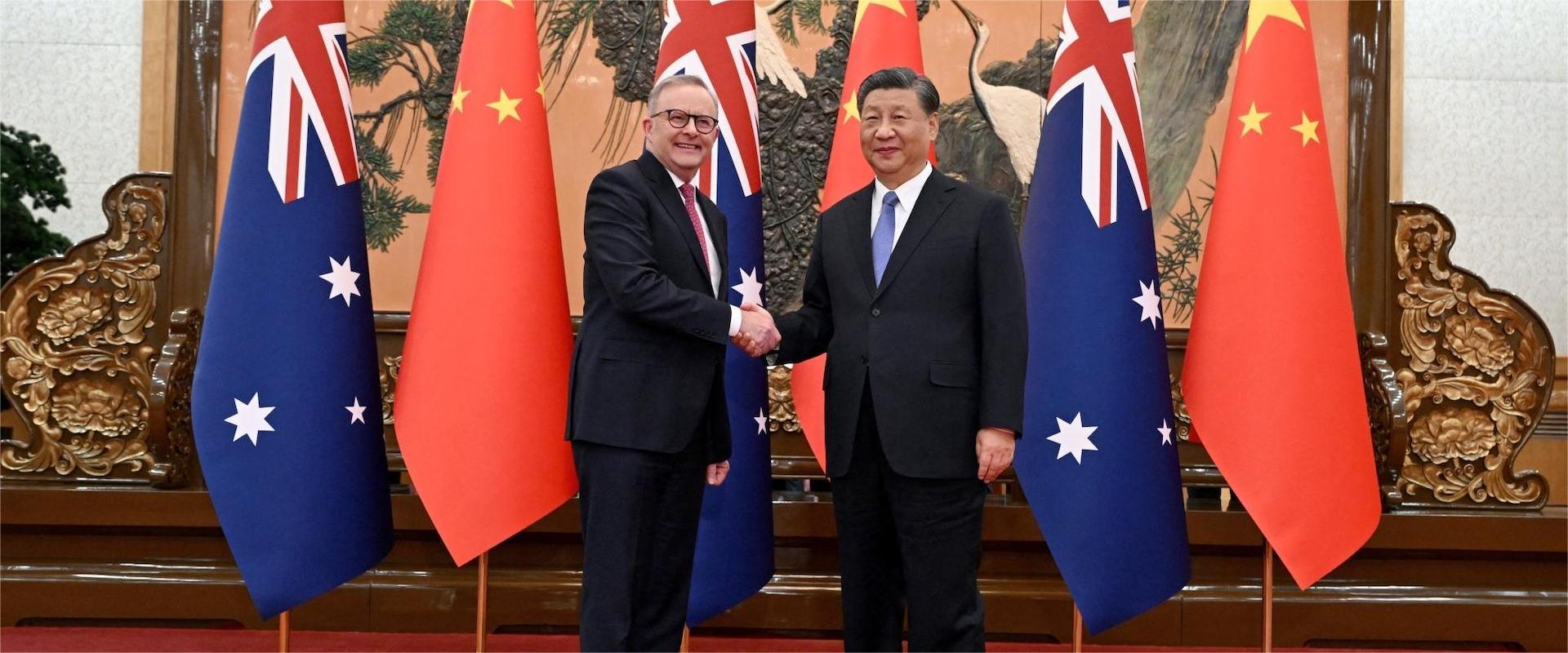

Tensions between Australia and China remain palpable, but recent visits by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to China and Chinese leaders to California contributed to an improvement in relations between China and Australia, on the one hand, and the U.S. on the other. These visits soften geopolitical tensions, but do not completely alleviate them.

This article aims to take up a few issues concerned with the two visits. Specifically looking at the situation through the eyes of an Australian, it makes an analysis of the world situation with a focus on the bilateral relationship between China and Australia.

China-Australia Relations

Australia is starting to transition from an extended period of tense relations with China. A government led by a coalition of two conservative parties ran the country from 2013 to 2022. This coalition produced several prime ministers, the last of them being Scott Morrison, who held the office from 2018 to 2022. The various conservative coalition governments including Morrison had frostier relations with China.

The Morrison government purchased nuclear-powered submarines from the U.S. under an agreement called AUKUS (Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), announced in September 2021. An enormously expensive deal, this potentially signaled a return of British military forces to the Pacific region.

In May 2022, Anthony Albanese was elected Australian Prime Minister, and visited China in November 2023. In its early days, the Albanese government favored a more Western-centric foreign policy. Albanese made numerous overseas visits, meeting with US President Joe Biden and various other Western leaders, but remained cool towards China. Albanese reinvigorated Australia’s support for AUKUS at a meeting with Biden and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in March 2023 in San Diego, California and was insistent about China’s relaxation of trade restrictions on certain commodities, including barley, lobsters and wine, though overall trade with China rose significantly. On the other hand, Albanese also abstained from antagonistic “megaphone diplomacy” aimed at China that Morrison had utilized. The Australian Labor Party (ALP) government initially ignored potential opportunities it could have built with China, but enjoyed a warmer relationship than its predecessor.

Albanese’s visit in November 2023 marked the fiftieth anniversary of a similar visit by Gough Whitlam, who established Australian diplomatic relations with China. Albanese affirmed with Chinese leaders that there were no fundamental conflicts of interest between Australia and China. He also confirmed a strategic partnership agreement reached in 2014 and confirmed that meetings at prime ministerial level would take place every year in China or Australia.

The underlying deciding factor for China-Australia relations is trust. While Morrison’s policy and behavior undermined trust, Albanese tried to rebuild it. Albanese’s visit began the process of rebuilding a broken trust. China remains by far Australia’s largest trading partner and agreements seem to suggest trade in timber and other commodities is deepening. Two-way trade between China and Australia in 2022 was valued at USD 186 billion.

One other highly significant matter appeared to show a revival of mutual trust. In 2015 the conservative government of the Northern Territory approved a 99-year-lease of the Port of Darwin to the Chinese-owned Landbridge group. The deal gave Landbridge complete operational control and 80 percent ownership. Although Landbridge saw Darwin as a trade port, it is very near US and Australian defence facilities. It is hardly surprising that many in Australia saw it as a security matter, with China hawks in Australia believing it could be used as a spy base.

There were several reviews undertaken. Before the May 2022 election, Albanese had stated that he believed “it should never have been sold to the Chinese.” However, a final decision was reached in October 2023 to confirm the lease. Even people who had spoken up against the deal remained silent. I consider this decision is significant for the Australian trust in China it implies.

Popular opinion regarding China in Australia has had peaks and valleys, but I fear there is a deep-seated and unfortunate Sinophobia in Australia that frequently crosses into outright racism. Annual surveys undertaken by the Lowy Institute, based in Sydney, track how Australians feel on international questions, especially China. In June 2023, 52 percent of Australians viewed China as more of a security threat than an economic partner. This is disappointing until we realize that the figure had been 63 percent in 2022 and 2021. This suggests that Sinophobia has reached its peak and is now waning. However, even Albanese’s visit will hardly change the Australian media’s hostile sentiment towards China.

Despite various incentives, the Australian government and public still favors the AUKUS agreement. The Lowy Survey of June 2023 said that no less than 80 percent of Australians still believe the U.S. is crucial for Australia’s future security. Former Prime Minister Paul Keating gave an interview to the prestigious National Press Club in Canberra in March 2023, and denied categorically that China was a threat to Australia.

China-U.S.-Australia Triangle

China-U.S. relations exercise considerable influence on Australia’s attitude towards China. Since 1951 Australia has had a security treaty with the United States (the Australia, New Zealand and United States Security Treaty, ANZUS Treaty), which forms the basis of Australia’s foreign relations. It is possible for Australia to disagree with the United States on major foreign policy matters, but the inherent structure of the ANZUS Treaty makes this difficult.

The Chinese and US leaders recently met outside San Francisco before the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group meeting. During the meeting, China and the U.S. agreed to interface on various matters, including military cooperation and the environment.

An area of importance where Australia has deviated from the U.S. is on policy regarding critical minerals. Access to these materials is a key area of contention between the three nations. At the San Francisco meeting, Australia’s Trade Minister Don Farrell made it clear that, despite the US disapproval, Australia would continue to allow Chinese investment in its critical mineral industry.

The Role of Educational Exchange and People-to-People Relations

We should never forget the role of people-to-people relations. If I could be personal, just for a moment, I’ll never forget that I got a chance to teach in China in 1964 at a time when very few Australians visited the country, let alone lived there. This experience gave me the chance to get to know Chinese people well and listen to their point of view. It made me permanently well disposed both to China and its people.

The readout of the China-U.S. talks on November 15, 2023, has a segment which reads: “The two leaders also encouraged the expansion of educational, student, youth, cultural, sports, and business exchanges.” Being a student in another country provides the chance to experience other cultures, languages, and points of view.

In both Australia and the United States, educational and cultural exchange suffered due to COVID-19 and partisan politics. To quote Australia’s Department of Education: “China remains Australia’s leading market for international students, with 153,239 Chinese students studying at our universities in 2022.” Although this figure is down 11 percent from 2021, there are indicators it will increase again.

Unfortunately, the Confucius Institutes, bodies specifically aimed at the spread of Chinese language and culture, have come under threat in several Western countries, especially the United States, on the totally unreasonable grounds of being national security threats. The improvement in relations brought about by China-Australia and China-U.S. meetings should help relieve this situation. The Confucius Institutes are of great value and the spread of culture and language can only do good. It is crucial in the world today that we understand each other’s cultures and lifestyles.

China in the Wider World

Despite key geopolitical relaxations, international tensions remain high. The Ukraine conflict grinds on, with the much vaunted 2023 counter-offensive by Ukrainian forces yielding minor successes but enormous losses.

The United Nations tells us of a worsening situation when it comes to global hunger. More people are suffering from malnutrition in 2023 than in 2022, with famines in Burkina Faso, Mali, Somalia, and South Sudan. Reasons for the worsening situation include conflict, the climate crisis, and the price of fertilizer.

Chinese relations with the U.S., other Western nations, and many Middle East nations appear to be improving. Several of China’s recent initiatives, including the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Global Civilization Initiative, have achieved concrete results.

In terms of “soft power,” in 2022 the Brand Finance’s Global Soft Power Index ranked China fourth after the United States, Britain, and Germany, China’s highest rank yet. Following Joseph Nye, the index defines soft power as a nation’s ability to influence other actors “through attraction or persuasion rather than coercion,” and the authors commented, “though China’s performance may be a surprise to some in the Western world, it will have been expected across many developing countries.”

The countries of the “West” tend to team up against China. Used to being “number 1,” they are not willing to relinquish their position of dominance. In particular, the United States has an obsession with “exceptionalism” and has convinced itself that, in terms of ideology, military, economic, technological and social progress, it must be the world’s leader. Its response to China’s rise was initially to support it, but under Trump turned against China with wars in the economic and technological spheres. Its most important objective is now to prevent China from overtaking it.

Although the West, Japan and a few others, have tended to align with the West against China, the Global South has adopted a different stance. The composition of the countries participating in the BRI shows that the Global South view China increasingly positively.

What American political scientist John Mearsheimer called “the unipolar moment,” with the U.S. being the only superpower forming the only “pole,” lasted from the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 until 2017. The global geopolitical balance does not indicate the U.S. is on the way out, but does seem to be moving towards a multipolar system, as opposed to a U.S.-dominated hegemony.

The “unipolar moment” has given way to multipolarity. China-related multilateral groupings, especially BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) are eclipsing traditional groups, such as the G7, in importance. The US dollar remains the global reserve currency, but its supremacy looks increasingly shaky and unlikely to last indefinitely.

The West must accept a new multipolar reality where power and influence are distributed amongst other nations. China does not wish to dominate the world, but it does want to share with others. Being one of the great civilizations of the world, that aspiration seems perfectly reasonable to me.

Editor: Leo Cai