China is Gearing Away From the U.S.

Since Trump announced a 60% tariff on China and later added another 10%, along with a 25% tariff on Canada and Mexico, the most vulnerable A-shares seem largely unaffected. Today, A-shares have risen significantly, completely unlike the past when tariffs led to a sharp decline. Life goes on as usual.

Everyone knows that Trump is once again using tariffs as a pretext to pressure other issues, and these so-called “other issues” are often impossible for other countries to fulfill.

For example, demanding that China control fentanyl is an issue that China cannot address; it fundamentally pertains to U.S. domestic problems. Should China send drug enforcement officers to the U.S. to enforce laws? Trump would certainly not allow that.

Similarly, asking Mexico and Canada to manage their borders and stop illegal immigration is ironic, especially since illegal immigrants are already in Canada but still want to enter the U.S. As for Mexico, it’s unfortunate—if it could control the drug lords, it wouldn’t be in its current situation. Trump’s threat to send troops into Mexico to eradicate drug lords is reminiscent of actions taken in the 1980s, which had negligible results.

Other countries cannot manage U.S. affairs, and if Trump cannot handle his own country’s issues, how can he expect others to solve them? It’s laughable.

It’s clear that these actions are merely a performance for his base.

That said, since this situation has arisen, we must look at the long term, regardless of the immediate impact on China.

Goal: Developing Countries

President of Brazil Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, President of China Xi Jinping and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa gesture during the 2023 BRICS Summit at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on August 23, 2023.

President of Brazil Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, President of China Xi Jinping and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa gesture during the 2023 BRICS Summit at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on August 23, 2023.

China is currently in a phase of industrial upgrading. When Americans and Europeans claim that China has overcapacity, is it true? Yes, but it’s not Chinese overcapacity; it’s American and European overcapacity.

According to the law of comparative advantage, Americans and Europeans have higher production costs for industrial goods, so they should shift towards services or agriculture. Meanwhile, China has a lower cost of production for industrial goods, which means China should exchange these for products from the service sectors or agricultural products from Europe and America.

Of course, neither Europeans nor Americans are willing to do this.

China is in a phase of industrial transformation. During the first tariff war in 2017, China’s new energy industry was not yet established, and the auto industry was still in its infancy. From 2014 to 2019, domestic criticism of new energy vehicles was rampant, but eventually, this sector yielded significant results.

Additionally, there has been diversification in foreign trade and settlement methods. Since the last trade war, China has undertaken considerable reforms, gradually shifting its trade from the U.S. and Europe to developing countries, ultimately leading to developing countries exporting goods to the U.S. and Europe.

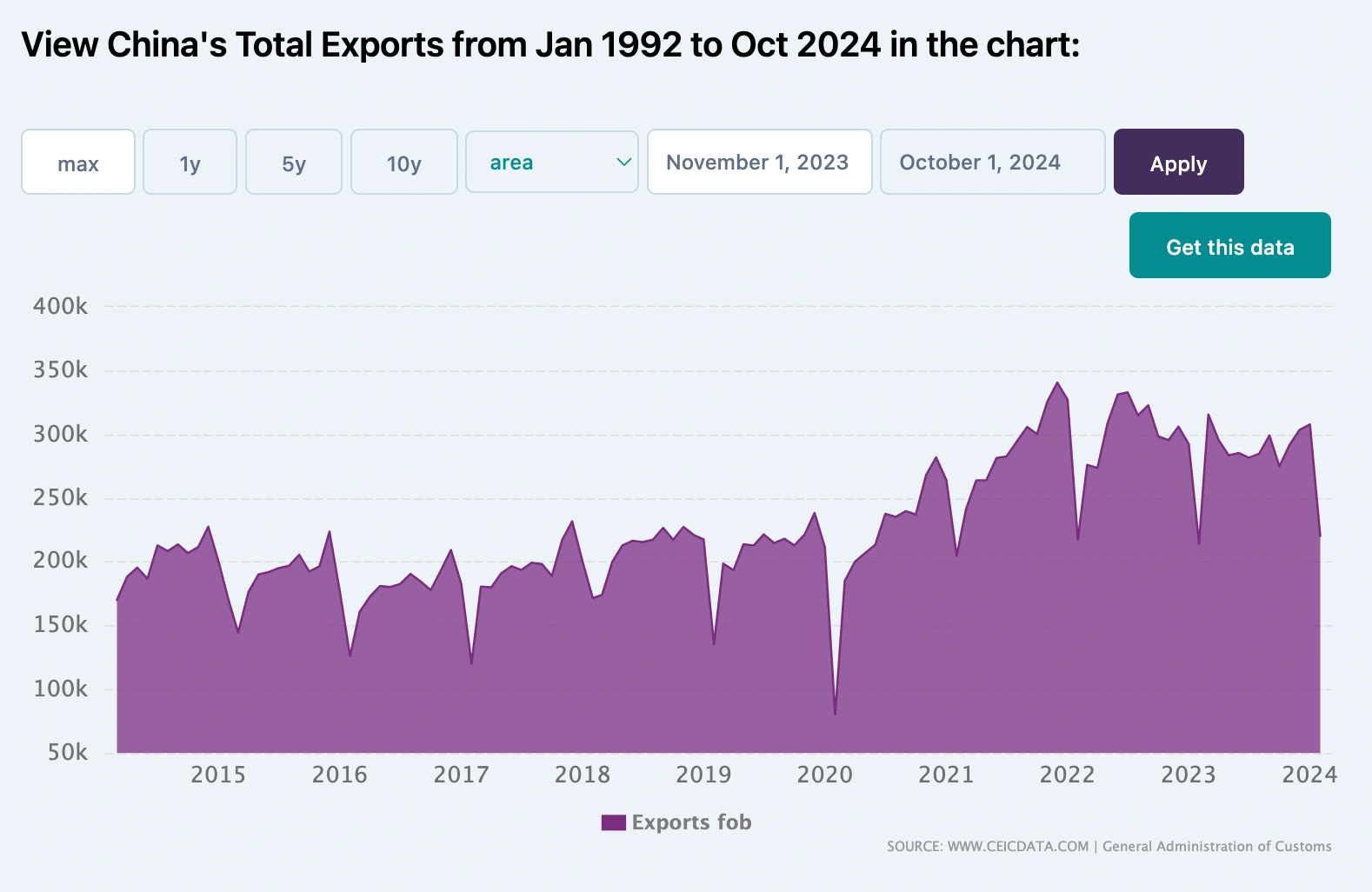

From 2017 to now, measuring China’s export dependence on various countries/regions as a proportion of total exports, by October 2024, China’s export dependence on the U.S. has decreased to 14.6%, down 4.4% from 2017. Exports to the EU and Japan have also dropped to 14.6% and 4.3%, respectively, both down 1.8% from 2017.

Export dependence on countries and regions along the Belt and Road has risen to 45.6%, a significant increase of 17.6% since 2017, with dependence on ASEAN rising to 16.1%, up 3.8% from 2017.

In terms of payment for goods trade, in 2023, the total amount of cross-border RMB transactions for goods trade reached 10.7 trillion yuan, a year-on-year increase of 34.9%. This accounted for 24.8% of the total cross-border payment amount in both foreign and domestic currencies, up 6.6 percentage points from 2022.

Among these, the total RMB cross-border payment amount for general trade was 6.8 trillion yuan, up 34.8% year-on-year; for processing trade, it was 1.6 trillion yuan, up 8.9%. From January to August 2024, the total RMB cross-border payment for goods trade reached 7.9 trillion yuan, a year-on-year increase of 16.8%, accounting for 26.5% of the total cross-border payment amount, up 1.7 percentage points from the entire year of 2023.

At the same time, China has increased its efforts to replace the dollar in international trade.

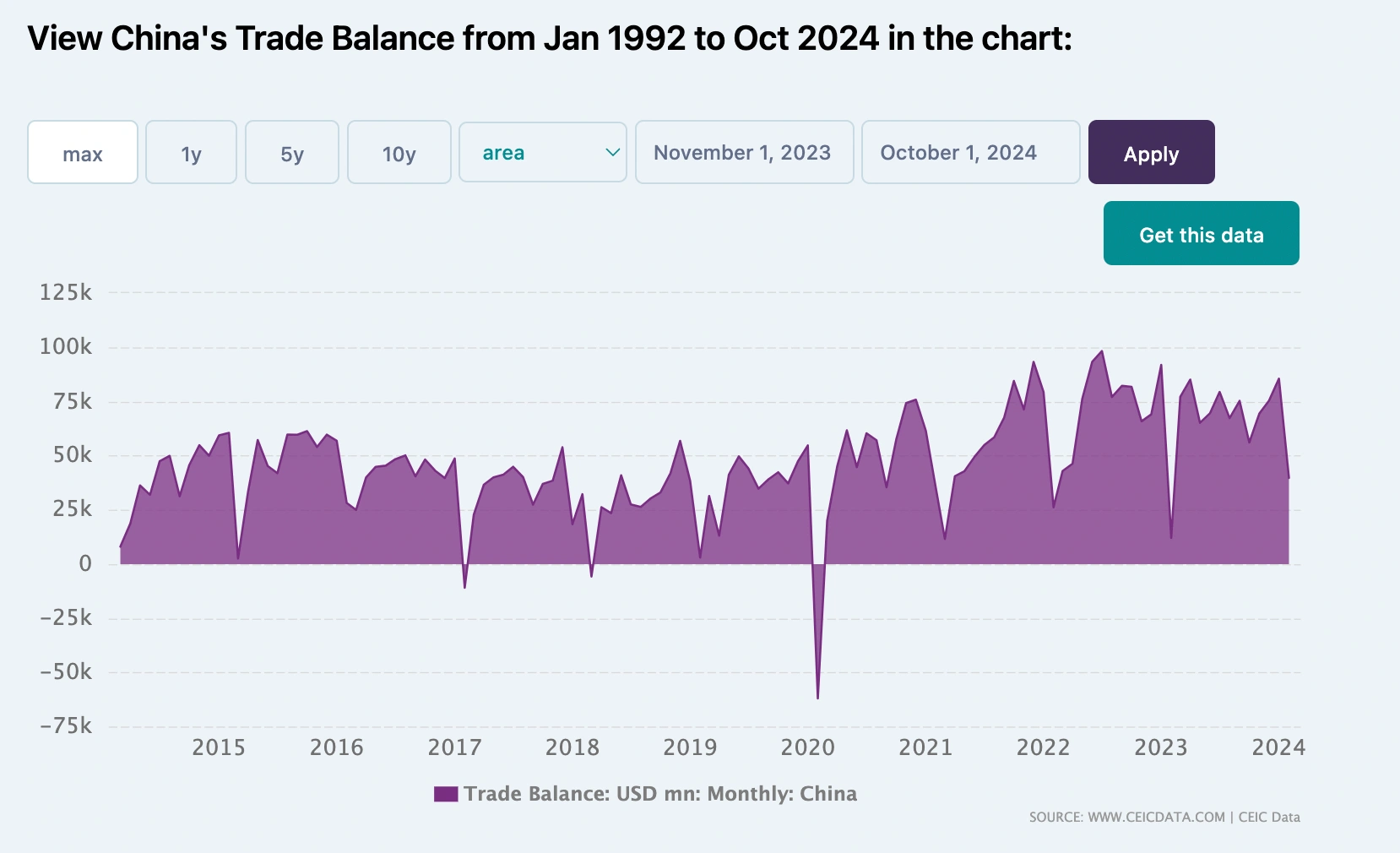

Looking at the trade balance compared to the first trade war in 2017, China’s trade surplus has not only not diminished but has actually expanded. China now has plenty of dollars and significantly improved its adjustment capacity compared to 2017, with overall export amounts also much higher than in 2017.

Currently, there are two directions: one is debt replacement for developing countries, and the other is developing trade with developing countries.

Debt Substitution for Developing Countries

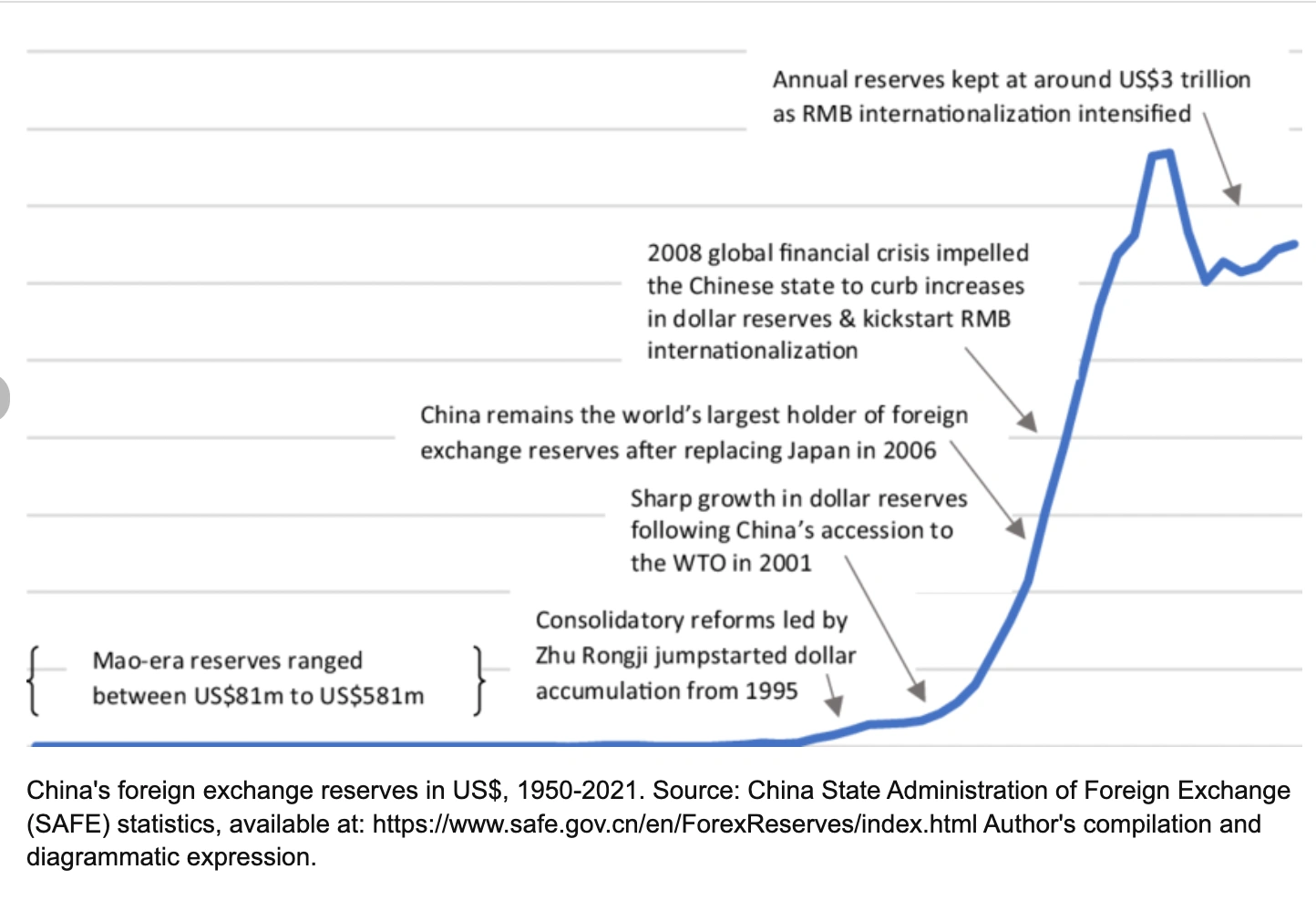

Currently, although China has ample foreign exchange reserves, most developing countries face ongoing deficits and significant dollar debts. While some in China joke that the dollar is just green paper, for these countries, it represents real debt. They are burdened by dollar liabilities, especially as U.S. treasury rates rise, compounded by the tidal effects of the dollar, which creates a heavy burden for many nations.

China holds a significant amount of dollars but retaining them poses strong risks: one never knows when the U.S. might impose sudden sanctions, turning those dollars into worthless paper, as seen with Russia.

To alleviate the debt burden of developing countries, we could consider substituting their dollar debts. For example, if Country A owes dollar debt, we could lend them dollars to pay off their debts, converting those debts into yuan-denominated liabilities. This alleviates Country A’s debt burden and prevents some countries from being driven to sell domestic assets to pay off creditors.

At the same time, it reduces the dollar risks for China.

Moreover, with plenty of dollars on hand, we can issue dollar-denominated bonds. The U.S. loves dollars, so let’s give them what they want, thereby weakening their financial influence.

Of course, the U.S. cannot remain indifferent. However, there are three points to consider: first, this is a transitional period between Trump and Biden, during which the situation is quite chaotic—better to act first.

Second, with Trump’s personality, he might mistakenly view the return of dollars to the U.S. as a positive outcome.

Third, and most importantly, any measure that weakens dollar liquidity damages U.S. dollar hegemony itself. Whether it’s threatening other nations to avoid using Chinese dollars or restricting China’s ability to settle dollar transactions, these actions can ultimately threaten the dollar’s liquidity and undermine its hegemony.

Trade Substitution for Developing Countries

I have repeatedly emphasized that the future of foreign trade development will be in developing countries, not in developed ones.

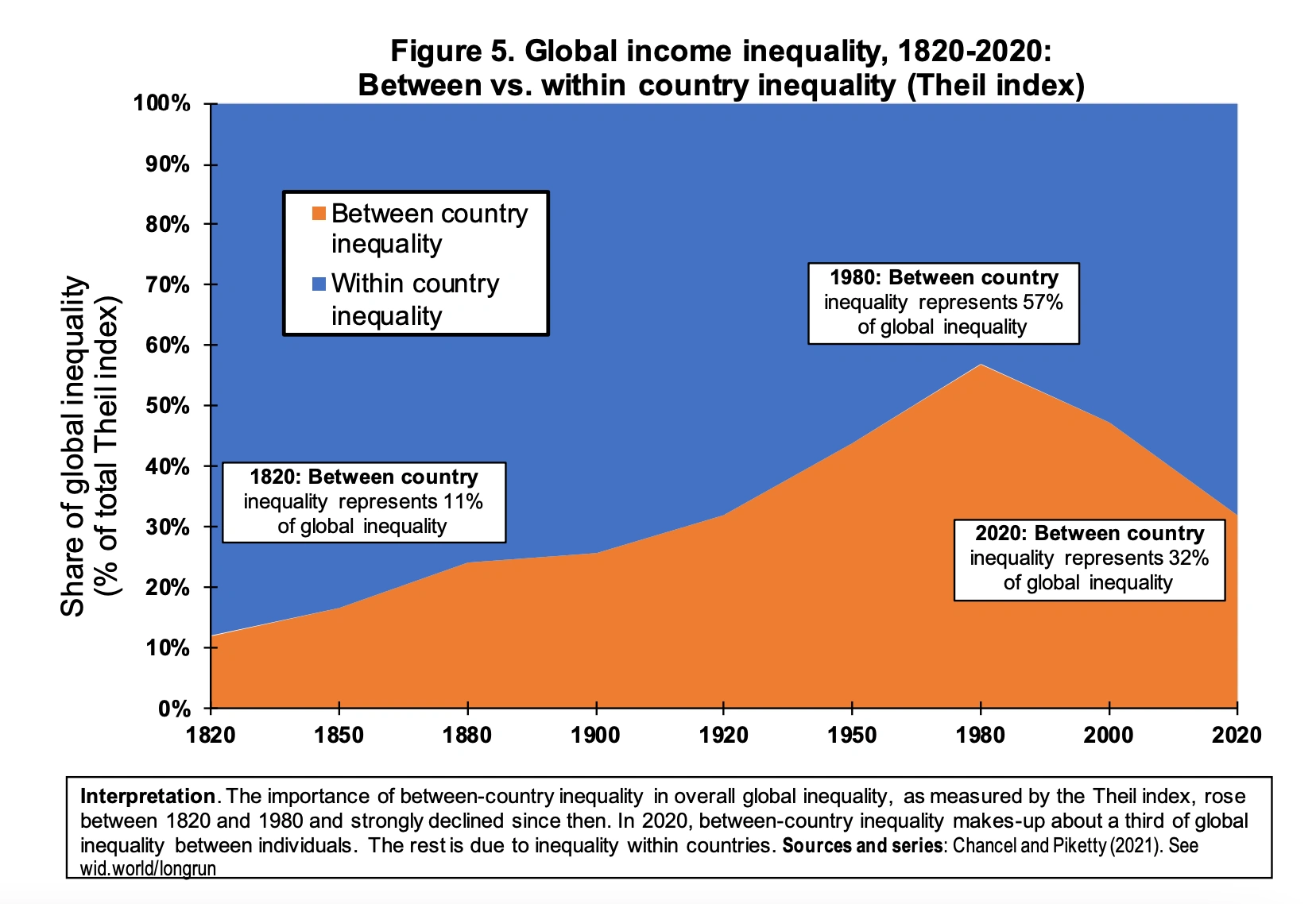

I first realized this when I saw a chart from the World Inequality Lab’s 2022 report, which showed that since the Reagan era, global inequality has shifted from between countries to within countries. Developing nations are progressing more rapidly, while issues within developed countries are increasing, with the turning point occurring in 1980.

The transition from “inequality between countries” to “inequality within countries” is partly due to Reagan’s neoliberal policies. However, fundamentally, Reagan merely accelerated this phenomenon; the root issue lies in the diffusion of information and wealth.

The first steam locomotive railway was the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825, while China’s first railway, the Tangxu Railway, was constructed in 1881—56 years later. The first modern automobile was invented by Karl Benz in 1886, while China produced its first car in 1931—45 years later. Now, however, all new technologies are spreading globally within a decade, such as mobile communication technology, smartphones, and mobile payments.

For instance, in many African countries, people may not have bank accounts but do have mobile payment accounts, like Kenya’s M-Pesa and South Africa’s SnapScan and Zapper.

In Kenya, for example, 75% of the population uses digital payments, while South Africa has 70.5%, Ghana 63.7%, Gabon 62.3%, and Namibia 58.5%. The rapid spread of such technologies greatly benefits commerce.

Similarly, renewable energy is advancing in Africa faster than many expect. Despite some regions lacking basic roads and power grids, and experiencing frequent outages and severe fuel shortages, they can still import second-hand solar panels from China, set up charging devices, and buy renewable energy rickshaws to be self-sufficient. If they lack funds, they can use charging stations as collateral for loans or rentals, effectively establishing a financial system.

This was once unimaginable.

Since then, the diffusion of productivity has accelerated, influenced by two key events: the post-World War II decolonization and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, as well as the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s.

Decolonization allowed countries to truly control their destinies, enabling some formerly colonized nations to manage their internal politics instead of merely serving as sources of raw materials and markets for other countries. For instance, the Tata Group in India began producing commercial vehicles in partnership with Mercedes in 1954, while China produced the Liberation truck through cooperation with the Soviet Union.

At this point, there was information diffusion, but developing countries still lacked a crucial element: capital.

As shown in the chart, China’s foreign exchange reserves peaked at $483 million in 1969. Throughout the late 1970s, they remained below $1 billion.

Many wonder why South Korea developed so quickly. During the Vietnam War, South Korea accumulated substantial foreign exchange reserves, with U.S. aid totaling $928 million from 1965 to 1970—of which nearly $546 million directly benefited South Koreans. This doesn’t include the significant number of South Koreans sent abroad for labor during Park Chung-hee’s era.

South Korea’s population was only 1/28th that of China, meaning the blood of Vietnamese people helped forge South Korea’s economic rise, similar to how the Korean War contributed to Japan’s rise.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the direct peg of the dollar to gold made it difficult for dollars to circulate, as gold’s value was paramount.

After the collapse of this system, especially during the neoliberal era, the dollar, decoupled from gold, lost its previous value. To achieve higher returns, American capital was forced to invest heavily abroad; these investments allowed American capital to enjoy the benefits of developing countries while also helping those countries establish modern industrial systems.

We can observe the resilience of current developing countries: after the real estate crisis in Vietnam, Saigon Commercial Bank faced significant bad debts, leading Vietnam to use a quarter of its foreign exchange reserves to fill the gap. This situation marked a stark turnaround from earlier optimistic views of Vietnam.

However, the reality is that the economic growth rate for the first nine months of 2024 is expected to reach 6.82%, despite the U.S. significantly raising interest rates.

Similarly, despite persistent pessimism about India, the reality is that Modi’s projections of surpassing Japan by 2025 are genuinely feasible. In the first half of this year, India’s GDP was $1.8696 trillion, compared to Japan’s $1.9612 trillion—a close margin, making India’s rise to the third-largest economy no longer just a dream.

The truly struggling nations are the likes of Germany, the UK, and France—U.S. allies. Despite some Chinese economists, such as Fu Peng, previously boasting about Japan’s economy, recent data from Japan’s Cabinet Office indicates that its 2024 GDP growth rate is projected to drop to 0.9%.

“This is far from the ‘takeoff of the Japanese economy.’ Moreover, Japan’s key industries, such as automobiles, are currently under siege. With a bunch of financial jargon like ‘Japanese stocks are rising’ and ‘short-term interest rates are lower than long-term rates,’ it seems unlikely to boost the Japanese economy. However, Japan is experiencing significant inflation, especially in asset prices.

By the way, regarding the current situation in India, since the last agreement between China and India, I made a prediction on October 22: guess what? On November 21, Modi’s most important ally, Indian billionaire Adani, encountered problems.”

It’s clear that any slight movement reveals what the Americans intend to do. Unfortunately, it’s too late; Biden is on his way out, and the Democrats’ tricks are reaching their limits.

I’d like to remind everyone: the overarching trend favors developing countries. Whether you’re involved in imports, exports, investments, studying abroad, or anything else, it’s wise to use this as a reference point.