The post EU’s Weakness Stops It from Confronting Trump to the End first appeared on China Academy.

]]>Setting aside the emotional reactions, the pressing issue is how to respond to Trump’s tariff stick. Since Trump took office, the Chinese government has been assessing the scope and intensity of the tariff war. The imposition of reciprocal tariffs and a series of accompanying measures are clearly the results of strategic planning, rather than mere retaliation. Other economies have also made their own judgments regarding Trump’s tariffs. For instance, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s PR acumen is one reason why U.S. tariffs on the UK remain relatively low.

On April 2, Keir Starmer said: “I really do not think it’s sensible to say the first response should be to jump into a trade war with the US”

On April 2, Keir Starmer said: “I really do not think it’s sensible to say the first response should be to jump into a trade war with the US”

It must be noted, however, that some views predicting a U.S. “isolationist lockdown” and a newly formed global supply chain among the rest of the world may be overly optimistic about the roles of countries other than China. The more realistic scenario is that—excluding China and the EU—most other economies are simply negotiating when and how much to concede to the U.S. in trade terms. Israel and Vietnam lowering their own tariffs are early signs of such concessions.

The EU, due to the differing industrial structures and fiscal conditions among its member states, is also unlikely to mount a substantial resistance to U.S. tariffs. This not only means that China may be the only economy capable of standing up to Trump in the long run, but also that the EU, as one of the world’s three primary economic blocs, is standing at a crossroads. Whether the EU chooses to raise tariffs or not, internal political and economic tensions are likely to intensify. In a time when the illusion of EU unity has largely dissipated, whether the Union will continue to unravel is a question worth serious consideration.

In my previous article, I outlined why Trump initiated this tariff war. Analyzing the long arc of his ideological development, it’s clear that tariffs are part of his broader plan to reshape the United States and are one of the key sources of his stubborn confidence. The undeniable decline of U.S. power and Trump’s own advancing age have heightened his sense of urgency, compelling him to adopt more forceful and radical measures in an effort to reverse what he sees as neoliberal globalization’s erosion of American strength. In this respect, Trump is somewhat akin to former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who forcefully dismantled Jewish settlements despite fierce opposition.

Donald Trump on April 2 announced a 10% tariff on all imports but even higher rates on dozens of trading partners including China and the EU.

Donald Trump on April 2 announced a 10% tariff on all imports but even higher rates on dozens of trading partners including China and the EU.

On a technical level, Trump’s confidence in launching the tariff war is based on two factors. First, the tolerance of his core supporters—particularly the MAGA base—toward the economic pain tariffs may cause; and second, the fact that the U.S. dollar still serves as the dominant currency in global trade. The MAGA crowd’s tolerance stems from the fact that they are closely tied to those who have suffered under neoliberal globalization. While tariffs inevitably impact everyday life, their effects are felt differently in globalization hubs like New York or Los Angeles versus in rural Ohio.

A shortage of cheap eggs in Manhattan doesn’t mean people in rural Kentucky will go without. Wall Street’s stock meltdowns have little direct connection to a farmer in Montana. As the Chinese saying goes, “The barefoot people aren’t afraid of those who wear shoes,” meaning that those with little to lose are less fearful in confrontation. This aptly describes the contrast between MAGA supporters and the beneficiaries of neoliberalism.

The second factor is Trump’s exploitation of the global dominance of the U.S. dollar. While his destruction of neoliberal globalization will inevitably wound the dollar’s supremacy, there is a time lag. During this interim, Trump can wage his tariff war while the dollar still retains its role as the dominant global currency. This is why only China and the EU have a real chance at resisting Trump’s tariffs.

In practice, we’ve seen that most countries either remain silent or call for restraint to avoid escalation. As former British Prime Minister Tony Blair put it, “I don’t think it is in the UK’s best interest to retaliate.”

This explains why much of the current media narrative centers on tolerance. Rather than trying to dislodge the dollar, chipping away at Trump’s support base seems like a more achievable goal. A flood of media stories and analyses claim that Americans will suffer deeply under tariffs, with particular focus on the impact on MAGA supporters.

Trump’s “win, win, win” rhetoric is essentially a way to raise this tolerance threshold. It serves a similar function to wartime propaganda and information control, which are used to sustain internal morale and the support of core voters. As more countries cave and offer concessions to the U.S., Trump will gain ample leverage. It’s foreseeable that as this tariff war drags on, global media battles over its narrative will only intensify.

Let’s now return to the realpolitik of global affairs. How many countries can bear the cost of resisting Trump’s tariff war? In theory, that depends on whether other economies can unite in confronting the challenge posed by his tariffs. But in reality, small countries have no choice but to accept the situation as it is. For them, Trump’s tariff war is like a natural disaster.

Singapore as a city-state is a typical example—it must passively absorb the negative externalities exported by Trump’s tariffs. However, for countries like Japan, South Korea, and the UK—those that do have the capacity to deliberate on how to respond to Trump’s tariff war—inaction has also emerged as the preferred choice.

This is primarily because there are few effective alternatives to reciprocal tariffs for those large economies. Not imposing them is not only seen as politically weak but also as a de facto concession. While there are ways to shift some of tariff costs onto American consumers without resorting to reciprocal tariffs, these methods are neither as direct nor as effective—and they often come with significantly higher implementation costs.

In practical terms, refusing to impose reciprocal tariffs is tantamount to direct concessions to the U.S.—and worse, it lowers the bar for future demands from Trump. After all, dismantling neoliberal globalization is his ultimate goal; reducing trade deficits is just one of many surface-level expressions.

For economies considering reciprocal tariffs, they must evaluate three key factors: their trade surplus with the U.S. (exposure level), their domestic economic and fiscal strength (how much pain they can absorb), and their political-military dependence on the U.S. In simple terms, strategic autonomy in political, economic, and military spheres determines a country’s capacity to respond.

Ultimately, countries like the UK, Japan, and South Korea have effectively abandoned any resistance. For a post-Brexit UK, the relationship with the U.S. is its last thread of global influence—so that PM Starmer viewed a 10% tariff as a relative victory. In Japan, Shigeru Ishiba called the tariffs a “national crisis.” While pleading with the U.S. for exemption, the Japanese government quietly began drafting support measures for businesses and households, including plans for supplementary budgets. In South Korea, where President Yoon Suk Yeol has been removed from office and a new election isn’t scheduled until June, making decisions on tariff policy seems even more unlikely.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba said on April 5 that he plans to speak with Donald Trump “within the next week” to discuss the president’s decision to slap Tokyo with tariffs.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba said on April 5 that he plans to speak with Donald Trump “within the next week” to discuss the president’s decision to slap Tokyo with tariffs.

The wavering stance of these major economies is part of Trump’s winning formula: even if he fails to pressure China, he can still exploit their weakness to recoup the costs of his tariff war. Those who believe Trump is simply reviving 19th-century imperial trade preferences misread his strategy. Any similarities are merely side effects—not the central objective—of his international trade policy.

Currently, only China and the EU remain as possible challengers to Trump (Russia, partially excluded from the neoliberal global trade system, might count as a “half” challenger). The EU, like China and the U.S., has a sufficiently large economy, a somewhat alternative trade settlement currency, and a degree of industrial independence. It also consistently emphasizes strategic autonomy and refuses to see itself as an economic colony of the U.S. From a pure perspective of currency internationalization, the EU even enjoys an advantage over China—the euro is more internationally integrated than the RMB. Moreover, the EU, outside North America, is a core pillar of neoliberal globalization.

However, unlike China’s swift imposition of reciprocal tariffs, the EU’s only responses so far have come from Macron’s largely ignored threats and vague warnings from European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. This just exposes the EU’s lack of genuine strategic autonomy.

As I’ve previously argued, one of the EU’s greatest structural flaws lies in its supranational institutions, which are powerless to prevent member states from prioritizing self-preservation. The dream of a pan-European identity is beautiful, but each country’s real concern is maximizing its own share of the pie.

As a result, EU member states have been unable to reach a consensus on Trump’s tariffs, as each country has its own concerns. On one hand, as the most important second-tier economies within the EU, they are too big to fail. Greece may be allowed to go bankrupt, but a collapse of either Italy or Spain would have devastating consequences for the broader EU economy. On the other hand, these two countries also reflect the stark fiscal realities of Southern Europe, where sovereign debt levels are already alarmingly high. Any comprehensive EU confrontation against Trump’s tariffs would only further limit their already shrinking fiscal room for maneuver. (France faces a similar dilemma, though to a slightly lesser extent.) This is why, despite sitting on opposite ends of the political spectrum, the governments of both countries have called for calm and urged the EU to avoid a full-scale confrontation.

Eastern European countries, by contrast, are more likely to oppose tariff escalation due to their political and military dependence on the United States. Compared to Western Europe, these nations generally run smaller trade surpluses with the U.S.—a consequence of their more modest economic scale—and rely far more heavily on American security guarantees. While many of them are frustrated with Trump’s shifting stance on the Russia-Ukraine war, that dissatisfaction isn’t strong enough to override a basic reality: unless they surrender to Russia, their only viable security partner is the United States. This is a widely accepted truth not only in the Baltic states but also in major Eastern European powers like Poland. As Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk put it, “A severe and unpleasant blow, because it comes from the closest ally, but we will survive it. Our friendship must also survive this test.”

France and Germany are the most vocal resisters—or, more accurately, the only real drivers of pushback. For Germany, already suffering from a severe industrial downturn, Trump’s tariffs delivered a direct blow to the incoming government. The Guardian even described it as “another nail in the coffin” for Germany’s auto industry. Macron, who takes every opportunity to perform France’s commitment to strategic autonomy, was even more proactive. Well before Trump’s tariff hammer came down, France had been pushing for a unified European response. If France and Germany were operating outside the EU framework, they might well have chosen to give up resistance like the UK, Japan, and South Korea. But with the weight of the EU behind them, they clearly have more ambitious ideas.

However, by leveraging the EU to counter U.S. tariffs, France and Germany are effectively offloading part of their own costs onto other member states. If they truly wanted to act independently, they could bypass the EU and impose tariffs on the United States directly. Of course, many readers might point out that the EU holds exclusive authority over external trade policy. But let’s not forget: even policies like the Schengen Agreement—which also fall under EU jurisdiction—can be swiftly suspended when national governments invoke a state of emergency. Put bluntly, if France and Germany decide to break EU rules, what can Brussels realistically do to stop them?

This cost-sharing approach has already sparked strong resentment among other EU member states. Worse still, while pushing for a collective EU response to U.S. tariffs, France and Germany have also sought to shift as much of the economic burden as possible onto other members. For example, France is the EU’s largest wine exporter and much of its wine goes to the U.S. When Trump threatens retaliatory tariff on European wine after EU proposed American whisky tax, the French prime minister last month requested that American bourbon be excluded from the EU’s retaliation list. Similarly, Germany’s incoming government has unveiled a €500 billion stimulus plan aimed at boosting domestic production, prompting accusations from other EU countries that Germany is engaging in unfair competition within the Union.

Clearly, the internal scheming among member states and bureaucracy are the key reason behind the EU’s failure to respond to Trump’s tariffs. This is a long-standing issue for the EU as a supranational body, and Trump’s tariff war has only deepened existing fault lines. After prolonged bargaining, the EU will likely offer some form of response—but its lack of true strategic autonomy makes it highly likely to blink first in this game of chicken. Every time Trump raises the stakes, internal divisions within the EU are further exposed, and the darker side of European integration becomes more apparent. Put more precisely, Trump has numerous ways to circumvent the EU, France, and Germany, targeting and splintering individual member states one by one.

Ursula von der Leyen stated that Brussels has a “strong plan to retaliate” against Trump’s reciprocal tariffs

Ursula von der Leyen stated that Brussels has a “strong plan to retaliate” against Trump’s reciprocal tariffs

As for the once-frequent talk of strategic economic cooperation between China and the EU, one can only say the theory sounds promising, but political reality is far more sobering. It’s become increasingly clear to Chinese observers that, since the COVID-19 pandemic and especially the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, the EU has been losing weight in China’s strategic economic calculus. More importantly, even today, the EU’s mainstream political forces show little genuine willingness to strengthen economic cooperation with China.

In the various signals coming out of the EU, there has been emphasis on strengthening southern market agreements and building a Mediterranean economic zone—but notably little discussion of enhanced China-EU trade cooperation. In fact, this perspective barely exists outside academic circles. On the contrary, one of the hottest topics in the European Parliament right now is Huawei’s bribery scandal, which a significant number of European politicians are using as pretext to intensify strategic competition with China. Not to mention that the Chinese spy case involving Prince Andrew is currently one of the most popular tabloid stories in the UK. The once-celebrated China-EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment was effectively dead on arrival.

When China and the U.S. clash, it’s true that Europe often suffers as collateral damage. But history has shown Europe’s consistent tendency to side with the U.S. under pressure. As more and more economies concede to the U.S. in this tariff war, China will become the last line of resistance against Trump’s trade offensive. This unprecedented pressure will pose a major test to the strategic resolve of both China and the United States. That is why I continue to emphasize the importance of building stronger domestic communities and regional economic circulation.

Trump’s tariff policy signals a profound reordering of the global economic landscape. Only by accelerating internal market integration can countries build resilience against extreme external volatility. The illusion of strategic partnership under neoliberal globalization is over—welcome back to the harsh and painful era of great-power strategic competition.

The post EU’s Weakness Stops It from Confronting Trump to the End first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Tariff War: Trump’s Desperate Move, With One Unexpected Win| Explained by Charles Liu first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Tariff War: Trump’s Desperate Move, With One Unexpected Win| Explained by Charles Liu first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Trump’s F-47 Fighter Dream is Now in China’s Hand first appeared on China Academy.

]]>Among these measures, the one that struck me as most familiar was the “Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs imposing export restrictions on seven medium-heavy rare earth elements—samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium.” The Chinese Commerce Ministry explicitly stated that “these materials have both civilian and military applications, and export restrictions are a standard international practice.”

In this piece, let’s talk about how China’s latest rare earth export restrictions will hit the U.S. military.

The rare earth family consists of 17 elements – 15 lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium, which typically coexist with and have similar applications to the lanthanides. Based on atomic weight, they can be divided into light rare earths and medium-heavy rare earths. Light rare earths are relatively more abundant and widely distributed. In contrast, medium-heavy rare earths are far scarcer and unevenly distributed – the vast majority are concentrated in China. These particular elements serve as indispensable resources for national defense, military industries, and advanced technology sectors.

Mountain Pass in California, America’s sole rare earth mine, mainly produces light rare earths

Mountain Pass in California, America’s sole rare earth mine, mainly produces light rare earths

So when people say “China dominates the rare earth market,” what they really mean is China’s overwhelming restrictions over the reserves, mining, and refining capacity of medium-heavy rare earths—the most critical and scarce category. According to U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) data, nearly 100% of America’s medium-heavy rare earth imports in recent years have come from China.

This exposes the fatal flaw in Western media claims that the U.S. can simply “find rare earths elsewhere” to break free from Chinese dependence. Whether it’s Australia or Ukraine, their so-called “rare earth resources” are overwhelmingly light rare earths—not the heavy, defense-critical ones China monopolizes.

So just how impactful will China’s latest export restrictions on medium-heavy rare earth materials be? Let’s take one example from China’s restrictions list: samarium-cobalt magnets.

Back in 2022, U.S. media overhyped when reports revealed that F135 engines—the power plant for Lockheed Martin’s F-35 stealth fighters—contained a “prohibited” Chinese-made component. The Pentagon even halted F-35 deliveries during its investigation. Detailed investigation reports show that samarium-cobalt magnets from a Chinese supplier were used in the engine’s lubrication pumps.

The Wall Street Journal’s then coverage on this matter

The Wall Street Journal’s then coverage on this matter

Samarium-cobalt magnets are composed of cobalt, samarium, and other metallic materials. They exhibit exceptional magnetic properties (high remanence, high coercivity, and high maximum energy product), outstanding temperature stability, superior oxidation resistance, and corrosion resistance. These magnets are widely used in aerospace, defense/military systems, microwave devices, telecommunications, medical equipment, automotive systems, magnetic pumps, precision instruments, various sensors, and high-performance motors.

Different shapes of Samarium-cobalt magnets

Different shapes of Samarium-cobalt magnets

Interestingly, despite facing widespread criticism from U.S. media, the Pentagon suddenly announced a “waiver” for Chinese-made samarium-cobalt magnets just one month later – explicitly allowing F-35s to continue using these Chinese rare earth products. This directly demonstrates America’s inability to find substitutes for these specialized Chinese components.

The reality is unavoidable: China dominates global production capacity for these samarium-cobalt magnets, whose exceptional heat resistance makes them irreplaceable for critical F-135 engine components like sensors and control systems.

An F135 engine prepared for installation on an F-35 fighter

An F135 engine prepared for installation on an F-35 fighter

In fact, samarium-cobalt magnets have applications far beyond just the lubrication pumps of F-35 fighter engines. They are also used in missile and aircraft gyroscopes and accelerometers, ensuring stability under extreme temperatures (such as during high-speed flight or high-altitude conditions) to maintain navigation accuracy. Additionally, they can be employed in sonar systems to improve the efficiency of sonar transducers and enhance underwater detection capabilities.

This example reveals that U.S. advanced weapons systems rely on medium-heavy rare earth elements far more than publicly acknowledged. America’s cutting-edge fighter jets and next-generation Aegis combat systems extensively use gadolinium, terbium, yttrium and dysprosium in their active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars. For instance, the AN/APG-81 radar equipped on F-35 fighters employs terbium-doped neodymium magnets – which are specifically included in China’s new export restrictions list.

The AN/APG-81 radar of the U.S. Air Force

The AN/APG-81 radar of the U.S. Air Force

On March 21st, Trump just announced the U.S. Air Force’s sixth-generation fighter program, officially designated it as the F-47 and assigned Boeing the contract. Notably, this aircraft’s stealth coating requires gadolinium, while its advanced engine blades incorporate yttrium to enhance heat resistance – both of the elements are included in China’s export restrictions list.

Thus it’s fair to say that before the U.S. Air Force’s much-touted sixth-generation F-47 fighter even completes its maiden flight, China has already severed its supply chain for critical materials. The F-47’s predicament merely epitomizes the broader challenge facing advanced U.S. weapon systems under China’s export restrictions – after years of suppressing China’s legitimate technological development (like drones) under the pretext of “military potential,” the Pentagon is now getting a taste of its own boomerang tactics.

The post Trump’s F-47 Fighter Dream is Now in China’s Hand first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Trump’s True Demands from China first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The China Academy: It’s very interesting. The U.S. and China are on very different trajectories. China is taking a firm stance, saying, “We need to open up.” On the other hand, the U.S. is focusing on contraction.

Louis-Vincent Gave:Yes, and Trump has been very focused on building “Fortress America,” etc. Having said all this, I think if you’re China, your big fear when Trump was elected was very different.

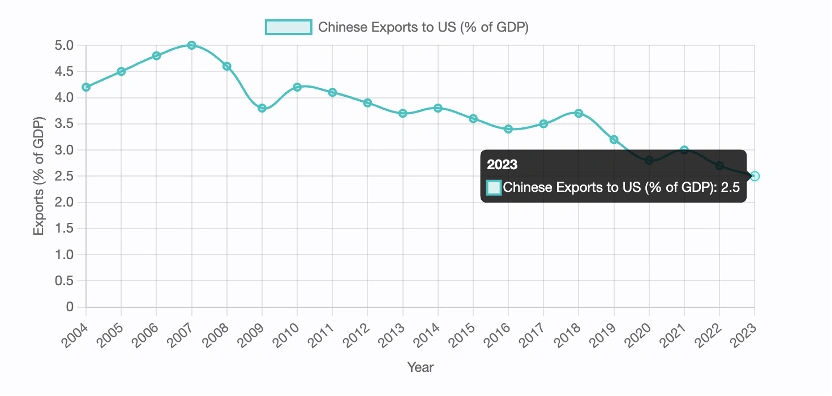

Three months ago, the big fear wasn’t that Trump would slap a bunch of tariffs on Chinese goods. To be perfectly blunt, China doesn’t really care about that anymore. If you go back a decade, Chinese exports to the U.S. made up 8% of China’s GDP. Now, it’s only 2.7% of GDP. So, it doesn’t matter as much as it used to.

I think the real fear for China was that Trump might try to build an anti-China coalition. That he would go to Europe, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Australia, Canada, Mexico, and say, “Hey, you can’t do business with China anymore. You can’t let them build factories here. You can’t trade goods with them. You’ve got to block out China. I’m blocking China, and you have to do it too.”

Well. But fast forward to today, and now if Trump goes to Europe and says, “Hey, if you don’t block out China, we’re not going to be friends,” Europe might reply, “We’re already not friends. What are you talking about? You can’t tell us what to do.”

So, in that respect, you might say Trump’s policies are bad news for China and could crush confidence, etc. But if I’m Xi Jinping or Li Qiang, I might think Trump is actually good for China. Why? Because he wants to close America off from the world. Perfect! That allows China to do more business with Indonesia, Thailand, and other countries.

Today, if you’re Thailand or Indonesia and you see how Trump treats countries like Ukraine, Canada, and France—countries that are nominally friends of the U.S.—you might start thinking, “The U.S. is not a very stable friend. Should I turn my back on China and do more with the U.S., or should I strengthen ties with China?”

I need to do more with China and less with the U.S., right? That’s probably what they’re thinking. And that’s what matters more to China right now. Can China grow its business with Indonesia? Can it grow its business with Saudi Arabia? With Brazil? These are the big questions. And today, I think that’s much more likely than it was a few months ago.

It’s China’s chance right now. I think it is, especially when it comes to Southeast Asia. Where the U.S. closing in on itself opens up huge opportunities for China. What China should do now is pursue friendly diplomacy.

China could say, “Look, we just want to be friends. Let’s do more business together. We’re not here to bully you. Sure, we could bully you because we all know the U.S. isn’t going to protect you, but that’s not who we are. We’re here to do business. Let’s be friends and achieve mutual benefits.” This is a huge opportunity for China.

Q8

The China Academy: The expectations of a U.S. economic recession are growing. The stock market has experienced some turbulence over the last week and last month, and U.S. Treasury bonds are also on shaky ground. Can Trump alleviate the crisis in the U.S.? And what impact will the instability of the U.S. economy have on the global economy?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I think this time around, Trump is very different from the first time he was president. Back then, Trump was always tweeting about the stock market and constantly talking about it. This time, however, Trump has a much bigger challenge on his hands.

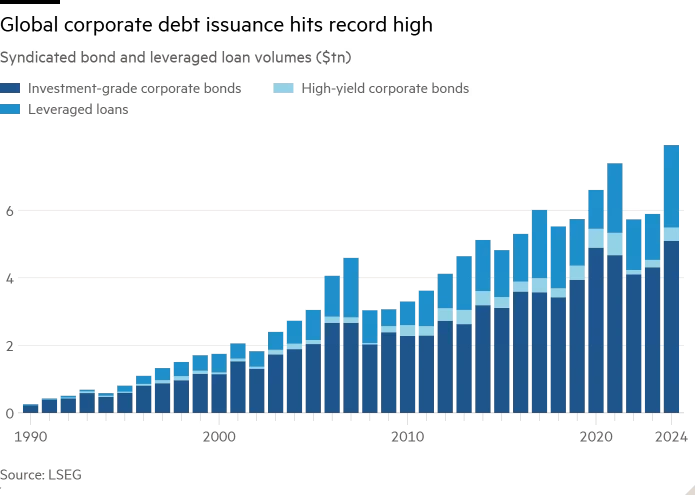

Few people realize this—or even remember—but five years ago, when COVID hit (pretty much exactly five years ago), U.S. corporations went out and borrowed a lot of money. Interest rates were at zero, so they issued record amounts of debt—tons and tons of corporate debt. Now, most corporate debt in the U.S. is structured with a five-year term. That means these corporations have to roll over their debt in the second half of this year and the first half of next year.

This is a big problem for Trump, because as these corporations roll over their debt at much higher interest rates, they’re going to stop capital spending. They’ll start firing people, reducing expenses, and this could very well push the U.S. into a recession at precisely the wrong time—right before the midterm elections.

And the last thing Trump wants is for Democrats to win during the midterms. If they win, they’ll push for impeachment and other political battles, leaving Trump with two years just fighting the Democrats.

So if you’re Trump, your main goal today is to get interest rates down. Otherwise, corporations won’t be able to roll over their debts. He’s doing everything he can to achieve that—reducing government spending, pressuring foreign governments to buy long-dated U.S. bonds, and talking down economic growth.

The current U.S. policy is therefore aimed at lowering bond yields. And if you get lower bond yields, you also get a weaker U.S. dollar.

Now, the third part of Trump’s policy is to get lower energy prices. That’s why he was so willing to throw Ukraine under the bus. Essentially, he wants Russia to start producing more oil. Before the Ukraine war, Russia was producing roughly 10.5 million barrels of oil per day. Now, it’s producing only 9 million barrels per day.

For Russia to ramp up production, they’ll need companies like Halliburton, Schlumberger, and other Western oil service firms to upgrade their equipment. Trump’s policy is therefore very simple: lower interest rates, lower the dollar, and lower oil prices.

It doesn’t mean he’ll succeed, but those are his three main goals.

If he’s successful in these goals, it’s great news for many markets. For example, if you’re China, how great would it be to have lower interest rates, a weaker dollar, and lower oil prices? It would create a boom.

If you’re the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), you’d be able to keep your interest rates low, and everything would run smoothly.

In summary, I think the odds are pretty high that these are the policies the U.S. will pursue: lower interest rates, a weaker dollar, and lower oil prices. If that’s the case, there’ll suddenly be more exciting opportunities in global markets than just buying U.S. equities.

Q9

The China Academy: But if Trump wants to decrease the interest rate, will he give up the tariffs? Because tariffs could worsen inflation.

Louis-Vincent Gave:You’re right—the tariffs do seem contradictory to that goal.

So here’s the big question: are the tariffs a goal in themselves, or are they just a tool to achieve something else? I still think that, for Trump, tariffs are a tool to achieve something else.

What he wants is to sit down with Xi Jinping in June and say, “Look, either I’m going to impose a bunch of tariffs, or you’ve got to buy a lot of my bonds. I’m going to issue some 50-year zero-coupon bonds, and you’re going to buy those.”

And he’s going to say the same thing to the Europeans, the Japanese, and the Koreans: “You guys have big trade surpluses with the U.S. So either I’ll impose tariffs to reduce the trade surplus, or you take that surplus and invest it in my 50-year zero-coupon bonds.”

I think tariffs are really just a tool to get foreign governments to fund the U.S. deficit. When you listen to Trump’s rhetoric, it always comes back to the same theme: “The foreigners will pay.”

For example:

“The Mexicans will pay for the wall.”

“The budget deficit? We’ll sell U.S. citizenship for $5 million each.”

“The tariffs will pay for themselves.”

It’s always about foreigners footing the bill.

So I still believe that tariffs are a tool—not the end goal in themselves.

Q10

The China Academy: The Chinese market hasn’t reacted significantly to Trump’s tariffs, why is that?

Louis-Vincent Gave:You’re right. Judging from the market’s reaction, it doesn’t seem to matter much for China.

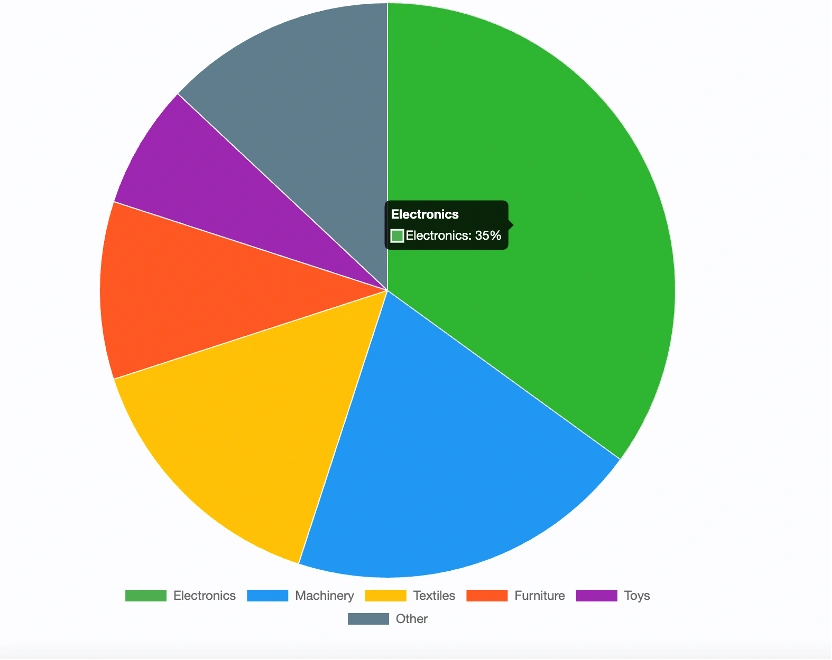

To be perfectly honest, if you look at what China exports to the United States, roughly speaking—and I’m rounding the numbers—it breaks down like this:

About 20% of exports are tied to Apple. If the U.S. wants to put a bunch of tariffs on Apple products, so be it. Who cares?

Another 20% is high-end electronics. These supply chains are incredibly complex and can’t easily move to places like Vietnam or India.

Then there’s another 20% that’s machine tools—both high-end and low-end. This includes things like Black & Decker products or Johnson Motors. Conceptually, this part could move elsewhere, but it’s not happening quickly.

Finally, the remaining 40% is the low-value-added stuff: shoes, T-shirts, Tupperware, furniture, plastic toys, etc. This part is already gradually leaving China, moving to countries like Vietnam and Indonesia.

The Chinese leadership doesn’t seem to care much about losing that last 40%. They know it’s leaving anyway. Low-value-added industries like shoes and toys are bound to relocate over time.

So, when you put this all together, exports to the U.S. account for only 2.7% of China’s GDP. That’s why the Chinese market doesn’t really care about the tariffs.

In fact, the market has already priced in the deterioration of U.S.-China relations, which started back in 2018. The fact that relations are bad is no longer news—it’s already baked into the market.

What’s not priced in, however, is the possibility of relations improving.

Now, if Xi Jinping and Trump meet in June for their rumored “joint birthday summit”—because Xi’s birthday is June 15 and Trump’s is June 14—and if they get along and sign some kind of deal, that would be a huge catalyst for the markets.

If that happens, it’ll be a big celebration—not just for their birthdays, but for the markets too.

Q11

The China Academy: This is definitely something to look forward to. From an investment perspective, what are the key geopolitical risks to watch this year? Particularly in light of Trump’s strategy of retrenchment, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future trajectory of U.S.-China relations?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I tend to have an optimistic outlook most of the time.

That said, I also believe people worry too much about geopolitics affecting markets. Yes, bad geopolitical headlines can have an impact, and to be fair, the deterioration of U.S.-China relations over the past 5–6 years has had a significant effect. So I don’t want to completely dismiss those concerns. There is an element of risk there.

Now, looking ahead, Xi Jinping and Trump are most likely going to meet in June. Here’s what I think will happen between now and then: In April and May, Trump will ramp up his rhetoric against China. On April 1st, the Commerce Department, Treasury Department, and USTR are set to release their recommendations for tariffs.

During this time, Trump will repeatedly threaten China with a slew of tariffs and will publicly “beat up on China.” This is classic “Art of the Deal” strategy: you beat up your opponent first, and then sit down to negotiate. Once the other side feels pressured, you extract concessions from them.

If you’re Xi Jinping, you’re not going to respond during April and May. You’ll let Trump do all the talking while you keep a low profile. Then, in June, you sit down with Trump, strike a deal, and everyone walks away feeling satisfied. This sets the stage for a strong second half of the year.

To me, that seems like the most likely scenario.

Q12

The China Academy: What Is the Biggest Geopolitical Risk for Investors This Year?

Louis-Vincent Gave:I think the biggest risk to this plan would be a sudden spike in oil prices.

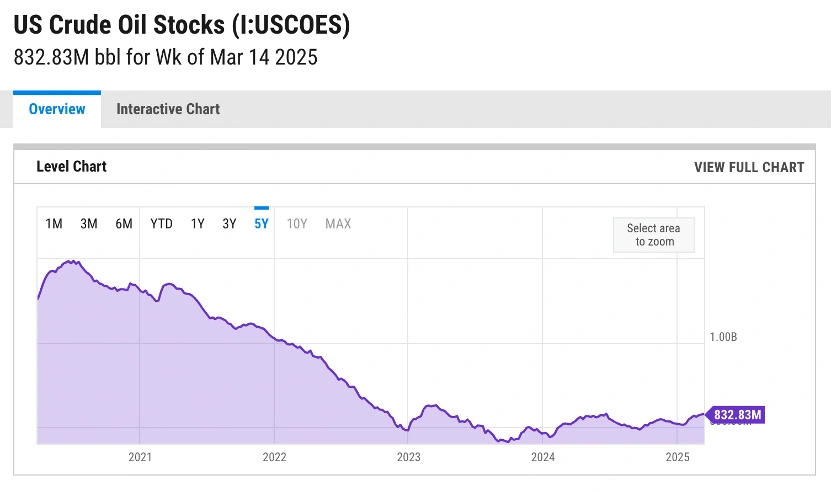

We’ve grown accustomed to a world of relatively cheap oil in recent years. However, global oil inventories have been significantly drawn down:

U.S. oil inventories are near 20-year lows. China, which usually holds high oil inventories, is currently running low. The same is true for Japan.

Now, I’m not saying oil prices are going to surge, but let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario. For example, suppose Trump decides to bomb the Houthis in Yemen. In retaliation, the Houthis could turn around and target Saudi Arabia’s refining facilities as payback, reasoning, “We can’t attack the U.S. directly, but we can hit Saudi Arabia, their ally.”

Again, I’m not saying this will happen, but if it did, oil prices could quickly jump to $100, $110, or even $120 per barrel.

In such a scenario, the Federal Reserve would likely raise interest rates to combat inflation, and markets would sell off sharply.

While I don’t think this is a likely outcome, you asked about risks, and for me, this is the one I worry about most. A sudden surge in oil prices could throw everything off balance.

The post Trump’s True Demands from China first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Can Trump Make China Save U.S. Bonds? first appeared on China Academy.

]]>The post Can Trump Make China Save U.S. Bonds? first appeared on China Academy.

]]>