How Africa is Drained by the West through Hospitals

Since the first Chinese medical team was dispatched to Algeria in 1963, Chinese medical teams have traveled thousands of miles to save countless lives in the past 60 years. For a long time, when it comes to the topic, the media and intellectuals have focused more on macro-level agendas such as humanitarian aid, international cooperation, or health diplomacy. There has been little discussion on the micro-level practices of medical teams in Africa. The actual conditions of Chinese medical teams within the local medical ecosystem of Africa have rarely been deeply investigated.

Between 2015 and 2019, we conducted anthropological field research in East Africa. During this period, we met many members of Chinese medical teams in Africa and conducted interviews with them. After returning to China, we also conducted interviews with officials from the former National Health and Family Planning Commission (now the National Health Commission, NHC), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Chinese CDC) responsible for dispatching medical teams to Africa. As a result, we gained a comprehensive understanding of the current situation of Chinese medical teams in Africa. This article is based on the field research data collected in Uganda, Malawi, Mainland Tanzania, and the islands of Zanzibar, revealing the real problems and challenges faced by Chinese medical teams within the local medical ecosystem of Africa.

I.Phase Differentiation of Africa’s Medical Ecosystem and the Discrepancy in Chinese Medical Teams to Africa

As part of China’s foreign aid, from 1963 to 2023, China dispatched a total of 24,000 personnel in medical teams to Africa. Currently, 45 medical teams are working in 100 sites across 44 African countries. In this process, the members of Chinese medical teams have established cooperative relationships with African hospitals through clinical teaching, surgical demonstrations, academic exchanges and lectures, remote guidance, and mobile medical services. They have supported the establishment of specialized health centers, trained medical personnel, improved the well-being of the people in recipient countries, and enhanced the medical technology level of those countries. Through all these selfless humanitarian practices, Chinese medical teams have gained the high trust of recipient governments and people.

The medical teams deserve such praise. However, compared to the current generations, their predecessors may be more qualified for these praises. During the author’s research in several East African countries, it was revealed that these countries require medical practitioners to obtain a professional license issued by their national medical association to practice medicine. This has resulted in many members of Chinese medical teams struggling to obtain licenses due to language barriers. They can only hold volunteer certificates and engage only in auxiliary support. Some doctors complained, “Previous members like Dr. Liu Fangyi were treated as state guests, while we are just volunteers without a license, prescription rights, or medicine supply. We are merely doctors in name.” The “previous members” refer to the Chinese members during the time of Julius Nyerere, the 1st President of Tanzania.

At that time, Tanzania had just gained independence and embarked on the path of African socialism, attempting to develop primary healthcare and rural medical services. China sent medical teams to train Tanzanian healthcare personnel for this goal, leaving “a medical team that never leaves” for the local people. At that time, Tanzania did not have the requirement for foreign medical teams to possess such licenses. The medical teams relied on their medical skills and experience to make breakthroughs and became “honored guests” in Tanzania. However, due to the mandatory regulations on professional qualifications now, except for a few medical team members who can quickly participate in clinical diagnosis and treatment in departments as doctors, most doctors usually need about a year and a half to obtain the work permit, residence permit, and the professional license. For the medical team members with only a two-year or one-year period of dispatch, they’ve been left with limited time to perform their professional practice.

The differing treatment in the two periods is not because the previous members had higher medical skills than their successors, nor is it due to a change in government leading to a diplomatic shift. It is because they were embedded in different stages of Africa’s medical ecosystem.

The first stage is the era of missionary medicine. Missionary medicine viewed the assistance to African patients as religious redemption, using it as a means of “civilization and enlightenment” and “spreading the gospel.” With the help of medical services, missionary medicine paved the way for preaching and became the spearhead of the colonialist force.

The second stage is the colonial medicine stage which began in the late 18th century, or the imperial medicine stage. Western medicine operated in their conquered colonies, serving the establishment and maintenance of colonial regimes. Military doctors serving the armed forces, civil doctors serving colonial governments, missionaries serving for preaching, and medical researchers studying tropical diseases all made appearances. The Western colonial medical system trained the first generation of local medical elites in Africa, but their primary focus was still serving European powers and their local agents.

The third stage is the post-colonial medicine stage that accompanied African independence movements after World War II. The medical field of the newly independent African countries remained intricately linked to colonial medicine. This was mainly manifested in the enthusiasm of local medical elites for elite medicine, the continuation of missionary medical practices, medical aid from former colonial powers or other Western countries, and the establishment of various branches by Western medical schools or research institutions. Although Africa faced various constraints in the medical field, political independence allowed African governments to have weity to formulate health system policies and choose their path of health development. During this stage, most African countries attempted to develop healthcare, either through socialist practices, focusing on primary healthcare and rural medical services, or by embracing capitalist medicine, introducing private capital, and developing private healthcare.

The fourth stage is the democratic political medicine stage. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, African countries faced financial difficulties caused by economic crises and had to undergo structural adjustments as required by the World Bank and the West. Most African countries transferred to democratic politics. In this stage, Africa’s medical ecosystem was characterized by a balance between democratic politics and the healthcare system. More specifically, the balance is achieved through the interaction of three values: Utilitarianism, humanitarianism, and neoliberalism. Utilitarianism focuses on “basic coverage” and aims to serve the majority with limited resources, prioritizing primary healthcare. Humanitarianism centers around the “universal right to healthcare”, advocating for the public nature of the healthcare system and resisting market-oriented tendencies, thus leading to demands for free healthcare services. Neoliberalism, on the other hand, perceives healthcare services as commodities and advocates for the transformation of the healthcare system through privatization and marketization. It promotes strict professional standards for physicians, establishes high standards for drug and medical device access, and pursues advanced medical technology and talent. The interaction of these three values has led to the uncertainty of Africa’s medical ecosystem. However, with the privatization process in the healthcare field, most African countries have turned to neoliberal healthcare systems.

The first generation of Chinese medical teams was meeting the post-colonial medicine stage of Africa’s medical ecosystem. The continent was in the peak period of the independence movement back to the time. Due to long-term colonial rule, the newly independent countries faced financial constraints and had severely underdeveloped healthcare systems, requiring external support. In the spirit of humanitarianism, the Chinese government based on the needs and proposals of African countries, dispatched medical experts to Africa. The Chinese experts provided guidance and training to local staff, participated in local medical practices, provided medicines and equipment supplies, and constructed of medical infrastructure. This act of providing timely assistance did not have many structural restrictions, allowing Chinese doctors to immediately engage in medical services.

However, today, the Chinese medical teams today are facing an African medical ecosystem dominated by neoliberalism. African countries have introduced Western standards for medical practice, requiring years of training and passing the licensing examination to be able to practice medicine legally. Although the Chinese members have already obtained their licenses in China and are experienced professionals, they are unable to practice as “regular doctors” in these countries during their dispatch, and may even encounter investigations from immigration officials.

II. The Dominance of Neoliberalism and the Awkward Situation of Chinese Medical Teams

The doctor’s license mentioned earlier is just the tip of the iceberg in the neoliberal medical ecosystem. Neoliberalism believes that the healthcare sector should follow market logic since any non-market-competition monopoly leads to inefficiency. Under the transformation of neoliberalism, the healthcare industry in Africa has been significantly privatized in recent decades. Due to the lack of pharmaceutical production capacity and market competition, modern medicine in Africa is heavily reliant on imports, resulting in high prices. Many African countries allow doctors in public hospitals to work in more than one hospital, and allow them to open pharmacies, clinics, or even private hospitals, to help address the shortage of national healthcare resources. However, under the influence of neoliberalism, some doctors bring hospital drug supply back to their private pharmacies for sale through fraudulent prescriptions, generating substantial profits. Within public hospitals, there is a prevailing trend of doctors pursuing self-interest and exceeding welfare benefits. This not only leads to frequent medical strikes demanding salary increases but also causes a large number of healthcare and public health workers to flock to higher-paying positions in the private sector.

The pursuit of advanced technology and talent is the essence of neoliberalism. Although Africa lags in overall medical levels, its professional standards and pharmaceutical quality standards are comparable to those of the World Health Organization and Western countries. A former staff member of China’s National Health Commission, responsible for dispatching medical teams to Africa, expressed concerns about this development strategy that surpasses the economic development level of African countries:

Many healthcare officials in Africa are trained in Western countries and have excellent backgrounds, but they lack a clear development strategy. Perhaps there is one, that mimics American standards and then lets the market drive the process. The most important aspect of our aid to Africa is sharing our experiences in health development. 60 years ago, many of the health indicators of China were similar to those of Africa. Why has China significantly improved its health indicators while African countries have not made significant progress? To a large extent, they have not found a suitable path for themselves. If China was on the path that Africa is undergoing, spending several years in training to obtain a medical license, we would not have had those “barefoot doctors”. Without the “barefoot doctors,” it would have been impossible for China to train rural healthcare workers in a short period and help farmers address their basic healthcare needs. The “barefoot doctors” were a feasible path that China explored. Starting from the “barefoot doctors,” we gradually transitioned to the path of so-called standardized doctors and professional doctors. African countries did not do this. Instead, they immediately demanded their healthcare professionals meet the professional standards of Western countries. Who can achieve that overnight? Even if they could, who would stay and work there when they could be paid better in America, the United Kingdom, or France? We must consider the reality and not assume that setting so-called lower standards for licenses would result in a lower level of well-being for African people. On the contrary, adhering to high standards prevents the majority of Africans from accessing basic medical care. Many people have criticized China’s pharmaceutical standards for being lower than those of Western countries and the World Health Organization. However, if we set such high pharmaceutical standards, many people would either have no access to medicine or would have to spend more money to purchase imported drugs from the West. Although it may seem like a painful choice, it is a realistic one. We keep in mind our situations and gradually improve these standards, which has led us to where we are now. African countries, on the other hand, immediately adopt Western standards, demanding high pharmaceutical standards and strict professional standards, which may look good, but what will they achieve? It is just a fancy blueprint at the end.

Africa lacks pharmaceutical factories and suffers from a lack of medicines. However, the African countries insist on setting the same pharmaceutical standards as those of Europe, America, and the World Health Organization. This means that even the simplest medicines need to be imported from the West. The impoverished African society ends up consuming expensive drugs from developed countries, which not only deprives the general public of basic medical needs but also leads to significant resource waste. Officials from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs have expressed their frustration on the situation:

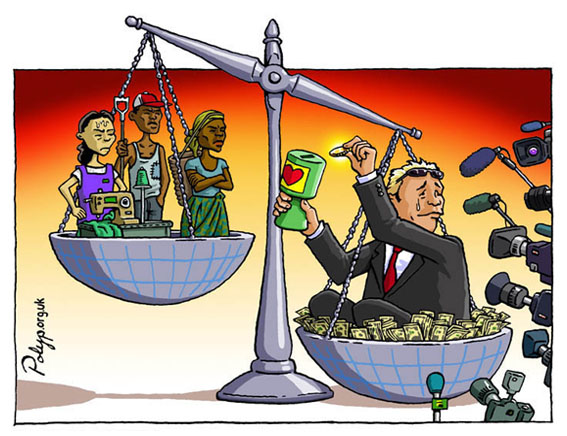

We should not merely sustain a deficient Africa, but instead help it develop its capabilities. The West has set high barriers for medical products, and many of our domestically made drugs cannot enter the African markets that follow their standards. If our domestic drugs can meet the needs of the Chinese people, why can’t the same drugs help African people? We should develop affordable medicines that people can access. We welcome the Western countries to set up pharmacies in Africa. And if you don’t produce, you shouldn’t stop us from producing. No one should waste so much money to buy drugs and only make those people in developed countries richer. Let’s take the metaphor of fishery. The West is giving fish, but we are not only to teach you how to fish but also to empower you to fish by yourself. We aim to strengthen their pharmaceutical production capacity. We approach this issue with an open attitude and are willing to cooperate with the West. Together, we should establish a shared community and expand the African medical market instead of blockading each other. This is not beneficial for either side and does not serve the medical needs of Africa.

With the development of Africa’s economy, its healthcare sector has also made progress. Some African countries, shifting their attitudes toward the healthcare sector, now ask for advanced equipment and technology from Chinese medical teams, or more specialized health centers, rather than just sending individual “Chinese experts” to work alone. The recent Ebola epidemic made African countries realize the importance of establishing disease control laboratories and requested China for such help. After the Ebola epidemic, in addition to personnel dispatch, China sent advanced technology to Africa and helped set up mobile and fixed P3 laboratories within merely three months. Of course, the work was not done when they finished constructing a lab facility. Personnel training, biosafety issues, and legal regulations, all of these were taken into consideration to strengthen biological security. Any subtle but improper handling may lead to virus leaks. While learning, training, and enhancing disease prevention and control capabilities are the correct course, the whole framework requires mutual coordination between countries, and there are challenges in coordinating among African Union member states.

Considering that national hospitals, private hospitals, and specialized medical centers in major African cities can generally meet the needs of those urban areas, some African countries have requested the Chinese medical teams to practice medicine not in urban facilities but the remote areas with limited resources and fewer doctors. The dispatch itself is not a relaxing journey, the team members are fully aware of that and prepared for challenging environments. Encouragingly, compared to before, the overall living conditions of the medical teams in Africa have improved. In the author’s research in Uganda, Malawi, Tanganyika, and the islands of Zanzibar, only one medical team has no settled residence, with members living separately and having to take care of their food, residence, and transportation. However, in the other places we visited, medical teams there have fixed residences, relative safety, and comfort, and are equipped with chefs, drivers, and interpreters. They can adapt to the living environment quickly after a two-week handover period with the previous medical team. While urban areas have abundant healthcare resources, It’s reasonable to dispatch medical teams to remote areas to save lives and provide assistance. However, in the context of prevailing neoliberalism and overall underdeveloped primary healthcare and public health systems, sending a limited number of medical personnel to remote areas is only a drop in the bucket for the local people.

The guarantee of people’s freedom to choose medical services is the core of neoliberal values. However African people lack sufficient freedom of choice due to poverty. When Western countries and local elites in Africa advocate for the freedom of medical choice, they might ignore the reality of the developing countries and take “civilization” for granted. Regarding the guarantee of freedom of medical choice, African countries have made two outstanding efforts: developing private healthcare institutions and encouraging medical tourism.

Unlike the mismanagement in public hospitals, private medical institutions not only possess top-notch medical equipment and services but also attract top-tier African doctors with higher salaries. Across the continent, the best medical institutions are often private ones. However, these private hospitals are often controlled by foreign capital, such as the Aga Khan Hospital and its network of hospitals spread across East Africa, and the Indian Apollo Hospitals in multiple African countries. Private hospitals naturally perceive their services as commodities, with expensive pricing mainly targeting local affluent individuals and foreigners, ensuring their freedom of medical choice. This becomes a concrete manifestation of neoliberal healthcare.

Medical tourism further intensified neoliberal healthcare in Africa. There is a proverb in Africa that says, “If the husband does not come home for dinner, the wife cannot improve her cooking skills.” Medical tourism is a true reflection. In Africa, health inequality is structural. African elites either choose the best local private hospitals or go directly abroad for medical treatment, especially in Western countries, India, and South Africa. As a result, African governments have to spend a large amount of foreign exchange annually to provide state-funded medical treatment to social and political elites. One consequence of this is the lack of trust in domestic public hospitals, making it difficult for them to receive significant government budgets and resources. Since the general population in Africa primarily relies on public hospitals, medical tourism exacerbates the lag in the development of public hospitals.

The neoliberal-dominated healthcare system favors private hospitals and medical tourism, ensuring the freedom of choice for African elites. However, it leads to the lagging development and mismanagement of public hospitals, and inadequate construction of primary healthcare and public health systems that should benefit the general population. The situation also puts Chinese medical teams in an awkward position. It stems from the imbalance between the perception and the reality. The Chinese medical teams position themselves as “helpers” and “assistants,” expecting to work together with African professionals to improve the well-being of the local population. However, the healthcare system in Africa is dominated by neoliberalism: doctors driven by profit, limited access to essential medicines for the entire population, and officials seeking medical treatment in other countries. This disconnect between perception and reality often puts Chinese medical teams in a value crisis and forces them to redefine their roles.

III. The Awakening of African Healthcare Independence and Opportunities for Chinese Medical Teams

Healthcare independence has always been a part of Africa’s quest along with its independence movement. During the Cold War, although relied on external aid due to economic backwardness, most African countries were exploring paths for healthcare development that suited their situations. For example, Tanzania implemented free healthcare policies and primary healthcare initiatives during its Ujamaa socialist movement; Kenya introduced external capital to promote medical privatization reforms; Many African countries, including South Africa, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Uganda, witnessed a revival of traditional medicine. Recently, benefiting from abundant natural resources, a plentiful workforce, and significant market potential, Africa’s economic development has surpassed the global average growth rate. Benefiting from the growth, Africa has been able to construct hospitals and pharmaceutical factories, train local professionals, enhance disease prevention and control, treat malnutrition in children, and guarantee a certain level of healthcare resources and capabilities. All these achievements have enhanced their vision of healthcare independence. Their efforts towards healthcare independence are mainly reflected in areas including development strategies, disease control, multilateral cooperation, and the promotion of traditional medicine. However, their healthcare development strategies are not well-defined.

One staff member from the Chinese Chinese CDC recounted his visit to the African CDC that left him smiling bitterly:

When we went there, they handed us a project proposal. A pile of paper. Dozens of pages filled with marvelous plans. I read through it, compared it to the reality in Africa, and realized that it was so delusional that we didn’t even know how to implement it. Only after they told us the proposal was written by the US CDC.

The vague healthcare development strategy and the lack of a concrete and feasible goal hinder Africa’s self-development and pose challenges for medical aid efforts. Aid from Europe and the United States has, to some extent, contributed to the ambiguity of Africa’s development strategy. The West often assists in terms of medications, vaccines, disease treatment, and epidemic control but rarely addresses the healthcare system itself. This has led Africa into a cycle of dependency, relying excessively on medical resources from the West, resulting in a lack of motive for a self-sustaining healthcare system.

Nevertheless, the awakening of healthcare independence in Africa clears the direction for Chinese medical teams to Africa. The primary responsibility of Chinese medical aid teams is to “teach people how to fish” by assisting in formulating practical and feasible strategies that can benefit the general population. Due to factors such as climate, mosquitoes, zoonotic diseases, poor sanitation conditions, and risky behaviors, infectious diseases ravage the African continent, including diseases such as HIV/AIDS, Rift Valley fever, Ebola, avian influenza, malaria, and cholera. Especially after the Ebola epidemic, many African countries recognized the importance of conducting disease prevention and control. In 2017, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) was established as the leading institution for the continent’s public health system, with five regional cooperation centers set up in Africa. China has been deeply involved in the entire process from assisting in controlling the Ebola epidemic to constructing the headquarters of the Africa CDC. According to former officials from the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC), China’s assistance to the West African countries in combating the Ebola epidemic marked a turning point for medical aid in Africa. Previously, medical teams focused more on clinical treatment and had limited involvement in the field of public healthcare. The dispatch of Ebola aid teams, training over 12,000 people in total, opened up new opportunities for international cooperation for the Chinese CDC. This progress also highlights the potential of Chinese medical teams in the field of public health management.

In 2014, the Chinese medical teams made new progress in cooperation in preventing the Ebola epidemic in Africa. Previous medical aid to Africa was mainly bilateral cooperation between China and the recipient country, but the effort of Ebola prevention marked the first multilateral cooperation in Africa. The former staff member of the NHFPC recounted that:

Previously, our cooperation with Africa was mostly done by ourselves, with little involvement from other countries. But this time, we participated in UN actions and dispatched experts to the WHO groups, working together with experts from the US and the UK to conduct experiments and discuss the response strategies. We tended to work alone before. In addition, non-governmental organizations and many Chinese enterprises also got involved. African countries welcomed this multilateral cooperation as it maximized the effectiveness of assistance. We were familiar with bilateral cooperation but not much with multilateral cooperation, we thought it was inefficient. However, multilateral cooperation has its advantages. Coordination may be slower, but it sets up rules from a global perspective. For example, once the WHO certifies a drug, most African countries adopt it unconditionally, making things easier without repeating the same registration process in individual countries.

As Chinese medical aid to Africa enters a new stage, the possibility of shifting from bilateral cooperation to multilateral cooperation is increasing. In the future, Chinese medical teams to Africa will not only interact with institutions and people in recipient countries, but also collaborate with international organizations, local NGOs, and medical teams from other countries.

The healthcare independence in Africa is also reflected in the field of traditional medicine. Traditional medicine is deeply rooted in African culture. It emphasizes comprehensive treatment and strong accessibility, playing a positive role in addressing diseases such as HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and chronic illnesses. It has become an important option for African people to seek healthcare independently. China, as a country that values traditional medicine, has always included traditional medicine as part of its medical aid. For example, acupuncture is regarded as the “magic needle of China” in Africa, and acupuncture departments have been established in hospitals in Zanzibar and Uganda. Furthermore, the emphasis on traditional medicine has also fostered relative cooperation between African countries and China. Six countries, including Malawi, Tanzania, Comoros, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Morocco, have signed memorandums on cooperation in the field of traditional medicine with China, covering areas such as laws and regulations, healthcare, education and training, R&D, and industry cooperation. This means that upholding medical pluralism and promoting the exchange of traditional medicine will remain part of the work of Chinese medical teams to Africa.

Conclusion

Sending medical teams to African countries is one of China’s longest-running, most effective, and most down-to-earth foreign aid projects. Initially, the dispatch of medical teams was more of a declaration of international humanitarianism and diplomatic friendship. With the deepening of China-Africa relationships, the dispatch of medical teams has become part of the China-Africa community of common destiny. It is essential to provide precise services to this community of common destiny and analyze the medical ecosystem in Africa. After all, despite restricting the practices of Chinese medical teams, the medical ecosystem in Africa serves as a platform for performing medical expertise and participating in public health governance.

With political democratization reforms, the medical ecosystem in Africa has shifted to medical neoliberalism. Under the dominance of neoliberalism, the medical ecosystem in Africa exhibits unique characteristics in terms of doctors’ practice patterns, drug and equipment standards, and primary healthcare. On the one hand, it guarantees doctors’ professional freedom and promotes the development of private hospitals and medical tourism. On the other hand, it weakens ordinary people from accessing basic healthcare services. This medical ecosystem reflects values that contradict the positioning of Chinese medical teams to Africa, often leading to awkward situations for their members. Meanwhile, the awakening consciousness of African medical independence provides new opportunities for Chinese medical teams to integrate into the development of Africa’s health sector.

Faced with the prevalence of neoliberalism and the awakening of medical independence in Africa, the repositioning of Chinese medical teams is also faced with challenges. How to transition from a demand-responsive approach to a deep cooperative approach embedded in Africa’s medical ecosystem, and how to uphold the original intention of being “guiding and representing China’s expertise”? These are urgent questions that need to be answered by China’s policymakers for its foreign medical aid, and its participation in international public health governance.